Professor Sharon Walker's research from California, which examines how bacteria and other particles found in water stick to surfaces, brought her to the Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research in Sde Boker

by Eitan Crane

Professor Sharon Walker, from the University of California at Riverside smiles at the usual question I ask her, and repeats and confirms for the umpteenth time that the water quality in Israel is excellent and that she drinks tap water without fear. "After all, the scientists and engineers in Israel are among the best in the world in the field of water quality and desalination." This is exactly the reason why she is here, in a sabbatical year as part of the American Fulbright program for the exchange of lecturers and students (Israel's participation in this program is managed by the US-Israel Education Foundation). According to Walker, Israel is one of the four leading countries in the field along with the Netherlands, Sweden and the USA.

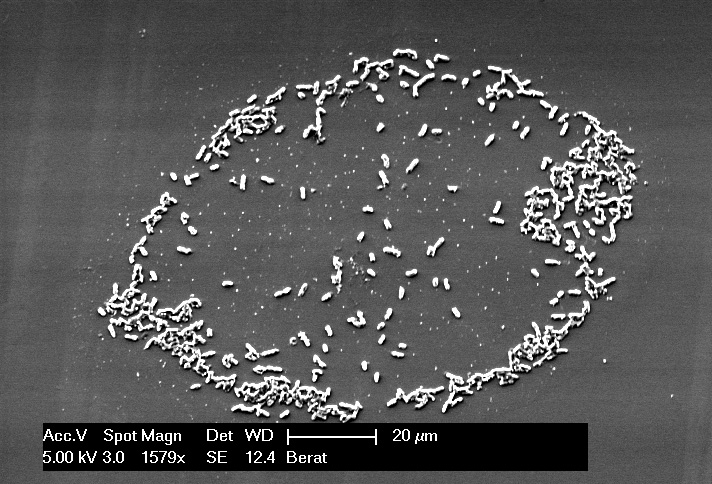

Walker focuses her research on the physical, chemical and biological mechanisms that cause problematic particles in water, natural or man-made, to stick to surfaces, an issue of crucial importance when you want to filter the water and remove these particles. So far, the main focus of her work has been on disease-causing bacteria, such as salmonella and Escherichia coli, which are constantly monitored by the water authorities. The adhesion mechanisms determine whether the particles will remain in the water or stick to the surfaces. The ability of bacteria to stick is affected by many and varied factors: biology gives bacteria a coating of hair-like polymers that allow them to stick. The bacteria are quite sophisticated, says Walker, and sometimes they are able to choose whether to stick or not depending on the nutrients found on the surface - but as it becomes clear later in the conversation, the choice is not always in their hands.

From a physical point of view, it is important to determine the influence of factors such as the speed of the water flow, the degree of mixing and the roughness of the surface. The chemistry of the surface is of course very important, bacteria favor sticking to certain chemical groups, such as oxides, found on the surface of the minerals. The composition of the ions dissolved in the water is also very important. Different concentrations of calcium, sodium, chlorine and other ions contribute to the chemical interactions with the surface. Walker emphasizes that for her it is not important whether a certain variable helps the bacteria to become infected or causes it to be rejected from a surface, what is important is the very understanding of the effect of the various factors, an understanding that will improve our ability to eliminate them.

Designing new materials that allow bacteria to adsorb is the area of activity of several researchers at the Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research, because membranes play a primary role in water desalination. The researchers are interested in preventing as much as possible the adhesion of bacteria to the membranes in order to prevent the formation of a biological plaque that usually clogs them. This activity, which takes place at the Zuckerberg Institute, is one of the examples of the application of the results of Walker's research. Indeed, one of the studies Walker was a partner in in Israel, which has already been published in the prestigious Langmuir journal covering surface research, deals with preventing the adhesion of bacteria using a molecule that adsorbs to the surface, changes their chemical properties and makes them uncharged and hydrophobic. Dr. Moshe Herzberg, Walker's Israeli colleague and her academic host, says that not only does this molecule prevent infection, but it also disrupts the bacteria's ability to sense the quorum and prevents them from forming a plaque.

This article emphasizes the main conclusion arising from Walker's works: the most important factors in bacterial adhesion are not biological factors but rather chemical-physical factors, especially electrostatic forces. The bacteria are covered in protein polymers, explains Walker, which under the chemical conditions of the water are almost always negatively charged. These bacteria will be attracted to positively charged surfaces, and the forces will grow stronger as the salinity of the water increases. In fresh water the stronger forces are actually repulsive forces. This conclusion stands in some contrast to the popular claim that bacteria stick to surfaces to obtain more nutrients. "But sometimes the electrical forces are so strong that they cause bacteria to be infected or rejected just because these are the forces acting. Just like we cling to the face of the earth whether we like it or not," says Walker.

As mentioned, recently Walker began researching new particles, non-biological nanoparticles, whose toxic effects are unknown and the medical community is concerned about. Walker came to the conclusion that the factors influencing the adhesion of such particles are not fundamentally different from the forces acting on bacteria. The reason the research on the subject has only started now, Walker explains, is the constant increase in the concentration of nanoparticles in water due to their introduction into consumer products such as toothpaste, and the growing concern about their effect. And she also says that only recently have the tools developed to allow the study of nanoparticles in water. Walker attaches phosphorescent tags to particles, bacteria or nanoparticles, and observes them under a microscope under different conditions, such as in a flow cell, to quantitatively determine the rate of their attachment to surfaces.

Sharon Walker's research is indeed in the field of pure science, but its practical implications are clear. It works in collaboration with USDA experts at their testing facilities to examine how water quality regulations can be improved. During her stay at Sde Boker, Walker was able to initiate and approve a program for cooperation between Ben Gurion University of the Negev and between the USDA and Riverside University for exchange of researchers.

For Sharon Walker, it is very important to encourage teenagers, especially girls, to study science and engineering. She is active in several nationwide organizations in the US that work to increase the relative share of women in research. Every year, 500-1000 young girls, from first grade to high school, come to the Riverside University campus to break stereotypes and see that engineering is not just a profession for boys. "I'm very concerned that there won't be enough engineers in the future," says Walker. "That's why it's very important to put effort into encouraging girls to learn these subjects." We end the conversation with a question Walker usually challenges young children she meets: "What are the things you did today that did not involve the work of scientists and engineers?"

Dr. Eitan Crane is the scientific-operational editor of Scientific American Israel and head of the culture-science program at Hemda (www.hemda.org.il/culture). The interview took place with the assistance of the Fulbright Foundation.

The Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research was founded in 2002 as part of the Yaakov Blaustein Institute for Desert Research at the Sde Boker Campus of Ben Gurion University of the Negev. The institute brings together various aspects of water research, from groundwater extraction and desalination techniques to studies in environmental hydrology, hydrobiology, hydrochemistry and economics and management of water resources. The institute places special emphasis on the research and development of water sources in arid regions in general and in Israel and the Middle East in particular. The institute also operates a study program in hydrology, water engineering and water resources management to meet the growing demand for professionals in the field.