The preservation project of Albert Einstein's writings allows rare glimpses into all areas of his life - scientific and personal. About the project to preserve Einstein's writings

Issachar Ona Galileo Magazine

At the stationery factory we have to set the date. Often these are not simple tasks - Einstein did not bother to write a date, but contented himself with writing the day of the week

Don't we know everything about Einstein? no and no! In the editing work of his letters, new and interesting and sometimes even amusing facts are revealed. We discover scientific topics that occupied Einstein without us knowing about it. Various letters reveal an unknown face of Einstein the man, and facts we did not know about his life.

After I describe the great project of editing his writings, I will give some examples referring to one year, 1920-1921, an interesting and important year in Einstein's life, when he was 41 years old.

prologue

A few years ago, while I was sitting in the system of Einstein's writings at Caltech in Pasadena, California, and reading his letters, I came across a letter from Berlin sent to his best friend, the physicist Paul Ehrenfest, who lives in Leiden, Holland, and here is a little of it: "I received the 10,000 marks [month Before that, Einstein received the same amount. Ya.A.]. The calculation is thus: the price of the piano [that Einstein bought for Ehrenfest. Ya.] 16,500 marks. Packaging, transport and export license - 239 marks. I have 111 marks left which I will use to buy the violins you asked for..." (February 2.2.1920, XNUMX).

I tried to understand this simple calculation and I failed because it is not correct. I went down to the basement and looked at the original letter, assuming that the typist made a mistake in copying, but no - the mistake was indeed made in the original.

I continued my work with feelings of frustration until I found Ehrenfest's answer (February 8.2.1920, 0). The letter opens with a quote from a British monthly: "We thought that space is straight and Euclid is true and God said: Let there be Einstein, and all the distortion", and continued: "We laughed a lot at your brilliant calculation... Indeed, 'God said, let there be Einstein and all the distortion'". By reading these words I could once again sleep in peace [by the way, you can understand the meaning of the mistake if you omit XNUMX from the large numbers, YA].

This is a small example of the amusing and interesting surprises we discover while editing the articles.

Later I will briefly review the history of the Einstein archive and the enterprise for editing and publishing all his writings.

Einstein Archive (AEA)

Einstein had no interest in keeping copies of his letters. Fortunately for us, many others made sure to keep his letters. Milva, his first wife, kept all his love letters as well as all his other letters to her and their sons. Both Elsa, his second wife, and his stepdaughters, Ilsa and Margot who lived with them, faithfully kept all his letters. So did many friends and colleagues. Notebooks of his notes from courses he studied as well as from courses he himself prepared were also preserved.

The more he became famous, the more attention was paid to the preservation of his writings (including drafts) and his letters.

In 1927, eight years after he gained worldwide fame due to the observations that confirmed the theory of general relativity, Einstein hired a young secretary, who devoted her entire life to the man and his archive. Her name was Helen Dukas: she never married, lived with the Einstein family in their home and became a real member of the family. First lived with them in Berlin, immigrated with them to the United States and lived with them in Princeton. Dukas arranged, filed and organized every letter and every document meticulously and devotedly for 55 years (!) until her death in 1982, i.e. another 27 years after Einstein's death, and thanks to her the wonderful archive exists.

On March 1.3.1925, 1950 (a month before the official opening of the Hebrew University) Einstein wrote his first will. Already in this will he bequeaths all his books and writings to the "Library in Jerusalem". In XNUMX, five years before his death, he made his last will in which he unequivocally bequeathed all his books, writings and all his intellectual assets, including copyrights, to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Undoubtedly, Einstein loved the university (even when he was angry with its leaders) for which he worked so hard (and see the article by Hanoch Gutfreund). In the same will, Einstein appointed Helen Doukas and his lawyer Dr. Otto Natan as the administrators of the estate.

The archive then contained about 40,000 documents. A few months after Ducasse's death, the archive was transferred, under strict guard, from the house in Princeton to the university in Jerusalem: since then it has resided in honor in the basements of the National Library in Givat Ram. However, before the transfer, two complete copies of the entire archive were prepared. One stays at Princeton University and the other travels (see below).

Einstein Writing Factory (EPP)

In 1971, an agreement was signed between the Princeton University Book Press (PUP) and the administrators of the estate, Nathan and Doukas, according to which the publisher receives the editing and publishing rights of all Einstein's writings.

The first volume of the writings appeared in 1987 (!). What happened during the last 16 years? For about ten years, the arguments in the courts continued between Natan and Doukas on the one hand and the editors of the articles, appointed by PUP, on the other. The former demanded the right to active and full intervention in the editing procedures. Their intention in this demand was to exercise censorship: they wanted to block the publication of documents referring to personal (and sometimes even intimate) matters from Einstein's life. The editors, for their part, insisted that the collection of writings include every document that sheds light on Einstein the scientist and Einstein the man. Finally the court ruled in favor of the editors and the editing started.

Particularly difficult is the deciphering of the complicated mathematical formulas from the manuscript. Clarifications are also often required regarding the physical content of the documents

In 1985, when the first volume was ready for printing, something important happened. One of the editors discovered in a random meeting that a large collection of Einstein's letters, including many love letters to Mileva, was kept by a family member. It was clear that the publication of the first volume should be delayed until these letters could be included. It so happened that the volume came out in 1987.

Since then, the work of editing and publishing continues regularly and successfully. In the first years, the editor was based in Boston, the city of physics professor John Stachel (Stachel), who was the editor-in-chief. In 2000, after seven volumes appeared, the editor moved to Caltech in Pasadena, California, where Diana Buchwald, the new editor-in-chief, is professor of the history of science. In the same year, the writer of these lines joined the system in California as a consultant and guest editor.

As mentioned, the system is accompanied by one copy of the archive. Einstein himself liked the place and visited it for several winters while still in Germany. The warm climate, the hospitality and the free and open human atmosphere enchanted him.

Every day more writings are discovered

So even today the archive continues to grow and grow. New documents, many of them important, are discovered almost every day in private collections and various archives around the world. Sometimes, the documents (or their photographs) are donated to the Einstein archive by their owners. Sometimes they are discovered when they are offered for sale in trading houses or at auctions.

About two years ago, a large collection of private letters that Einstein wrote to his family members was published. Einstein's stepdaughter, Margot, donated the collection about 27 years ago, on the condition that it be opened for reading twenty years after her death. She died in 1986. Today, the Einstein archive numbers about 55,000 documents.

So far 10 volumes of Einstein's writings have appeared in print. Volumes 11 and 12 are in print.

The articles are published in chronological order. There are separate volumes for publications and manuscripts (of articles and lectures), on the one hand, and for letters, on the other hand. The 12 volumes contain all the writings up to the year 1921 (inclusive), i.e. up to the age of 42; 34 years left to live. It is estimated that the plant will end with 35 volumes, in about 25 years.

Below is the list of the volumes that appeared (about - articles, m - letters):

Volume 1 - the early years 1879 - 1902; Volume 2 - The years in Switzerland 1900 - 1909 (c); Volume 3 - The years in Switzerland 1909 - 1911 (c); Volume 4 - The years in Switzerland 1912 - 1914 (c); Volume 5 - The years in Switzerland 1902 - 1914 (m); Volume 6 - The years in Berlin 1914 - 1917 (c); Volume 7 - The years in Berlin 1918 - 1921 (c); Volume 8 - The years in Berlin 1914 - 1918 (M); Volume 9 - The years in Berlin 1919 - 1920 (M); Volume 10 - The years in Berlin 1920 (m); Volume 11 - index to volumes 1 - 10; Volume 12 - The years in Berlin 1921 (m).

Another day at the factory

Physicists, historians and technical staff work at the writing factory. What do we do in the factory system? First, the sender of the document and the recipient must be identified with certainty. Second, the date must be set. Often these are not simple tasks - Einstein did not bother to write a date, but contented himself with writing the day of the week.

After that, the documents to be published are selected. Letters with trivial content (such as litigation with a publisher regarding writers' fees) are only mentioned in the "diary" at the end of each volume. We give a physical description of each document (handwritten, typewritten, personally signed, etc.). After that, clarifying and explanatory notes are added, in which a lot of work is invested. Sometimes it takes real research to illuminate a letter or passage in Einstein's paper.

The notes contain information about the writers as well as about personalities mentioned in the letters. A reference is given to other relevant letters as well as to articles or other scientific material related to the topics mentioned in the document. Clarifications are given on the historical background to the letters (here, newspapers from the same dates are used a lot). Reference is often made to documents held in other archives around the world.

We also write comprehensive introductions to groups of documents that all revolve around one central topic (scientific, political or personal), for example: a letter to the young physicist Lisa Meitner dated July 24.7.1921, 17. Meitner is the one who discovered the phenomenon of nuclear fission XNUMX years later.

I myself mainly work on documents with scientific content. Particularly difficult is the deciphering of the complicated mathematical formulas from the manuscript. Clarifications are also often required regarding the physical content of the documents. I enjoy, of course, also reading letters of a personal nature. The documents themselves are published in their original language (usually German). The introductions, titles and all notes are in the English language. A booklet containing the English translations of the documents is attached to each volume.

A year in the life of Einstein

Until 1920-1921 the correspondence with Einstein was relatively little. This year it grew to the point of exploding - a whole volume is not enough for letters

Volumes 10 and 12 contain the correspondence from 1920-1921, one of the most special years in the scientist's life. In 1919 observations confirmed the fact of the curvature of a light beam passing near the sun. The measurements matched Einstein's prediction in the theory of general relativity. From the day the observations were published (in November 1919), Einstein became the most famous scientist in the world. Einstein himself would say that since then a model became a photographer... The results of this transformation in his life were not long in coming.

First, until this year, the correspondence with Einstein was relatively small (about 10 years are included in one volume, on average). Now it has grown to the point of exploding - a whole volume is not enough for one year's letters. The list of authors includes all the great physicists (most of them Nobel laureates, such as Niels Bohr, Max Planck, and the chemist Fritz Haber) as well as philosophers (Cassier, Schlick, Reichenbach), writers (Roman Rollen, Stefan Zweig), statesmen, Zionist leaders, Universities in Europe and the United States and of course - his close and distant friends and family.

Second, from the moment he became famous, Einstein became a central target of anti-Semitic pressure in Germany. A famous conference organized (August 1920) by the "Society for Pure Science" under a seemingly scientific title, against the theory of general relativity took place in the huge hall of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. At this conference, Einstein was accused of creating a nonsensical theory, of plagiarism and of promoting his publication by cheap means of connections with the Jewish press magnates.

Einstein himself was forced to cancel a promise he made to the renowned physicist Arnold Sommerfeld to lecture at the University of Munich, since he learned that anti-Semitic students were plotting riots during his intended visit. This is what his friend wrote to Sommerfeld (September 27.9.1921, XNUMX): "This time I am writing with a heavy heart. Saying 'no' has never been my forte, especially if it's about breaking a promise... I won't come to lecture at your place as I promised. For some time now, my friends have been warning me to keep my distance from this anti-Semitic hornet's nest."

The third result of his worldwide publication, and perhaps the most significant in his life, was the ambition of the leaders of Zionism, led by Chaim Weizman, to recruit him for the benefit of the Zionist cause. Weizmann realized that the best way to obtain cooperation from his side was to use it for the establishment of a Hebrew university in Jerusalem. In this he succeeded, as we have already seen, above and beyond all his expectations. Einstein agreed to accompany Weizmann and other Zionist leaders on a fundraising trip to the United States (which he called "Dollaria") in the months of March-May 1921. It was his first visit to America, and beyond the importance of the visit to the Hebrew University, it was for him "discovering America". He liked the free and friendly atmosphere he found there. This visit paved the way for his migration there a dozen years later.

Trial and error: scientific correspondence

Despite the anti-Semitic attacks, the exhausting trip to America and the heavy load of letters, Einstein did not stop for a moment from deep and disturbing thinking about the open problems of physics. We learn about all of these from the publications he published at that time, but much more from his letters to his distinguished scientific friends. Especially to Anton Lorentz and Paul Ahernfest in the Netherlands, to Arnold Sommerfeld in Munich and Max Born in Frankfurt (and then Göttingen) in Germany. I deal with these letters as the editorial consultant. Here are three surprising examples of three important problems that troubled Einstein - superconductivity, atomic magnetism and quantum theory.

superconductivity

At very low temperatures, certain materials become superconductors, that is, they conduct an electric current without any resistance. In 2007, an article by Tilman Sauer entitled: "Albert Einstein and the early theory of superconductivity" was published. I will start with a quote from the acknowledgments at the end of the article: "This article owes its existence to the discovery of Issachar Una, who discovered passages in the diaries of Paul Ehrenfest..." It was a surprise! We did not know that Einstein was troubled by not understanding this special and amazing phenomenon.

Einstein had to cancel a promise he made to the famous physicist Arnold Sommerfeld to lecture at the University of Munich, because he learned that anti-Semitic students were plotting riots during his visit

By chance, while looking through Ahernfest's diaries (short entries in scrawled handwriting, intended only for himself) I found a note: "From a letter of Einstein 9.12.1920...". When I asked the old editors where this letter Ehrenfest quotes from, it turned out that it was not known at all.

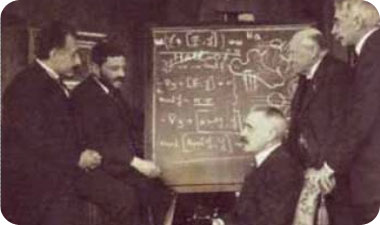

Detective work led to a draft of the letter, in Einstein's handwriting, on the back of a letter addressed to him. The same formulas quoted in Ehrenfest's diary and appearing in the draft are also seen, amazingly, in a well-known photograph (from October 1920) in which Einstein is seen in a meeting with the great physicists specializing in magnetism, and in which he also discovers superconductivity (in 1911, in mercury cooled in liquid helium) Kamerlingh Onnes ), in Leiden in the Netherlands. In the photo, the experts are seen standing in front of a black board with the formulas on it.

In his letter to Ehrenfest, and probably also at the same meeting in Leiden, Einstein proposed a new experiment to clarify the nature of the phenomenon. He failed to explain superconductivity. Like him, many good ones failed in the following decades. The quantum explanation was finally given by three physicists - Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer (Bardeen, Cooper, Schrieffer) in 1956, a year after Einstein's death and 45 years after the discovery of the phenomenon. The three won the Nobel Prize for it.

Atomic magnetism

A few years before, Einstein calculated the relationship between the magnetic moment of an atom and its angular momentum, on the simple and classic assumption that the magnetic moment derives from the ampere current of the movement of the electrons around the nucleus of the atom. He found the formula: M=(e/2mc)J. (M – magnetic moment, e – electron charge, m – electron mass, c – speed of light, J – angular momentum). And in short: M=gJ.

The constant g, which gives the ratio between the magnetic moment and the angular momentum, is known as the "gyromagnetic ratio". Einstein also designed an experiment to measure g and performed it together with the Dutch physicist Wunder de Haas. They found good numerical agreement with the calculated formula. However, measurements made at the time in the United States indicated a double value of its own for g (ie: g=e/mc).

To Einstein's credit, he actually believed the experiments of the Americans, even though they contradicted his own measurements. In correspondence from the end of 1920 and the beginning of 1921 with Sommerfeld, he expresses his opinion that there is a very deep reason for the gap between his theoretical calculations and the Americans' measurements. In response to Sommerfeld's and his assistants' attempts to explain the gap, he writes (July 13.7.1921, XNUMX): "I don't believe your explanations... Satanism is deeper." The explanation was discovered only five years later with the discovery of the spin of the electron and the combination of relativity with quantum theory by the British physicist Paul Dirac.

Experiments to understand quantum theory

Einstein himself admits in many articles and letters that understanding the essence of light answers him more than any other problem he dealt with

Einstein was the first person to believe in the existence of light particles (photons), already in 1905. On the other hand, most of the physicists of his generation, including the great ones like Niels Bohr and Max Planck, did not believe in it. It took them about 20 more years to be convinced of the correctness of the quantum idea of light - the behavior of light as an electromagnetic wave, according to Maxwell's theory, made it very difficult to understand its quantum nature.

Einstein himself admits in many articles and letters that understanding the essence of light troubled him more than any other problem he dealt with, and it indeed continued to trouble and answer him until the end of his days. In 1921 he devised and proposed two different experiments that were supposed to decide between Maxwell's wave theory and quantum theory - the description of light as a collection of particles (photons). In a letter to Sommerfeld (4.1.1921) he writes: "I am terribly curious to know what the result will be [of the first experiment he proposed to perform. Ya.A.]. I have to admit frankly - I don't know what I prefer. Alas, the conflict between energy particles and a wave field is still completely unresolved."

Today we know that quantum theory accepts duality as an existing fact. The question "Is light a wave or a barrage of particles?" is illegal! Einstein writes to his four physicist friends about the experiments he proposes and is even about to perform. Ehrenfest, and even more so - Lorenz, try to make him wrong. After all, he himself, in oral conversations, has already come to terms with the duality.

This is how Lorenz writes to Einstein (November 13.11.1921, XNUMX): "It was you who explained to me that a single radiation process [in which one photon is emitted. Ya.] consists of an extremely weak wave, which provides the probabilistic background [for the discovery of the photon. Ya.A.]. This wave is subject to all the classical wave laws [manifested in the phenomena of diffraction, interference, etc. Ya.] But only one particle will be detected. After the single process repeats and occurs a large number of times, the image of the interference (or any other wave phenomenon) will be revealed statistically."

Note, Lorenz quotes Einstein: the year is 1921. The quoted idea is very similar to the quantum theory of Schrödinger, who came up with the idea of the wave function of the single electron, and the probabilistic interpretation given to it by Max Born. But these were published for the first time from 1925 onwards - Einstein was therefore a few years ahead of the forefathers of quantum mechanics.

A few months later, Lorenz gave a series of lectures at Caltech in which he repeated Einstein's ideas, but Lorenz emphasized with his wonderful integrity: "Let me present to you ideas regarding the apparent contradiction between the wave phenomena of light, on the one hand, and the hypothesis of the existence of light particles, on the other hand. I will go ahead and say that the credit for everything that is believed in these ideas goes to Einstein. But, since they are known to me only through conversations and rumors, I take full responsibility for everything that is unsatisfactory about them."

Non-scientific correspondence

I will conclude with two amusing examples of other correspondences.

The "Scientific American" award - in a letter to Einstein, Lorenz writes (September 10.9.1920, 5000): "Have you read that it is now possible to make money from the theory of relativity?". Lorenz refers to an ad published in the popular science newspaper "Scientific American". In the ad, the newspaper announces a contest and a prize of XNUMX dollars [a huge sum in those days. Ya.] to be given to the best paper on relativity. "I am sure that the judges will be wise enough to choose an article from your pen if you send them such an article," writes Lorenz.

Einstein answers: "I already learned about the competition directly from the donor of the prize and I immediately decided that I would not be involved in this. I don't like dancing around the golden calf. Besides, my talents are so poor…”

The Alexander Moskovsky case - in the same year (1921) the first biography of Albert Einstein (who was only 42 years old!) was about to be published. Its author, Alexander Moskovsky, was a Jewish journalist who immigrated to Berlin from Eastern Europe, and was also a smart and talented person who was successful as a writer of satires and humorous columns in popular German newspapers. He used to visit Einstein at his house and he liked it.

One day, in October 1920, an ad was published about a book by Moskovsky about to be published: "Einstein - a look into the world of his ideas". The news raised the community of scientists in Einstein's circle to its feet, who received an upset letter from Hedi Born (Max Born's wife): "You must immediately deny by registered letter the permission you gave him to publish the book. This book must not appear in Germany or any other country."

Max Born and his wife and certainly other colleagues also witnessed a terrible humiliation: a Jewish journalist from Eastern Europe, who specializes in Jewish jokes and cheap anecdotes, will publish a book about the great scientist?! After all, this will play right into the hands of the anti-Semites, especially the physicists among them, who have long claimed that Einstein is raising cheap advertising. The assimilating Jews born in Germany could not bear the idea that this "type" would publish a book about their hero.

"Now I understand," adds Bourne, "why he was pushed towards you. He smelled the gold mine he was about to find." Einstein replies in a short letter to Max Born, that even if his wife exaggerated her judgment about Moskovsky, there is truth in her words and he did send a registered letter as she suggested. In response, he received an emotional letter from Berta Moskovsky, Alexander's wife, in which she laments bitterly: "On that terrible Friday, when your letter was received...", she complains, "There is a signed contract with the publisher and the printing is almost complete..." To add fuel to the fire, the Burners suggested heading home - Trial and request a restraining order on the publication of the book. In contrast, the Dutch Lorenz and Ehrenfest advised against going to court, an act that would only intensify the scandal and make it headlines.

In the end, the book was published without any scandals, and as Einstein writes: "The sky did not fall", and in another letter: "I still love Moskovsky more than Lennard and Wynn" [well-known physicists, Nobel laureates, and vicious anti-Semites. Ya.A.].

EPP

epilogue

One morning, sitting in the Einstein writing system in Pasadena, the phone rings. The speaker introduces himself: "I'm Steve Moskowski, Alexander's grandson..." He is interested in the correspondence between his grandfather and Einstein. By the way, an amusing correspondence, which even includes a poem that Einstein wrote for Moskovsky. After a long conversation it turns out that we are old acquaintances: Steve is a nuclear physicist and a professor at the University of Los Angeles.

His father, who was a lawyer in Berlin, converted his religion and the religion of his children to Christianity. In 1938, of course, they had to flee Germany. With Einstein's help they came to the United States. Steve was a closed and lonely boy, and his worried mother went to Princeton to consult with Einstein, who reassured him: "Don't worry, let him be alone as he wishes." Indeed, the boy grew up to become a world-renowned physicist. Happy ending: Steve's children returned to Judaism, repented and lead an ultra-Orthodox, Hasidic lifestyle in an ultra-orthodox community in England - the vicissitudes of the Jewish people are embodied in the story of one family. "When I visit my children," says Steve, "I am a good Jew."

Since that scandal surrounding the first biography, dozens of biographies about Einstein have been published in many languages. The biographies, most of which were published after his death, contain a lot of interesting information about his achievements in science, his Zionist and political activities, and even gossip about his private life. But as was made clear, we are still far from knowing everything about him today, and there is no doubt that new discoveries await us.

Professor Issachar Ona, Rakah Institute of Physics, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Guest Editor in the Einstein Writings System and Chairman of the Academic Council of "Magnes" Publishing

On the same subject:

6 תגובות

The program about Einstein was quite interesting, but the episode about the brain was nothing... A lot of technological and scientific innovations related to the topic were not presented at all, and on the other hand, a considerable part of the program was dedicated to pseudo science such as telepaths and such, the topic was presented as if it had already been confirmed by scientific experiments... Shame on the channel.

Is it possible to arrange that links in messages always open in a separate window? It is much more convenient and accepted by default on most sites I know (also on YNet) It is very inconvenient that the link opens in the same window and the original article is lost.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —>

1. A short and interesting interview with Idan Segev, brain researcher and representing Israel in the amazing project in Switzerland -

http://www.youtube.com/watch?gl=US&v=Bz5IUaRr8No

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —>

2. A fascinating lecture by the project manager -

http://neuroinformatics2008.org/congress-movies/Henry%20Markram.flv/view

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —>

3. Idan Segev in a lecture from the same conference -

http://neuroinformatics2008.org/congress-movies/Idan%20Segev.flv/view

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —>

4. A fascinating PDF document about the project, from the website of the "Odysseus" magazine, click the right button on the link and choose "Save as..."

http://www.odyssey.org.il/pdf/עידן%20שגב-מסע%20מודרני%20אל%20נבכי%20המוח.pdf

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —>

5. An article from R-T-K (and updated) in English about the project -

part 1 -

http://seedmagazine.com/content/article/out_of_the_blue/?page=2

part 2 -

http://seedmagazine.com/content/article/out_of_the_blue/P2

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —>

6. Seeing through the mind, from Amnon Carmel's blog -

http://www.tapuz.co.il/blog/ViewEntry.asp?EntryId=1399918

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —>

7. Hebrew: The singularity is near! The future is fast approaching us -

http://www.tapuz.co.il/blog/ViewEntry.asp?EntryId=1065939

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —>

8. Another fascinating article in Hebrew -

http://www.themedical.co.il/Article.aspx?itemID=1868

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —>

9 - New PDF document, right click on the link and "Save as..." -

http://www.biomedicalcomputationreview.org/5/2/7.pdf

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

For anyone interested, today (Friday) on the History Channel there are two fascinating programs (like most of the episodes on this channel), first of all at 22:40 PM a program entitled "Einstein" -

"A review of the work of the inventor of the theory of relativity, Albert Einstein, with the frame story taking place between 2 important solar eclipses. On 29/5/1919, a solar eclipse occurred in which scientists photographed a star that was supposed to be hidden by the sun, which proved his theory.

And immediately afterwards at 00:15 an even more fascinating program on the subject of the human brain -

"Scientists are only now beginning to understand the most complex machine in the universe: the human brain. We will embark on a fascinating evolutionary journey into the study of the brain. Modern analysis techniques have enabled us in the last 5 years to know more about the brain than in the 100 years before that.

For those who miss today, there is another chance tomorrow at noon, only in reverse order -

14:00 – The human brain

15:30 – Einstein

Hope it will be as good as it sounds 🙂

😳 💡 :oops: It's important to preserve more than ever: he is first and foremost the firstborn of 'true' science both in 'free' and in 'human innocence' - in a playful and good Jewish heart.

Abby, it seems to me that you published an article very similar to this one before.