Ariel Eisenhandler, Israel Astronomical Society

The alluring and amazing fantasy comes, sooner or later, to almost everyone: what if everything we know, the entire universe, is nothing more than a speck of dust on someone's shoulder? Of course, astronomers don't take this idea seriously, but many cosmologists take seriously a more scientific question: Are there other universes?

At first glance you can't help but wonder how anyone has the audacity to ask such a question: we barely understand this universe, so now we're wondering about others? Believe it or not but theorists have an answer and the answer is probably yes, there are other universes!

To understand why we must return to the big bang, that mysterious explosion that is considered the mother of all explosions, which astronomers believe gave birth to our universe. According to the theory one moment there was nothing. A moment later our universe sprang into existence. Nature seems to have succeeded in the operation of obtaining something, or rather everything, in vain.

As fanciful as it sounds, this follows directly from the theory of quantum mechanics (a set of mathematical laws that describe how our universe works at the smallest scale, inside the atoms). According to this theory, matter and energy can appear spontaneously from the void in space thanks to quantum fluctuations (instabilities), a kind of hiccup in the energy field that fills the universe.

Cosmologists claim that the quantum fluctuations caused the big bang and they can happen anywhere and at any time, and if our universe was born from quantum fluctuations then it is possible that other quantum fluctuations resulted in the creation of other universes.

There is a reason why a number of theorists want the existence of other universes: they believe it is the only way to explain the existence of our universe, whose physical laws allow the existence of life. According to the entropic principle, there are probably an infinite number of universes, each with its own set of physical laws, and one of them happened to be ours. Adherents of the entropic principle claim that it is easier to believe in this than in a single world that directs a subtle direction towards our existence. But there is a problem: if these universes do exist, there is no way we can discover them.

Of course, as astronomer Chris Impey of the University of Arizona points out, there are parts of our universe we can't see because the light from those distant worlds hasn't had enough time to reach us. "We know that our physical universe is, in reality, enormously larger than the visible universe," Impey says. This does not mean that he is ready to accept the idea of the existence of other universes. First of all, says Impi, cosmologists do not really understand the nature of quantum fluctuations, "because we still do not have a quantum theory of gravity", this means that the idea of multiple fluctuations and multiple universes is completely imaginary (theoretical).

Other astronomers are even more vigorous in their opposition to the idea.

"This is not a testable idea," says Paul Steinhardt of Princeton University. Because the different universes won't be able to discover each other, Paul says, "you can't really prove their existence or non-existence." When you talk about multiple universes you are no longer talking about science, says Steinhardt. "In my opinion, this is metaphysics (abstract matters)."

But not everyone rejects the idea of multiple universes outright. Virginia Trimble (Virginia Trimble), from the University of California, tends to accept the idea. "I find the idea cool, just as much as I think it would be cool with reincarnation." Not exactly a scientific confirmation that rings well.

But Andreas Albrecht, a cosmologist at the University of California, says that the question is not open to debate. why? Because you can't argue with quantum mechanics. "As far as we can tell," says Ulbrecht, "this is the basic language in which nature speaks. Nature does not answer questions with certainty; He answers questions by giving probabilities", and in quantum mechanics, "there is the possibility that almost everything happens." Including other universes, and if the cosmologists feel pangs of conscience because of the matter then they have no choice. "It turns out this way according to the math," explains Ulbrecht, "this was forced upon us."

"Quantum mechanics will not give up the other alternatives by itself," says Ulbrecht. And we really don't know what to do about it. On the one hand it sounds completely metaphysical. On the other hand, this is all we have to work with right now."

So how would Ulbrecht answer the questions of Impey, Steinhardt and others who challenge the idea of multiple universes? ” I would tell them: 'Your instincts are good but do something with them. Give me a theory that doesn't have multiple universes.' They will be stuck.”

This does not mean that Ulbrecht agrees with the followers of the entropic idea. All the "fine balances", which they believe are too good to be true, are true of life as we know it. About those followers Ulbrecht says: "They have no idea about life. They don't know what it takes for there to be life in the universe. There could be life forms out there that we haven't thought of yet! It's completely stupid."

There is no shortage of publishing scientific papers, articles and books on the theory of entropy, including some written by experienced cosmologists. "..and good science is also involved in these studies, if you take out everything related to the entropic principle," says Ulbrecht.

"People enter these studies because they are intrigued and because there are real scientific issues to be addressed. Then they say, 'Oh, that looks familiar. I should call it entropy,' and they start using all these buzzwords, but they alienate a lot of the scientific community when they do that. It's a form of negligence."

” Science is not being careless, but it is difficult because we are human. This is an example of our humanity creeping in and interfering with absolute rationality. I think that over time it will go and improve to a great extent."

"In the end we may realize that there are a number of other universes, but it won't be in the way the entropy guys want... There's a big difference between the diversity the entropy guys want and the existence of a few more universes around."

Can other universes be discovered?

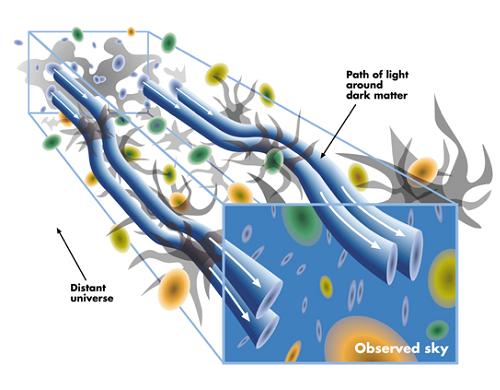

But if these other universes do exist, are we destined to never discover them? A number of theorists postulate that gravitational energy from those universes could leak into our universe and we may one day figure out how to detect it, but even very open-minded cosmologists say that the odds are slim at best.

"This is also a pure assumption," says Impi. "Perhaps it is a reasonable assumption, but it is an assumption that is similar in its characteristics to the assumption of someone like Kip Thorne about wormholes, time travel, white holes and black holes. This is a very cautious assumption given by a highly trained physics theorist who knows the limits of the current theory."

It wouldn't be the first time that a crazy idea turns out to be true.

A little over a century ago, in the second half of the 19th century, says Ulbrecht, most scientists did not accept the idea that matter is made up of atoms - an idea that was supported not only by direct observation but also by the arguments based on theories of temperature, heat and viscosity .

"The atomic theory had wonderful things to say about it, and it seems to have given a consistent and unified picture," says Ulbrecht, but "most physicists at that time did not really believe in the existence of atoms; They thought it was idle talk, like fortune-telling."

Ulbrecht points out that like quantum mechanics, atomic theory was a construct that went far beyond what people could see 100 years ago, and if embracing crazy ideas like other universes is a challenge for current scientists, then that comes with the territory.

"So far everything we have done to try to understand the universe has taken us out of our shell, so to speak, and made us think about things that are far beyond what we see, and far beyond what we will see in the near future. So we're just stuck with it… unfortunately, it's part of the nature of always being the pioneer of what we understand.”

For information on the National Science Foundation (NSF) website

The website of the Israeli Astronomical Society