The relaunch of the space shuttle will cut a series of important projects of the American space agency. The main victims: spacecraft that observe the sun and spacecraft that study the weather in space

Mark Alpert, Scientific American

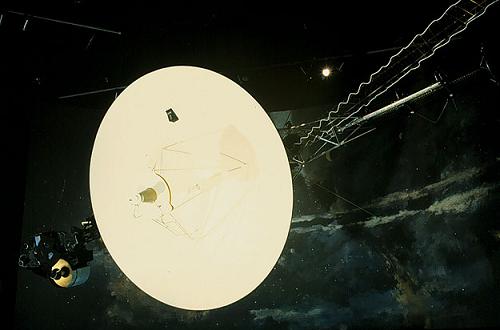

The Voyager 1 spacecraft (pictured), located at a distance of 14 billion km from the Sun, is further from Earth than any other man-made object, but it is still within range of the ax wielded over the budget of the American space agency, NASA. The agency's new focus, now aimed at manned research, including the resumption of shuttle flights

The spacewalk, which took place in July 2005, attracts funds intended for unmanned spacecraft that explore the Earth, the Sun and other regions of the Solar System.

Forty percent of NASA's $16.5 billion budget is dedicated to the shuttle and the International Space Station. In addition, NASA allocated 753 million dollars for the design of the new Crew Exploration Vehicle, which will take the astronauts into orbit after the shuttles finish their missions in 2010.

To help fund that effort, the agency has proposed significantly cutting the budget of the Earth and Solar Systems Department, which operates Voyager 1 and 2 and a dozen other spacecraft that have completed their primary missions but continue to yield valuable data. The department, which was ordered to cut 20 out of the 75 million dollars in its budget, will consider its steps in the fall of 2005 and decide which spacecraft it must sacrifice.

May be affected: observation of the sun, weather

Among the possible victims are spacecraft that observe the Sun (such as Ulysses and TRACE) and spacecraft that study the "weather" in space around the Earth (such as Polar, FAST, Geotail and Wind). In order to continue operating the spacecraft until the expected inspection, NASA rejected funding for research proposals designed to analyze the data coming from these spacecraft.

The uproar over the Voyager missions is the loudest. The twin spacecraft, launched in 1977, have explored the planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune and are capable of continuing to operate until they have consumed their entire stockpile of plutonium fuel in about 15 years. In 2002, Voyager 1 reported a sharp increase in the particle count, which suggests that it may have crossed the region in space known as the termination shock - the turbulent boundary where the solar wind begins to swirl in interstellar space.

The spacecraft recently picked up new signs of turbulence and the scientists of the project, which costs $4.2 million a year, claim that canceling it is an act of folly. "It's like Columbus, once he spotted the continent, would say, 'OK, let's go back,'" says Stamatios Krimigis, principal investigator specializing in Voyager-1's low-energy particle sensor.

Meteorologists and geologists are also arming themselves for the fight. In April 2005, a report by the American Research Council (NRC) stated that NASA's array of Earth observation satellites "is in danger of collapsing." Six missions were canceled, reduced or postponed. In some cases, the cuts threaten to create gaps in the recording of the environmental data that NASA has worked on collecting for decades. For example, the agency originally planned to launch a follow-up mission to replace the aging Landsat-7 satellite, which tracks everything from deforestation in the tropics to the collapse of the Antarctic ice sheet.

The satellites are already starting to fake

But now NASA intends to build only Landsat's cameras and place them on weather satellites of the US National Weather Service (NOAA). The delay will undoubtedly cause a data gap: Landsat-7, launched in 1999, is already beginning to "fake" and NOAA's first satellite will not be launched until 2009. Moreover, researchers claim that the heavy NOAA satellites will be prone to vibrations that will destroy the image quality of Landsat's sensors .

Budget pressures are also slowing the effort to understand climate change. The future of the Glory mission, which was designed to measure for the first time global soot and dust and determine their impact on the climate, is now in question. The instruments of this mission may also be mounted on one of the NOAA satellites. "It's wrong to put all these things aside," says Richard A. Anthes, a hurricane expert who co-chaired the NRC panel of experts. "We cannot afford not to follow the Earth."

The scientific community hopes that NASA's new administrator, Mike Griffin, will reverse some of these cuts to research missions. Before taking the top job at NASA, Griffin headed the Space Department at Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory. Krimigis, who held the position before Griffin, believes in his colleague. "I know Griffin, I interviewed him for the position," Krimigis says. "I'm pretty sure he'll do the right thing."