Many human species have inhabited the earth, but our species is the only one to inhabit the entire planet. A new hypothesis explains why of all the human species that lived on earth, only Homo sapiens was able to colonize the entire planet / Curtis V. Marian, Scientific American

For a long time, scientists tried to answer the question of why only our species was able to spread over such vast areas.

According to a new hypothesis, two things that distinguish Homo sapiens led to its domination of the world: a genetic tendency to cooperate with individuals who are not relatives and the use of advanced weapons that can be sent from a distance.

Less than 70,000 years ago, our species, Homo sapiens, left Africa and began its vigorous spread across the planet. Other human species established themselves in Europe and Asia, but only the ancestors of Homo sapiens managed to dominate all major continents and many island chains. Their spread was no ordinary event. Everywhere they went there were huge ecological changes. The earlier human species they encountered became extinct, as did a vast number of animal species. It was the most significant migration event in the history of our planet.

For a long time paleo-anthropologists debated among themselves why only modern man was able to spread himself and dominate the world and how he did it. Some experts argue that the development of a larger and more sophisticated brain allowed our ancestors to invade new territories and face the unfamiliar challenges that presented themselves there. Other experts argue that new technology drove the spread of our species out of Africa by allowing modern humans to hunt prey, and dispose of enemies, with unprecedented efficiency. A third scenario is that climate change weakened the Neanderthal population and other primitive human species that settled in territories outside of Africa and allowed modern humans to overcome them and take over their territories. However, not one of these hypotheses provides an overall theory that can explain the full achievement of Homo sapiens. Indeed, these theories were proposed as explanations for the evidence of Homo sapiens activity in certain areas, such as Western Europe. But this fragmented and unsystematic approach to studying the settlement of Homo sapiens on Earth misled the scientists. The widespread distribution of man was a single event that occurred in several stages, and therefore must be studied as a single subject.

Excavations I have conducted over the last 16 years at Pinnacle Point on the southern coast of South Africa as well as theoretical advances in the biological and social sciences have recently led me to formulate an alternative scenario that explains how Homo sapiens conquered the Earth. In my opinion, the migration happened when our species developed a new social behavior: a genetic tendency to cooperate with non-relative individuals. The combination of this connectivity and the advanced cognitive abilities of our ancestors allowed them to quickly adapt to new environments. He also fostered innovation that led to the development of a technology that changed the rules of the game: advanced weaponry that could be launched. Thus equipped, our ancestors left Africa, ready to subjugate the entire world to their will.

Desire to undress

To appreciate how unusual the settlement of the earth by Homo sapiens was, we must scroll back about 200,000 years to the dawn of the appearance of our species in Africa. For tens of thousands of years these anatomically modern people, who looked like us, remained within the domain of their native continent. About 100,000 years ago, one group went on a short raid in the Middle East, but apparently did not manage to last. These people needed some advantage that they did not yet have. After less than 70,000 years a small founding population broke out of Africa and began a more successful journey to new territories. As these humans spread into Eurasia they encountered related human species: Neanderthal man in Western Europe and details of the recently discovered Denisovan human lineage in Asia. Shortly after the invasion of modern man, the ancient humans became extinct, but some of their DNA remains in humans living today due to occasional pairings between the groups.

When modern people arrived in South Asia, they found themselves facing what seemed like an endless sea with no land. But they continued to advance fearlessly. Like us, these people could yearn and strive for the discovery and conquest of new territories, so they built vessels suitable for the ocean, crossed the sea and reached the shores of Australia at least 45,000 years ago. Homo sapiens was the first human species to arrive in this part of the world, and it quickly filled the continent, running across it with spear throwers and with fire. Many of the large and strange marsupials that dominated the Australian territories at the time became extinct. About 40,000 years ago, the pioneers found a land bridge and made their way to Tasmania, but the sultry waters of the southernmost oceans prevented them from crossing the Antarctic.

On the other side of the equator, a population of Homo sapiens migrated towards the northeast, penetrated into Siberia, crossed territories and circled the North Pole. For a while ice on land and sea prevented them from reaching America. The exact time when they finally moved to the New World is a subject of bitter debate among scientists, but researchers agree that about 14,000 years ago they overcame the obstacles and raided the continent, where until then the wild animals had not met human hunters. In just a few thousand years they reached the southernmost tip of South America, exterminating along the way a huge amount of New World Ice Age animals, such as mastodons and giant sloths.

Madagascar and many islands in the Pacific remained uninhabited for another 10,000 years, then in a last ditch effort seafarers discovered and settled these places as well. As in the other places where Homo sapiens established themselves, these islands suffered the harsh hand of human occupation: burning habitats, exterminating species and reshaping the environment for the purposes of our ancestors. The settlement of Antarctica waited until the industrial age.

Teamwork

Well, how did Homo sapiens do it? How, after tens of thousands of years of being confined to their home continent, did our ancestors break out and take over not only the areas where the human species that preceded them settled, but also the entire world? A successful theory that will explain the diaspora must include two things: it must explain why the process happened at the time it did and not before and also provide a mechanism for rapid movement across land and sea that requires the ability to quickly adapt to new environments and replace any ancestral species found in them. I believe that the appearance of the features that made us incomparable collaborators on the one hand and cruel competitors on the other hand best explains the surprising rise of Homo sapiens to the position that dominates the world. The modern man had these qualities, which could not be stopped in Eden, while the Neanderthal man and the rest of our extinct cousins did not. I think it was the last major addition to the set of traits that made up what the University of Arizona anthropologist Kim Hill called "human uniqueness."

We modern humans cooperate to an extraordinary degree. We join together in a complex and wonderfully coordinated group activity with people who are not leftovers and even with complete strangers. Sarah Balfer Hardy from the University of California at Davis wrote in her book "Mothers and Others", published in 2009, that it is unthinkable for a group of several hundred chimpanzees to stand in line, get on a plane and sit completely passive for hours, then leave like robots that have received a signal: they are They will fight each other non-stop. But our cooperation works both ways. The same species that will leap to defend a beaten stranger will shoot them together with individuals that are not close to fighting another group without a shadow of mercy. Many of my colleagues think like me that the tendency to cooperate, which I call super-sociability, is not a learned trait but a genetic trait found only in Homo sapiens. In other animals such glimmers can sometimes be seen, however, the feature found in modern man is fundamentally different.

The question of how we got a genetic predisposition to such an extreme learning of cooperation is a tricky question. But mathematical models of social development have yielded some valuable clues. Sam Bowles, an economist at the Santa Fe Institute, showed that one of the best conditions that can encourage the formation of genetic supersociability is, paradoxically, conflict between groups. Groups with a higher proportion of sociable people will work together more effectively and thus defeat the others and pass the genes responsible for this behavior to the next generation. The result is the spread of super-sociability. The work of biologist Pete Richerson of the University of California, Davis, and anthropologist Rob Boyd of the University of Arizona shows that such behavior spreads best when it begins in a subpopulation, when competition between groups is intense, and when the size of the population as a whole is small, such as the original population of Homo sapiens in Africa, all modern humans They are her descendants.

Hunter-gatherers tend to live in groups of about 25 individuals, marry outside the group and group into "tribes" united through pairings, exchange of gifts and shared language and tradition. Sometimes they also fight other tribes. However, in doing so they take great risks, which raises the question of what prompts this willingness to enter into a dangerous struggle.

Insights into the question of when to fight came from the classic "economic defense" theory, developed in 1964 by Jerram Brown, a researcher at the University at Albany, to explain variation in aggression in birds. Brown claims that individuals act aggressively to achieve certain goals that will maximize their survival and reproduction. Natural selection will favor fighting when it helps accomplish these goals. One important goal for all creatures is to secure the food supply, so natural selection will promote aggressive behavior if it protects the food supply. If it is not possible to protect the food or the price of guarding is too high, aggressive behavior is not beneficial.

The combination of weapons that can be thrown into supersociety gave birth to a new and wonderful creature

In a classic article from 1978, Rada Dyson-Hudson and Eric Alden Smith, then researchers at Cornell University, applied economic protection to humans living in small societies. In their work they showed that protecting resources makes sense when resources are abundant and their supply is regular. I would add that the resources in question must be necessary for the survival of the creature. No creature will protect a resource that is not necessary for it. This principle is still true today: ethnic groups and nation-states fight brutally over reliable and valuable resources that are abundant, such as oil, water and productive agricultural land. From this territorial theory it is implied that the environments that foster conflicts between groups and the cooperative behavior that enables such war were not universal in the early days of Homo sapiens. They were limited to places where quality resources were available in abundance. In Africa, land resources are generally scarce and unpredictable, which explains the finding that most hunter-gatherers studied there did not waste time and energy on border defense. But even this rule has exceptions. Some beaches have areas covered with shellfish, which served as rich, abundant and readily available food. Ethnographic and archaeological records of hunter-gatherer wars around the world show that the most intense conflicts were between groups that used coastal resources, such as the Pacific coast of North America.

When did humans adopt abundant and readily available food sources? For millions of years, our ancestors subsisted by searching for terrestrial plants and animals that served as their food, and sometimes, when the opportunity arose, they also ate animals in rivers and lakes. All these foods were scarce and most of them unexpected. For this reason our ancient ancestors had to live in small groups far from each other and wander constantly in search of the next meal. As human consciousness became more complex, one of the population groups learned to eat shellfish and subsist on them in coastal areas. My team's excavations at Pinnacle Point sites show that this change began 160,000 years ago on the east coast of Africa. There, for the first time in human history, people made it their goal to locate near abundant, readily available, and highly valuable food sources, a development that brought about important social change.

Genetic and archaeological evidence shows that the Homo sapiens population shrank shortly after its formation due to a global cooling that began about 195,000 years ago and lasted until 125,000 years ago. Seaside environments served as a nutritional refuge for Homo sapiens during the difficult periods of the glacial cycles where it was difficult to find edible plants and animals that were essential for the survival of our species in the ecosystems inside the continent. The food sources on the seashores provided a reason for the war. Experiments on the southern coast of Africa conducted recently by Jean de Wink of the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in South Africa show that a mollusk-covered surface can be an unusually abundant food source, providing up to 4,500 calories per hour of foraging. My hypothesis is that the food on the beaches was an abundant, available and valuable resource. As such, it evoked intensified territoriality among humans, and such protection of living areas caused struggles between groups. This routine war between groups provided conditions for selecting social behavior within groups - teamwork to protect the shellfish grounds and thus maintain exclusive access to this valuable resource - which eventually spread to the entire population.

the weapons

Acquiring the ability to act in groups of unrelated individuals, Homo sapiens became an unstoppable force. But, I suspect, a new technology was required to achieve full conquest capability: a weapon that could be launched from a distance. This invention required a lot of time. Technologies are built on accumulated experiments and knowledge, and they become more and more complex. Thus, one must assume, a weapon that can be launched also developed: from a pointed stick, to a spear that is thrown by hand, to a throwing spear that has a kind of lever to achieve greater speed (atlatl), to a bow and arrow and finally to all the wild inventions of our time for launching deadly tools.

With each new development the technology becomes more deadly. Simple wooden spears with pointed ends tend to cause stab wounds, but such an injury is limited in its impact because it does not cause rapid bleeding of the animal. Connecting a pointed stone to the spear aggravated the injury. This refinement requires several connection methods, but first of all the stone must be sharpened to a pointy point so that it can penetrate the animal's body, and its base must be shaped to allow it to be connected to the spear. Then methods are required to secure the connection of the pointed stone to the shaft of the spear - using glue or binding materials. Jane Wilkins from the University of Cape Town in South Africa and her colleagues have shown that stone tools found at a site called Kathu Pan 1 in South Africa were used as spear tips about 500,000 years ago.

The ancient age of the find from Cathu Pan 1 suggests that it is the handiwork of the last common ancestor of Neanderthal and modern man, and remains later than 200,000 years ago show, as expected, that the descendants of both species continued to make this type of tools. This shared technology means that at one time there was a balance between the powers of Neanderthal man and early Homo sapiens.

Experts agree that the appearance of tiny stone tools in the archaeological record indicates the appearance of throwing methods that require light-weight projectiles and an understanding of ballistics. Such tools are too small to be held in the hand, and had to be mounted in slots cut into bone or wood to create weapons that could be launched from a distance at great speed. The oldest example of this method of creating tiny pointed stones came from Pinnacle point itself. There, in a stone shelter known as PP5-6, my team found evidence of a long period of human activity. Geochronologist Zenovia Jacobs from the University of Wollongong in Australia determined by using a method of luminescence based on optical excitation that the archaeological sequence in PP5-6 began 90,000 years ago and continued until 50,000 years ago. The tiny stone tools on the site that were used for hunting are from about 71,000 years ago.

The timing suggests that climate change accelerated the invention of the new technology. 71,000 years ago the inhabitants of PP5-6 made large stone points and blades from a rock called quartzite. So, as team member Erich Fischer of Arizona State showed, the shoreline was close to Pinnacle point. The reconstruction of climatic-environmental history by Mira Bar-Matthews from the Israel Geological Survey and Christine Brown, a post-doctoral student at Arizona State University, shows that the conditions then were similar to those prevailing today: intense winter rains and bushy vegetation. But about 74,000 years ago, the world's climate began to cool and glaciers formed. The sea level dropped and exposed coastal plains. Summer rains multiplied and brought about the spread of grasses with high nutritional value and forested land dominated mainly by acacia trees. We believe that on the beach, which used to be submerged in the sea, an extensive ecosystem of animals developed from grass beds that migrated east in the summer and west in the winter following the rains that grow fresh grass.

It is unclear exactly why the inhabitants of PP5-6 began to produce small arms after the climate change, but it may have been done to hunt animals that crossed the plain during migration. In any case, the people there developed ingenious means to produce their tiny tools: they switched to a new raw material, silcrete stones, and heated it in a fire to make it easier to shape into small points. It was only with climate change that early modern humans had regular access to firewood from the spreading acacia trees, and thus were able to make heat-treated weapon stones a permanent tradition.

We still do not know what method of casting these tiny stones were used. Marlize Lombert, a colleague of mine at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa who has studied some later examples from other sites, argues that they represent the origin of the bow and arrow, and that the pattern of damage they caused is similar to that left by arrowheads. I'm not entirely convinced she's right because she didn't investigate the damage caused by the throwing weapon. I think the throwing weapons preceded the more complex bow and arrow at Pinnacle point and everywhere else.

I think that the early Homo sapiens, like the hunter-gatherers in Africa today whose lives are recorded in ethnographic reports, discovered the effectiveness of the poison and used it to increase the killing power of the prongs. The final moments of a spear hunt are a state of chaos: pounding heart, gasping lungs, dust and blood and the smell of urine and sweat. terrible danger. An animal that has been hit and falls to its knees from exhaustion and loss of blood has only one trick left: out of a basic instinct for survival, the animal wobbles screaming and tries to stand on its feet for the last time, closing the gap between itself and the hunter and sticking its horns into his gut. The short lives and embalmed bodies of the Neanderthals show the suffering they experienced hunting large animals at close range with hand-held spears. It would therefore not be surprising that launching from a distance a kind of projectile dipped in poison, which paralyzed the animal and allowed the hunter to approach and complete the hunt without much fear, was a breakthrough invention.

the force of nature

With the combination of weapons that can be thrown into the super-society, a wonderful creature was born whose members form teams that work as one: a predator that is difficult to defeat. No prey, or human enemy, was safe. Thanks to this powerful combination of features, six people who speak six languages can row together in oars on top of waves ten meters high and allow the bell thrower to rise up to the prow at the command of the "executioner" and throw a deadly iron into the gasping body of a whale, an animal that should see no more than humans stingrays In the same way, a tribe of 500 men scattered in a network of 20 bands can be a small army to take revenge on a neighboring tribe that has invaded the territory.

This strange new mixture of killer and collaborator could explain why when the Ice Age returned, 74,000 years ago to 60,000 years ago, and again made large areas of Africa uninhabitable, modern human populations did not shrink as before. In fact, they have spread and thrived in South Africa with a wide variety of advanced tools. The difference is that this time modern man was equipped so that he could respond to any environmental crisis with the help of flexible social relations and appropriate technologies. They became alpha predators on land and eventually also in the sea. It is this ability to control the environment that opened the door of exit from Africa to the rest of the world.

Archaic human groups that didn't know how to work together and wield weapons had no chance of standing up to this new breed. Scientists have debated for a long time the question of why our Neanderthal cousins became extinct. I think the most disturbing explanation is also the most plausible. The invading modern man saw the Neanderthal man as a competitor and a threat and therefore he eliminated him. The evolutionary development of modern man caused this.

Sometimes I wonder how this fateful encounter between modern man and Neanderthal man took place. I imagine the boastful tales told by the Neanderthals as they sat around the campfire, tales of mighty battles against cave bears and giant mammoths fought under the gray skies of glacial Europe with bare feet on the slippery ice with the blood of their prey and their brethren. Then, one day, the tradition took a grim turn, the joy turned to fear. The storytellers began to speak of new people arriving on the land: quick and clever people who throw their spears to impossible distances with brutal precision. These foreigners even came at night in large groups, slaughtered men and children and took the women.

The sad story of Neanderthal man, who was the first victim of modern man's ingenuity and cooperation, helps explain the horrific acts of genocide and xenophobia that are emerging in the world today. When resources and land are depleted, we treat everyone who does not look or speak like us as "others" who compete with us, and thus we justify their destruction or deportation. Science has revealed the stimuli that trigger our innate tendencies to categorize people as "other" and to treat them atrociously. However, the fact that Homo sapiens evolved to react to scarcity in this cruel way, does not mean that we must react this way. Culture can control even the strongest biological drives. I hope that the very understanding of why we instinctively turn against each other in bad times will allow us to rise above our malicious impulses and listen to one of the most important cultural commands: "Never again".

Homo sapiens did not just follow in the footsteps of its ancestors. He paved paths into completely new territories, and changed the ecological environment wherever he went.

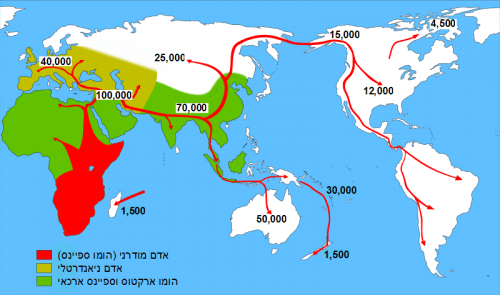

Two million years ago, after the appearance of our biological species, Homo, in Africa (purple), some early humans began to disperse outside their birthplace. They reached different regions in Eurasia and finally evolved into Homo erectus, Neanderthal man and Denisovan man (green). About 200,000 years ago, an anatomically modern human species developed: Homo sapiens. About 160,000 years ago, when the climatic conditions worsened and many of the inland areas of the continent remained uninhabited, some members of this species sought refuge on the southern coast and learned to take advantage of areas covered with shellfish and abundant with food. The author hypothesizes that this change in lifestyle led to the development of a genetic tendency to cooperate with non-relative individuals: the best way to protect the mollusk surfaces from invaders. Cooperation between individuals and social ties improved the ingenuity of our ancestors. The development of throwing weapons was a breakthrough invention.

With the advent of extreme cooperation and the development of launchable weapons, Homo sapiens was poised to emerge from Africa and conquer the world (red arrows). It spread beyond Europe and Asia to continents and island chains that had never hosted humans of any kind (light brown). Credit: “Global Late Quaternary Megafauna Extinctions Linked To Humans, Not Climate Change,” By Christopher Sandom Et Al., In Proceedings Of The Royal Society B, Vol. 281, no. 1787; July 22, 2014 (hominin habitat maps and extinction of large animals). Maps by Terra Carta.

About the writers

Curtis V. Marian

Professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University and Associate Director of the University's Institute of Human Descent. Marian is also an honorary professor at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in South Africa. He is particularly interested in the origins of modern humans and the colonization of coastal ecosystems. His research is funded by the US National Science Foundation and the Hyde family funds.

for further reading

An Early Enduring Advanced Technology Originating 71,000 Years Ago in South Africa. Kyle S. Brown et. Al. in Nature, Vol. 491, pages 590-593; November 22, 2012.

The Origins and Significance of Coastal Resource Use in Africa and Western Eurasia. Curtis W. Marean in Journal of Human Evolution. Vol. 77, pages 17-40; December 2014.

Tags: evolution articles

comments

2 תגובות

Leave a Reply

Your comment

10 תגובות

Is this really proof that the ability to believe in imaginary things is inherent in humanity?

Nice article. I'm missing the best explanation I've read in Yuval Noah Harari's short history of mankind. That the ability to cooperate in large numbers stems from the shared belief in invented things such as religion, money, people, state, limited company. It is actually a bug in the brain to believe in something unreal and false, but it actually gave the ability to share large numbers.

Of course, everything is just conjecture and the plain truth can be something rather bizarre

Finally, how beautiful

Assaf is right. Conclusions were forced on the facts and it seems that we have returned to the unfounded "sea monkey" theory. Homo sapiens is endowed with two physical elements that distinguish it from all its predecessors: a chin that flattens its face and the white of the eye (it is not clear that the Neanderthal also had a white part around the iris). These two elements create a different appearance for a person and as if he carries "two notice boards", which announce his intentions and emotions: his face and his chest (which distinguishes a male from a female). Easier

To flow in a society built on sophisticated communication (compared to its predecessors) like this and also to create trust in the individuals that make it up - and that's why Homo sapiens succeeded where others failed.

Really excellent article.

About the picture

Neanderthals are always painted as duller than the white man. Also in the drawing in the article. Is it even based on anything? Is it even possible to know what their skin color was? They lived in Europe and even in a colder period. Could it be latent racism? Maybe unconscious racism? It is true that it does not require that they were light-skinned, but there can be a high probability. They lived in cold, sunless Europe even longer than modern man.

Those who did most of the work are the viruses and bacteria, they brought with them diseases that were not known, and spread epidemics

Already at the beginning of the journey, the group multiplied with those sitting on their way, so that they were no longer exactly the common Homo sapiens

The following invading groups strengthened the control of the genes of Homo sapiens

exciting

The article is excellent, the authors' conclusions - - less so,

Because one gets the feeling that the authors marked the goal and adapted the conclusions to it,

For example:

It is known that the Neanderthals had high intelligence,

It is not known that the Spines were "smarter",

And the writers base their conclusions on the extra "wisdom",

For example:

The social links of hunter-gatherers nowadays are supposed to be equal to those of our ancestors,

Many areas where hunter-gatherers live are semi-desert to desert,

In other words, harsh living conditions which, according to the authors, were supposed to cause the joining of clans into tribes...

Or that hunter-gatherers did not "acquire" the "genetic tendency to cooperate with individuals who are not relatives"?

The paragraph in which the authors hope that:

"Culture can control even the strongest biological impulses...

…..the very understanding of why we instinctively turn against each other in bad times

Allow us to rise above the malicious impulses……'

Reflects a hope/dream for a human society that will understand that:

It's time to:

Instead of controlling the environment for the sake of the human population,

There will be control over the human population for the sake of the environment!