A suborbital space plane proposed for the US Marine Corps would land fighters anywhere in the world in two hours or less. But will he be able to overcome huge technological - and political - hurdles?

By David Ax, Popular Science, January 2007 issue, translator: Yehuda Borovik Illustrations: Peter Bollinger. The article is courtesy of the Popular Science system in Israel.

Three key facts

1 The Marine Corps sees suborbital aircraft as the means to bring its fighters almost instantly to any place in the world.

2 The technologies for the Marine Corps space plane are under development, although in a variety of programs run by different bodies of the army.

3 The aircraft will need advanced means of propulsion such as a supersonic jet engine and rocket engines, and it will have to withstand hard landings.

As any battlefield commander will tell you, bringing the warriors into battle can be just as difficult as achieving victory. And for the soldiers in our time, the combat sites are so far away, and the political considerations for flying over another country are so complicated, that entering a raid has become almost impossible. But if the visionaries from the US Marine Corps succeed, in 30 years Marines will be able to reach anywhere on the planet in less than two hours, without having to negotiate passage through foreign airspace. The breathtaking efficiency of such a flight system could completely change the way the US conducts wars.

The proposal, which is part of the Corps' push for more speed and flexibility, is called Space Transport and Insertion of Small Units (SUSTAIN). By using a sub-orbital aircraft - that is: a vehicle that flies into space to achieve high speeds but does not enter orbit around the Earth - the Marine Corps will be able to instantly transport combat units anywhere in the world. That effort is being led by Roosevelt Lafontaine, a former lieutenant colonel in the Marine Corps who is now employed by the Schaefer Corporation, a military-technology consulting firm that works with the Marine Corps. Insertion from space, explains Lafontan, allows the Marines - usually the first military arm called for emergency missions - to avoid all the usual complications that can delay or prevent important missions. There is no need to wait for a permit from an allied country, there will be no dangerous encounters in the desert, no need for slow helicopter flights over mountainous terrain. Instead, the Marines could one day have an unparalleled means of surprise that would allow them to do anything from augmenting special forces to rescuing hostages thousands of miles away.

"The SUSTAIN program is simply the ability to very quickly move Marine forces from one location to another," says Colonel (Lt. Col.) Jack Wassink, director of the Marine Corps' Space Integration Branch, which operates out of Arlington, Virginia, where the program is underway. "The space contributes itself to this task".

The program is quickly gaining traction. Congress has expressed interest, because of the obvious utility of the capability it promises. And the technologies needed to implement it, starting with a Shaga-sonic propulsion system and ending with new composite materials to make the tool light-weight but strong enough, are in advanced stages of development in military laboratories across the US. The Marine Corps hopes to fly a prototype within 15 years, most likely a two-stage system that would use a carrier plane that would launch a landing craft from high altitude. Serial models may appear around 2030, a date not so far away as it seems. Consider that the F-22 Raptor fighter jet has only just entered operational service after 22 years of development.

But the idea as a whole still sounds like science fiction, and the question is whether the backers will be able to group together the various technologies so that the project can be carried out. "The SUSTAIN program is not a pipe dream," says Lafontan. "She just needs to coagulate."

Exceeding the limits

Finding routes through diplomatically friendly airspace and then arranging a timely transfer of American forces are the main complications, especially in the current political reality. The SUSTAIN program will solve both problems at once. According to international agreement, the airspace of each country extends up to a height of 80 km above the surface of the Earth, slightly below low orbit in space. A spaceship will allow the US to pass over other countries and insert forces wherever needed.

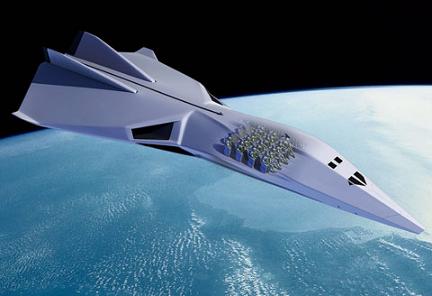

Each landing craft in the SUSTAIN program is designed to carry a unit of 13 Marines. The lander, which will be mounted on a wedge-shaped carrier aircraft, will detach from the aircraft, take off, and accelerate using supersonic jet engines to a 30 km radius, then activate rocket engines to reach a 80 km radius and fly in an arc above hostile countries. Shields made of composite materials will absorb or radiate out the scorching heat generated upon entry into the atmosphere as the craft directs itself toward the landing site.

Lafontan arrived at this vision of space marines after years of analyzing military needs in space. The 44-year-old Lafontaine, a native of Queens, New York, enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1984 as an infantry officer and advanced through the Naval Academy in Montgomery, California, where he studied space systems operations and joined a small group of Marine officers who specialized in space operations. In 2001 he moved to the Pentagon and started working for the National Intelligence Office (NRO). He was serving as a liaison officer to the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the US military in November 2001, when the Marine Corps launched its deepest air assault operation ever.

Five hundred Marines from the 15th Expeditionary Force prepared to fly 710 km over the mountains of northern Pakistan in CH-53E C-Stallion helicopters to seize a landing near Kandahar in Afghanistan. This was to be the beginning of the first major offensive against the Taliban and al-Qaeda. If all went well, the Marines expected to return with Osama bin Laden.

But political considerations sabotaged the mission. For weeks, the Marines have tottered aboard two assault ships in Indian Ocean waters as State Department officials haggle with Pakistan for permission to fly in its airspace. Pakistan allowed the transition only after winning economic and military concessions, which some claim strengthened an oppressive regime. When the American fighters finally arrived on November 25, all traces of bin Laden had already disappeared. "We had to sell our souls to the devil to get through," Lafontan says. He became determined to find a way around the diplomatic entanglement. "What if we didn't have to ask anyone for permission?" he asked himself. "What if we just pass over and land in the necessary place?"

The following April, when the Marines were locked in bloody cave fighting in pursuit of bin Laden, Lafontaine met with fellow space expert Franz Gale over lunch in the Pentagon cafeteria. Gale, also a former Marine with significant influence in the private sector, pushed New technologies for the Marine Corps' Department of Planning, Policy and Operations. Lafontaine argued that a space plane could have allowed the Marines to capture bin Laden without a major assault - and before the terrorist leader could disappear into the caves of Afghanistan. Gale was skeptical about the applicability of the plane - the idea of a military space plane has been floating around for decades, but until now they didn't believe in its implementation and therefore didn't go into actual development - but he was impressed by the elegance of the solution and its use of military technologies that he knows are in the works.

Together, Lafontaine and Gale formally presented their idea to Gale's boss at the Pentagon, Brigadier General (Lieutenant Colonel) Richard Zillmer, and then to Lieutenant General (Major Colonel) Emile Bedard, the office's deputy commander, who approved the issue in - July 22, 2002 and added the space plane to the Marine Corps' official list of requirements. But the technology - advanced reusable propulsion, sophisticated heat protection - was not ready. Just a year earlier, two joint programs by NASA and the US Air Force to develop reusable space launch vehicles had been canceled due to problems with their single-stage engines. The idea was much more advanced than the technological development curve.

But Lafontaine had patience. He continued to improve the space plane idea and push it, until the idea became fixed in the collective imagination of the space community in the Marine Corps. The SUSTAIN program soon found a home at the Marine Corps Space Integration Branch in Virginia, where Wassink directs a team of 100 satellite technicians that links Marine commanders to operations around the world. Wassink expressed interest in Project SUSTAIN, but the Marine Corps is a small force that operates under the Navy umbrella and receives only 4 percent of the military budget. "SUSTAIN is certainly not something that the Marine Corps can purchase on its own," he admits.

Zillmer agreed and presented the SUSTAIN idea to Congress. In a speech to a Senate committee in July 2003, he outlined the Marine Corps' strategy. "We must coordinate and merge our technological needs with other users in the Ministry of Defense and outside the military," Zillmer told the committee. He mentioned NASA as a possible partner. Lafontaine also predicted that the Air Force would develop the carrier aircraft and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Pentagon's experimental science arm, would oversee the landing craft's secondary. Zillmer's testimony was part of a lobbying campaign that Afontan and other SUSTAIN supporters launched to sell the idea to Congress, NASA, the Air Force and DARPA, and the industrial partners who would build the hardware. "We saw a whole range of reactions," Wassink recalled. "Some people just laughed."

. The vehicle will activate its rocket engines for the ascent into space, and then cruise towards the conflict zone [2], where it will re-enter the atmosphere and fly to land [3]."]![The future long-range lander will be launched into a suborbital path in space from a carrier aircraft [1]. The vehicle will activate its rocket engines for the ascent into space, and then cruise towards the conflict zone [2], where it will re-enter the atmosphere and fly to land [3]. The future long-range lander will be launched into a suborbital path in space from a carrier aircraft [1]. The vehicle will activate its rocket engines for the ascent into space, and then cruise towards the conflict zone [2], where it will re-enter the atmosphere and fly to land [3].](https://www.hayadan.org.il/images/content2/space/spacemarines_ss_3.jpg)

the space marines

The Marine Corps has a history of selling dangerous but revolutionary ideas. They adopted the amphibious assault before it became a decisive factor in World War II. They protected the V-22 Osprey multi-role aircraft, which features rotors that can be tilted from vertical to horizontal and back in flight, during its troubled development. And they also supported quite a few failures. Their AV-8B Harrier, which takes off and lands vertically, crashes more than any other fighter jet in service today, and it was the Marine Corps that seriously considered attaching incendiary bombs to thousands of bats during World War II.

Project SUSTAIN is one of the latest items in a long list of things that are hard to sell. However, as the world stage becomes more and more hostile and the need for a quick and flexible deployment of forces increases, Lafontan insists that "the ridiculousness factor is now gone."

The SUSTAIN program is not only dangerous, but it also requires the cooperation of researchers from several branches of the armed forces, who are now developing the relevant technologies. The SUSTAIN system will consist of two stages: a launch vehicle and a landing vehicle. In recent years, NASA, the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Navy have created plans to develop reusable launch vehicles that will utilize multi-stage systems and a combination of rocket engines and air-breathing supersonic boosters. Tools currently in development that could be adapted to the mission of the carrier for the Marine Corps - the first stage in the launcher that will carry the spacecraft - include the supersonic Falcon aircraft, which is designed to fly beyond the upper atmosphere; the Boeing X-51 and Lockheed Martin RATTLRS (acronym for: Revolutionary Approach to Long-Range Strike When Time Is Critical) test vehicles for subsonic engines; and the top-secret two-stage Hot Eagle spacecraft. This set of programs, along with aircraft engineer Brett Rutan's two-stage spacecraft, would eventually produce the multipurpose launch vehicle for the SUSTAIN program.

Falcon, a $100 million US Air Force program designed for low-orbit flights in space with the ability to take off from ground orbit, is the main promise. The first two Falcon aircraft - a long wedge-shaped aircraft - are under construction at the Lockheed Martin factories in Palmdale, California, and are scheduled to begin test flights in 2008.

hard landing

The lander is the core of the SUSTAIN program – the actual aircraft in which 13 Marines will be flown on their equipment [see illustration on the opposite page] will hover in space, re-enter the atmosphere and land right over the enemy's heads. The closest thing to a SUSTAIN lander currently flying is Rotan's SpaceShipOne, built by Scaled Composites in California's Mohave Desert. In October 2004, Spacecraft One was flown aboard the carrier to a 12.2 km altitude, accelerated from there to 111 km altitude using its rocket engine, and then landed like a normal aircraft. This unique operation, perhaps more than any other achievement by industry or researchers, has energized supporters of the SUSTAIN program. "A scaled-up model of this thing will be able to do the SUSTAIN mission," said General Pete Worden of the US Air Force at the time, watching the launch. A lander based on Spaceship-One would be larger, more powerful and armed – and adapted for long flights, as opposed to the up-and-down path that Spaceship-One flies – but the basic idea is broadly similar.

Worden, who heard one of LaFontaine's early lectures on the SUSTAIN program, is now the director of NASA's Ames Research Center in California, where he is one of SUSTAIN's biggest allies. It was Warden who lobbied DARPA to get help with SUSTAIN. But DARPA refused to participate in the program; These days, the agency is focusing on near-term projects to support the war in Iraq. But her position could change, Warden thinks. "If the US Air Force continues this and sees more applicability, DARPA may be a future player," he says.

Although a fully developed lander still seems a long way off, key technologies related to propulsion and heat shields, for both the carrier aircraft and the lander, are already quite advanced. These are aimed at making the multi-purpose launcher as in SUSTAIN strong, responsive and reusable. "One of the critical aspects of SUSTAIN is ultimately the ability to reach space in an activity with something similar to an airplane," says Wasink, who is responsible for finding technologies that could be used in SUSTAIN. "It won't help us if we have the ability to reach anywhere in the world in two hours when it will take us days to prepare the tool."

In addition to faster processes in preparing for launch, the program needs heat resistant and reusable shields instead of the space shuttle's fragile ceramic tiles, which require preparation for 60 days. And while it is understandable to everyone that there will be two stages, the answer to the question of which combination of stages is the best depends on the question. Even with a first stage like the Falcon supersonic aircraft, "there are a few different approaches" to the propulsion problem, says scientist James Pittman of NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. "The use of rocket engines to accelerate the craft to supersonic speed is one approach. Or, you can examine a solution of an engine that breathes air from the mirror for supersonic speed and landing."

Lockheed's RATTLRS program may provide important breakthroughs. This $100 million investment initiative is designed to create supersonic missiles for the US Navy, using new alloys, composites and ceramic materials to allow the engines to withstand extreme temperatures. The high-speed turbine that will be developed will eventually also appear in reusable launch vehicles, according to Lockheed's Craig Johnson. "The turbine-based combined cycle probably offers the most promise," he says, "because it allows you to operate in the low-speed range almost the same way a normal airplane does."

There are other hurdles. Dwayne Day, a space analyst, points out that Spacecraft-One is the only successful launch vehicle to date that is suitable for reuse. But, he says, its carrying capacity is limited: "If you want to carry a large number of armed fighters and their equipment, you need a much bigger ship." Another critic notes the enormous challenge of long-range spaceflight with a heavy payload—something that spaceship-one doesn't even come close to achieving. "I don't think you can carry even zero payload and do the [SUSTAIN] mission," says Preston Carter, a researcher at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. "This is beyond the achievement of normal propulsion and normal buildings."

Taylor Dinerman, a space analyst who works for Space Review, says the SUSTAIN program is feasible, given enough time for research and development. The key, he believes, will be to promote the programs that might contribute to the aircraft - and then use financial support from Congress to push the project forward. But once they get past the technological and financial hurdles, one problem will still remain. "The most difficult challenge will probably be to rescue the people," Wassink confesses - that is, to return them home safely at the end of the mission.

mission adjuncts

Historically, the Marines excel at inserting themselves into trouble spots. The hard part is getting them out of there. One option is to leave enough fuel for a short flight in normal air to a nearby base or an allied country. Lafontan and his fellow planners proposed other methods of extraction. The lander might have enough fuel to fly all the way home on its own, or, if it were a small enough craft, it could deploy a parachute and be picked up mid-air by a transport plane. Finally, since what matters is the speed of insertion and not the round trip, the extraction may require less urgency. The marines and aircraft could simply be returned by more conventional means.

At this point - after the mission is accomplished - the diplomatic challenge may really rear its head. Although officially a drone flight of more than 80 km is carried out beyond the sovereign airspace of a country, exploiting this loophole may cause political problems, something that is already foreshadowed in the new space policy of the Bush administration, announced in October, which states that the administration's intention is to exploit the space for military purposes. The SUSTAIN program does not solve the diplomatic problems it creates - in fact, the project may simply cause countries to raise the upper limit of their airspace - but it certainly redefines the concept of rapid deployment.

Whether or not the SUSTAIN program ever makes it past the concept stage, it is clear that military policymakers are seeking to increase the mobility of US forces. A Marine Corps space plane—a tool that would reduce bureaucratic delays due to political issues and reduce the potential for mission disarray—might sound impossible, but for Lafontaine and others tasked with imagining the future of warfare, it's simply the next logical step.

Washington, D.C.-based David Ax is a reporter for Defense Technology International.

5 תגובות

It will cost millions of dollars to fly to the other side of the world 13 poison-infused fighters who will die 5 minutes later from a side load that cost 10 dollars or an anti-tank missile bought for 5 dollars, or from a clutch stolen for free.

To me it sounds like an abnormal waste of money.

I wish we would be allowed to integrate in any way in this super project, Israel has the same limitations in using special forces at a distance, and not only that, this ability can be used for intelligence activity {beyond spy satellites}.

After landing what will happen to the lander?

Will you fly back?

If not, then the project is unrealistic and a waste of money.

It is not simpler and cheaper to violate the airspace of a backward country like Pakistan.