Pasteur - and definitely the final end of spontaneous formation

As we remember from the previous chapters, various scientists tried to eliminate the myth of spontaneous formation starting in the 17th century. Although they succeeded in eliminating the myth for macroscopic organisms, such as mice, flies and worms, the decisive proof against the spontaneous formation of microscopic organisms, such as bacteria and protozoa, has not yet been obtained.

Spallanzani was able to show that when he boils a bottle containing growth medium and seals it with the glass neck solder, no organisms form inside the bottle. His opponents claimed that in the process of boiling the bottle he 'corrupted' the air inside the bottle, and as a result the air was unable to support the spontaneous formation.

The main problem with air is that it is teeming with bacteria and other single-celled organisms. Even though they are smaller than we can see them, those microbes exist all around us all the time, and we breathe them in and walk among them without realizing it. In the air that has been sterilized by heating we will not be able to find all those creatures. The high heating kills them. However, in this way it is also not possible to know whether the air has been 'corrupted' and lost its 'life force', which can allow the spontaneous formation. Spallanzani was unable to design an experiment that would disprove this possibility, but the technological progress from his time to Pasteur made it possible to conduct new experiments that would prove that even air that has not been 'corrupted' cannot support the spontaneous formation of organisms.

As a simple example of one of the methods to pass sterilization air without corrupting it, we can bring the cotton plug, which was developed by a pair of German scientists - Heinrich Schroeder and Theodor von Dutsch. The cotton cork allowed air to enter bottles through tiny slits in the fabric, but the tiny organisms the air carried were too large for those thin holes in the fabric. They remained outside the cork, while the air could penetrate into the bottle. As a result, sterile air without microbes was received inside the bottle. Other ways of purifying air from bacteria included passing the air through sulfuric acid, which was supposed to kill all the microbes in the air.

Although these two methods were successful in many experiments, it cannot be denied that they were problematic and required a lot of experience in using them. Many researchers did not succeed in purifying air using them - sometimes there were too large slits in the cotton plugs, and microbes could penetrate through them into the growing medium. In the case of passing the air through sulfuric acid, it was necessary to allow the air bubbles formed in the sulfuric acid to disappear, a process that sometimes required whole weeks. If the researcher was too reckless, and did not let the microscopic bubbles disappear, then he would get non-sterile air, which still contained living and active microorganisms.

It is therefore clear why the belief in spontaneous formation did not disappear from the world at that time. For every experiment that denied its existence, there were other experiments that produced conflicting results. In the end, the success or failure of the experiment depended mainly on the technical ability of the experimenter and his attention to every detail in the planning and during the experiment. It was promising ground for Pasteur, whose talent as a brilliant experimenter is not in doubt to this day.

Louis Pasteur entered the fight about spontaneous formation following the book by Félix Armand Fauchet, director of the Rouen Museum of Natural History and professor at the Rouen School of Medicine. Pouchet published the book 'Heterogeneity' in 1859 and detailed in it the variety of experiments he conducted, in an attempt to verify the spontaneous formation. Experiment after experiment after experiment - they all led to the conclusions Pouchet wanted to prove. Indeed, in a field where it is so easy to stumble and use inappropriate sterilization methods, it is no wonder that Pouchet got the results he wanted to get. He lashed out at scientists who objected to the truth of spontaneous formation and ridiculed the claim that bacteria are in the air in large numbers.

If we ignore all the empty statements in the book, and the biased theoretical calculations presented in it, there is one particularly interesting experiment that Pouchet describes in his book and formed the basis of his belief in spontaneous formation. In this experiment, Pouchet boiled bottles containing growth medium together with some hay. The hay, as we remember from the previous chapters, contained many microbes that penetrated into the growth medium and began to multiply in it. The boiling of the bottles was supposed to kill all the microbes in the medium. After boiling, Pouchet left the bottles in the manger filled with liquid mercury, thus ensuring that they would not be exposed to dust or room air. After a few days, when he looked at the medium inside those bottles under the microscope, he saw that the medium contained masses of tiny, happy microorganisms.

According to Pouchet, this experiment was the highlight of a series of historical experiments that tried to prove the spontaneous formation. There was not a single detail in the experiment that could explain why after the medium was sterilized, organisms formed in it. Pouchet saw the results of the experiment as a decisive victory for spontaneous formation.

When Pasteur heard about Pouchet's experiment, he was already convinced that spontaneous formation was nothing more than a myth. After all, for the last six years he isolated different fermentations - tiny microorganisms - from each other, and showed that he was able to create pure solutions containing only one type of microorganism. How is it possible that the spontaneous formation is correct, if the entire science of winemaking is based on the empirical and tested proof that different fermentations do not form out of nowhere inside the solutions?

Pasteur decided to enter the fight for the spontaneous formation model because he already knew that it was not true, and believed that all his experiments so far had disproved it. His friends tried to convince him not to interfere in this area, which cannot be truly resolved. Despite their pleas, Pasteur steeled himself and tried to repeat Pouchet's experiments and understand where the error lay in them.

His first experiments were close to breaking his spirit. He repeated Pouchet's experiments step by step, when instead of hay solutions he used solutions with yeast. Of all the bottles he deposited in the mercury manger, only 10% remained sterile. Pasteur did not give up. He refused to publish these results in the general public, fearing that they would strengthen his opponent's position. Instead of surrendering to the results of the experiments, he decided to analyze each stage of the experiment and try to understand where the mistake fell. Only after several months of failed experiments, he was able to locate the problem and present it to a whole committee of scientists.

In 1861, the French government decided to settle once and for all the issue of spontaneous formation. A committee was established whose purpose was to determine whether the spontaneous formation was true or the product of imagination. The committee offered a prize to "anyone whose successful experiments will shed new light on the subject of spontaneous formation." Pouchet gladly accepted the challenge and demonstrated his experiments and their results to the committee. After him, Pasteur took the witness stand, for a performance that will be remembered for a long time for the rest of scientific history.

Pouchet's big mistake, according to Pasteur, was his reliance on the mercury manger for isolation from the room air. Pasteur explained that living things - microorganisms and their eggs - are in the air everywhere. One of the ways to see them is to shine a strong light, like that of today's projectors, in a dark room. Within the beam of light our eyes can see the floating dust grains. These dust grains are in many cases living and breathing creatures, capable of multiplying within a growing medium, if they penetrate it.

But how did these creatures penetrate Pouchet's bottles? After all, he placed the bottles in a bath of liquid mercury!

Pasteur showed that the dust can accumulate on top of the mercury and sink below its surface - thus reaching the bottles and contaminating them. In doing so he refuted Pouchet's most well-established experiment. But Pasteur was not satisfied with this. He brought to the committee two additional experiments that he designed himself.

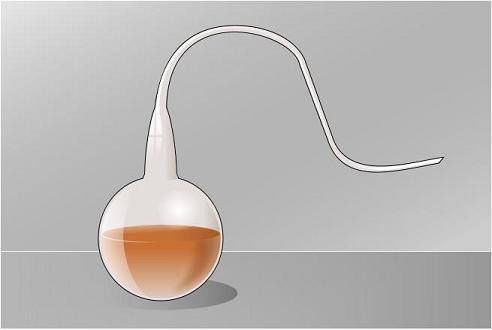

The reason, as Pasteur explained to the committee, was that the microbes are airborne, but they cannot climb the steep sides of the nozzle. When air with bacteria enters the tube leading to the bottle, the bacteria are stopped and 'stuck' in the lower areas of the tube, while the air can continue undisturbed into the bottle. Pasteur brought before the committee several such bottles that contained various organic substances, and showed that no microorganisms had formed in any of them, even though they had been in his laboratory for several months. To show the existence of microbes stuck inside the tube, Pasteur took one of the bottles and tilted it on its side until the growth medium overflowed and reached the bottom of the tube. When Pasteur tilted the flask back to its original position, the growth medium that reached the lower part of the tube scooped up with it the thin layer of dust that had formed in that area. After a few days the bottle was filled to the brim with tiny life forms, which came from the same layer of dust that had accumulated in the socket of the nozzle.

As a second experiment, Pasteur brought before the committee a series of bottles containing growth medium that had been thoroughly boiled to complete sterilization, then sealed by soldering their glass necks. Pasteur took the bottles to the top of the Montblanc glacier, where he broke their necks with tongs heated by a flame and let the mountain air penetrate them. Then reseal them by flame soldering. He performed the entire process while holding the bottles above his head, so that they would not get contaminated by his clothes. The same process was repeated on the summit of the Jura Mountains, and at the foot of those mountains.

When Pasteur tested the bottles, he found that the higher the bottles were opened, the less they became contaminated. Of the twenty he opened on top of Montblanc, only one bottle was contaminated. Of the twenty he opened on the summit of the Jura Mountains, only a quarter became contaminated. The reason is clear - in such high places there is less dust in the air, and therefore there is less chance that one of the microbes will find its way to the opening of the bottle. For comparison, when Pasteur repeated the experiment with thirty bottles, but this time inside a crowded inn in the area of the same mountains, ten of them became contaminated. The air in the inn was densely populated with microbes, and the result was that even a short exposure of a few seconds to the air in the room caused the contamination of a third of the bottles.

The committee accepted all of Pasteur's arguments and experiments and the room was filled with applause when he finished his demonstration. The only one who did not applaud was Felix Pouchet, who decided to withdraw from the competition a few days later, on the pretext that the members of the committee were biased in favor of Pasteur anyway and that there was no point in continuing the pretense. The committee determined that Pasteur won the prize, and declared that the theory of spontaneous formation was abolished once and for all.

But was Pouchet right in accepting it?

To understand the position of the committee members, we must look at the social science of those times. Two years before the commission, Darwin published his book 'The Origin of Species', which supported the theory of evolution through natural selection. This book caused a great uproar in all European countries and especially in Catholic France, and many scientists and clergy opposed the theory of evolution presented in it. This theory states that all living things evolved from some ancestor, which is probably a primitive cell that was created at the beginning of life. But how can such a cell be formed?

According to the theories available today, the first cell was created as a result of a series of processes that lasted hundreds of millions of years. But according to the belief in the 19th century, the only way such a primary cell could be formed is, of course, by spontaneous formation. Therefore, the members of the French committee, who were devout Catholics, had a proven interest in determining that spontaneous formation is unsustainable, thus also canceling the young theory of evolution. To this day, you can find websites of 'creationists' - people who believe in the creation of man by God - who quote the words that Pasteur gave before one of the French committees: "The doctrine of spontaneous creation will never recover from this mortal blow."

Indeed, Pasteur was right. The myth of spontaneous formation no longer exists in science. But the creationists who believe that evolution is invalid because of the refutation of that myth, do not understand the theory correctly. The spontaneous formation of whole cells is not possible nowadays and during human life, but it was possible at the beginning of the earth, when the conditions were very different and there were no living beings to eat the initial cells that were formed. We still don't have all the evidence for the creation of the primary cells in this way, and most likely never will, since hundreds of millions of years have passed since that time. At the same time, we can discover the remains of the genome of those primitive primitive cells in all the creatures that exist in the world today, and new evidence accumulates every year showing how inert organic molecules can, under the right conditions, assemble to form complex structures, from which the primitive cell could have evolved.

Pouchet, then, knew what he was talking about when he accused the committee of bias - even if he was wrong in his experiments. And despite these facts, it is possible that if he had remained before the committee, he would have won the award. In the chapter dealing with the fight between Spallanzani and Needham, we talked about the problematic properties of the spores found in the hay. These spores do not die even at very high boiling temperatures, but only with the alternating boiling method, in cycles of several hours of heat and cold. Pouchet, as I recall, created his growth medium from hay solutions, which, even if they were boiled well, still contained the live spores. No wonder all his experiments were contaminated!

And what about Pasteur? Why did that wonderful experimenter decide to work with a growth medium containing yeast, and not use the growth medium containing a hay solution? In Pasteur's laboratory protocols we find no mention of him ever trying to use a hay solution in his experiments. If Pasteur wanted to disprove Pouchet's experiments in any way, he should have used the same medium as Pouchet used!

We can imagine a possible scenario in which Pasteur fails to eliminate the hay spores despite feverish sterilization. When he realizes that, despite all his efforts, he is unable to disprove this part of Pouchet's experiment, he ignores it altogether and switches to working with yeast solutions, which are easier to sterilize. He burns the laboratory notebooks describing the period in which he experimented with the hay solutions, and hopes that no one will ever wonder about this point.

We can imagine such a scenario. But I don't believe it corresponds to reality. From all we know of Pasteur's character, it cannot be denied that he was cunning, jealous of his own opinions and completely intolerant of the opinions of others. But although he was able to intentionally mislead the audience of his lectures, he never gave up his self-righteousness. All of his experiments are documented, one by one, in his laboratory notebooks that were revealed to the public in the 20th century. If Pasteur had discovered the problem of sterilizing the hay spores, he would have mentioned it in his laboratory notebooks. He certainly wouldn't have burned them - he guarded them with the utmost care. Moreover, a person with Pasteur's experience in inventing new experiments and new techniques for treating microorganisms would surely also have succeeded in solving the problem of sterilizing the hay spores. From the moment the problem of hay spore sterilization was discovered in the seventies of the 19th century, the solution was found in repeated heating of the growth bottles, which even the most resistant hay spores cannot withstand. It is hard to believe that Pasteur would not have come up with such a simple technique on his own.

the end of the story

After the commission of 1861, Pouchet tried to repeat Pasteur's experiments in the mountains and got, as expected, very different results. He convened another committee in 1864, and it too encountered a wall of opposition, side by side with a public appearance by Pasteur whose fascinating content can even be found online today (http://shell.cas.usf.edu/~alevine/pasteur.pdf ). Faced with these two, Pouchet decided to resign from the committee for the second time, and public support for Pasteur grew even stronger.

The spontaneous formation returned to the headlines in 1881, 20 years after the original committee where Pasteur presented his findings. An English biologist named Henry Charlton Bastian discovered new spores that were not easily destroyed by the usual methods of sterilization. From those few spores he tried to revive the idea of spontaneous formation. When Pasteur heard about Bastian's experiments and claims, we cried out: "God, haven't we freed ourselves from these beliefs yet? Lord of the universe, this is not possible!" [F] He went over Bastian's experiments and showed the general public the problems in their design. Two English scientists also joined Pasteur's fight against spontaneous formation at that time: the first is John Tyndall who developed a dark box with a hole through which a strong light shines into it. In this way he could see the microbes floating in the air of the box, and when they sank to the bottom of the box, he could take the germ-free air and prove that it was completely sterile. The second scientist is Joseph Lister, who brought about a revolution in the world of surgery and post-operative infections, which we will discuss in the next chapter.

Despite all the evidence against spontaneous formation, Bastian died in 1915, still imbued with his belief in the righteousness of the way. It is quite possible that he was the only scientist in the Western world in those years who still believed in spontaneous formation.

Summary

Today there is not a single biologist who believes in the creation of microorganisms out of nothing. Millions of bottles of growth medium are created every day in laboratories around the world, and as long as they are kept under sterile conditions no living organisms are created in them, even if many years pass from the moment of creation to the moment of opening. Disproving the myth of spontaneous formation opened a door to the science of medicine and microbiology through which scientists were able to understand how to fight diseases and infections. If not for Pasteur's struggle with Pouchet, it is possible that the successful refutation of spontaneous formation would have taken many more years - where each such year would have delayed the research even more and meant the death of thousands more people from diseases and infections that could have been prevented and stopped.

The next chapter will be dedicated, as we wrote, to Lister, the father of the modern operating room and the man who saved the lives of thousands of people thanks to his unwavering support for the sterilization of operating rooms.

Part I of the article

Part B of the article

Part III of the article

6 תגובות

Thank you,

Very interesting and waiting for most.

lion,

Thanks for the attention to detail and the constructive criticism. I will fix it soon.

Day-Walker,

thanks for the correction. It's hard for me to argue with Shapiro's expert opinion (whatever without hearing his lecture), but I find it hard to believe that he supports the formation of entire bacteria out of nothing, even if they are the bacteria of the 'RNA world'. Such a creation in a short time does not seem reasonable (and of course, one can use the common parable of the creationists, which is precisely appropriate in this case: what is the chance that a calculator will be created from nothing?)

Do you know about nucleotide solutions that spontaneously crystallized into RNA strands?

Good night,

Roy.

A small correction regarding "today there is not a single biologist who believes in the creation of micro-organisms out of nothing".

It should be "today there is not a single biologist who believes in the *widespread* out-of-nowhere formation of microorganisms".

In December 2007 I participated in the 21st meeting of the Israeli Society for the Formation of Life and Astrobiology (ILASOL - search on Google). The guest of honor at the gathering, which took place at the Weizmann Institute, was Robert Shapiro, one of the oldest researchers in the field.

Shapiro claims that it is certainly possible that spontaneous formation is more common than known (though of course not on the pre-Pastian scale). The reason we miss these life forms, according to him, lies in their inability to survive against the dominant life forms on the one hand and the use of standard methods *immediately* to discover life forms on the other hand (the bacteria of the RNA world will grow on LB plates?)

But apart from this minority opinion, great review.

Thanks for the informative articles. I feel petty making a few small comments, but we'll treat it as proofreading.

Twice in the article the years 19XX are mentioned while the reference is of course to 18XX.

Shortages and non-shortages. Keaton is something else.

The first cells were created billions not hundreds of millions of years ago.

"A public performance by Pasteur, the fascinating content of which can be found on the Internet to this day" - it's not that they put it on the Internet in 1864 and it remains to this day...

Dan,

I promised and I will, but the chapter on rabies and anthrax will come only after the stories of Lister and Koch - two other important scientists who worked in Pasteur's time - and will complete the overall story.

I'm glad you enjoyed it,

Roy.

Fascinating articles!

You also promised us the episodes of Pasteur with the rabies and anthrax diseases...