The marriage of convenience between the military and science, even if it raises doubts, is important for the progress of science. Relations forged with NASA as part of Ilan Ramon's flight into space could bear fruit for Israel

When the space vehicle Columbia lands tomorrow in Cape Canaveral, Florida, more than two weeks of orbits in space will come to an end. This flight, the 113th in the number of the American space agency NASA, indicates more than anything else the routine into which the human race entered in its ability to disconnect from its planet. Over half of humanity was born into the space age, the one that began with Yuri Gagarin's first flight in 1961 and continued with Neil Armstrong's exciting steps on the moon in 1969. But this routine must not mislead you: even today, after about 40 years, every ferry shipment is a remarkable achievement.

The main problem in space flight is overcoming the Earth's gravity. According to the floating of the astronauts and their belongings around the spacecraft, one could think that they had reached such a great distance that the force of gravity did not apply to them. In fact, they are exposed to the low gravity of only 8% of that which prevails on the surface of the earth. The levitation effect is due to the fact that the shuttle, in its circular orbit at an altitude of 250 kilometers, is essentially in a state of constant free fall. Its passengers experience what a passenger in an elevator in a skyscraper would have felt if the cable had been disconnected and the cabin had fallen without interruption. A similar insight led Einstein to formulate the theory of general relativity, which allows cosmologists to understand the origin of the universe and its structure. In order to achieve such a prolonged "fall", the spacecraft must fly around the Earth at satellite speed, about eight kilometers per second, which means a journey from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem in nine seconds. According to Newton's first law, and due to the lack of friction in space, the shuttle and its passengers will continue to move at this tremendous speed until the braking engines are activated. But in order to get from rest to satellite speed, a force that creates acceleration must be applied, as required by Newton's second law. Indeed, with the help of acceleration such as that acting on a typical Israeli driver when the light changes at a traffic light, it will take almost an entire hour of hard pressing on the pedal to achieve satellite speed. Accelerating, the car will go all the way from Tel Aviv to Shanghai.

In reality, the process takes about five times as little time, and the spacecraft is 1,000 times heavier than a car. Therefore, 5,000 times greater power is needed, which is provided by the huge rocket engines. In the wake of these, excitement rises in all who observe the launch, as the spaceship rises slowly from the launch pad, surrounded by clouds of smoke and fire. A tiny mistake in their operation, for example a seal that froze and cracked, can cause a terrible disaster, such as the one that occurred a minute after the launch of the space shuttle Challenger in 1986. Launching a man into space therefore requires a technological and computing ability that is not simple, which only the two great powers, the United States and Russia, have. The forecast is that China and Japan will soon join them.

The deep reason for space travel is scientific curiosity. The space programs in the United States and Europe are fueled by the desire to understand the universe, the planets and the origin of life. But it is an unfortunate fact that in all the countries of the world basic science is placed low in the order of priorities. The rescue comes from the fact that certain basic researches are supported by governments for considerations important to security. Indeed, the space age began due to the Cold War, and its missile technologies were derived from the arms race, including beginnings precisely in Nazi Germany. This marriage of convenience between the military and science, even if it causes certain doubts, is important for the progress of science.

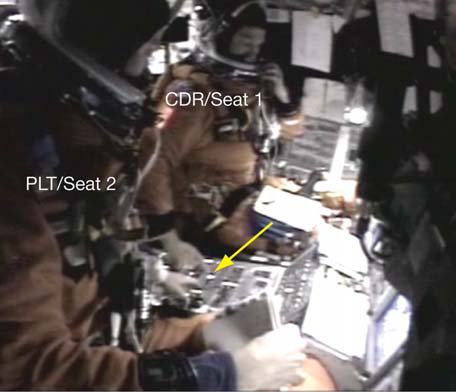

Although Israel is high on the list in the ability to launch satellites, so far it has had almost no contact with manned launches. It goes without saying that we cannot send an astronaut into space ourselves. Passive sharing of the type of conducting an Israeli experiment on board the spacecraft allows only a loose connection to the complete array of science and technology involved in launching the shuttle. That is why Shimon Peres' initiative in 1996, when he convinced President Bill Clinton to include an Israeli in the program, should be congratulated. As in other cases of "big science", for example using high-energy particle accelerators in physics or sequencing the genome in biology, the initial goal of scientists from a small country should be "partnership in the club". This is a necessary condition for deeper involvement later on. Undoubtedly, the deployment of Lieutenant Colonel Ilan Ramon would not have come to fruition without the financial support of the security establishment. The money invested may have subtracted a tiny percentage from the budget for the purchase of anti-tank air missiles, but it certainly did not come at the expense of any other research budget in the country. The Israeli astronaut project should be seen as a welcome diversion of additional budget for purposes that are essentially scientific. Due to the involvement of the security system, it is natural that a highly experienced pilot was chosen for the mission. It is also likely that this made it easier to agree to share an Israeli on the flight and shortened the training. There was no detail in the scientific duties of the first Israeli astronaut that a university professor would have done better. From the point of view of a small and poor country like Israel, the very direct contact with the diverse teams and with the lively activity on the technological front holds promise. In a negative international atmosphere in which there are daily news and proposals to expel Israel from scientific forums, such sharing is even more important. The sight of the Israeli flag on the shoulder of the astronauts' overalls may contribute to Israel's deteriorating public relations more than dozens of speeches by Foreign Ministry envoys.

It is also worth asking when the topic of space flights was recently headlined in the Israeli press. This probably hasn't happened since the Challenger crash. The featured news that appeared this week will surely contribute to bringing the public closer to astronomy, earth research, meteorology and astrobiology. Even modest experiments like those in which Ramon also participated, for example watching dust storms and clouds, can be useful for promoting scientific literacy in Israel and around the world. It is enough if we refer to the positive coverage that the observations from the deck of the shuttle received in "elves" - unexplained circles of red light sent into space from storm clouds. This is compared to the humiliating treatment suffered by scientists and journalists in Laos who dared to scientifically investigate glowing red balls on the Mekong River, which the locals attribute to the fire-breathing dragon that appears once a year.

Manned space flights are now at an interesting crossroads. On the one hand, it can be said that we have stagnated after the exciting years of the Apollo program to land on the moon. On the other hand, an international space station is now being established and it will be able to serve as a realistic springboard for a human landing on Mars by 2010, as implied by the announcement of the US president a week ago. Even if the Israeli Space Agency is a little understaffed these days, there may be a radical change in the not too distant future. Relations forged with NASA in the framework

Ramon's flight will be able to bear fruit.

Let's imagine that a trip to another sun, such as the star Alpha Centauri, which is 4 light years away from us, is like a flight from Tel Aviv to Los Angeles. On the same reduced scale, the distance to the moon is a small step of about 15 centimeters, and the flight height of the space shuttle is truly microscopic - as thick as a hair. Looking into the distant future, our space age is only a tiny first step on a very long road. And just as scientists in the State of Israel make a supreme effort to contribute to future developments such as nanotechnology, protein engineering, supercomputing and robotics, it is fitting that we also take part in sowing the first seeds in the journey into the universe. The two weeks that the Israeli astronaut spent in space are a worthy start to this kind of effort.

Editor's note. The day after this publication, the Columbia disaster occurred, in which Ilan Ramon and his crew members perished.