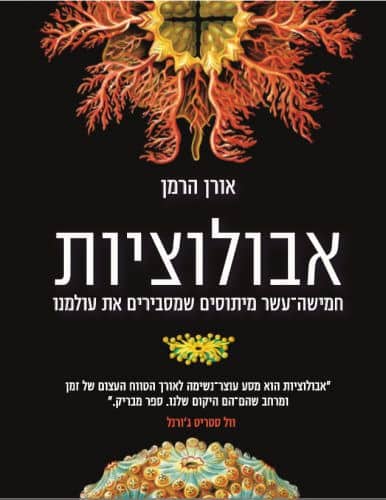

A chapter from Oren Herman's book - Evolutions Fifteen Myths That Explain Our World by Oren Herman

From English: Nir Rachkovsky, Attic Books Publishing and Yediot Books

In the new book "Evolutions Fifteen Myths That Explain Our World" Oren Herman returns to the ancient themes of myths with the help of modern science. Every culture makes use of its language to crack the existential questions. Prof. Herman is interested in understanding the differences between science and myth but also insisting that they are more similar than we imagine.

This month, Prof. Herman won the Bar-Ilan University Rector's Prize for Scientific Innovation for his book XNUMX

The ancient Chinese believed that the world emerged from an egg, the Maori that it was created from the rupture of an embrace between the goddess of the earth and the sky. We replace these stories with solid facts: the big bang, the expansion of the universe, physical forces and laws. Many think so.

But a more controlled look at science teaches us that it never directly describes reality, but with the help of a model, and it always mediates through contemporary language. Take for example the brain, which in the sixteenth century was considered a miniature hydraulic system inside the skull, in the seventeenth century a complex mechanical clock, then a telegraph switchboard, a network of neurons, and some speak of it today as a quantum computer.

evolutions by Oren Herman is a unique book, which combines fragments of poetic myths with an updated scientific description of the development of the universe and life in it - from the Big Bang to us, humans. This is a book that is both delightful and mind-expanding to read, a rare combination of literature and science - a book that will make you want to open up to new and unfamiliar spaces of knowledge, as well as read ancient mythologies and go down to the roots of human knowledge. Here we will see the earth and the moon present a new cosmological view of motherhood, we will get to know the mitochondrion that gave birth to sex and death, and we will discover how the birth of language during evolution invites the human race to face the truth.

Prof. Oren Herman He studied biology and history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Oxford and Harvard. Later he became a historian of science and a writer. his book The price of altruism (published by "Attic Books") won the Los Angeles Times award, was selected for the New York Times books of the year list and served as the basis for two plays. Herman is the head of the program for science, technology and society at Bar-Ilan University and a senior research fellow at the Van Leer Institute in Jerusalem, where he hosts the lecture series Talking about Science in the XNUMXst Century and leads the "Science and Creativity" research group. Among his books: The Man Who Invented the Chromosome, a trilogy about Rebels, Outsiders, Dreamers in biology, and the book Evolutions: 15 myths that explain our world (published by "Attic Books"). His books have been translated into Chinese, Hebrew, Japanese, Turkish, Italian, Korean, Polish and Malayalam.

"Evolutions is a breathtaking journey across the vast expanse of time and space that is our universe. A brilliant book.” Wall Street Journal

Jealousy - the invention of the eye

1

My ancestors could not see, but I can - the world and its wonders. I don't know if I got paid for it. In fact, if I could go back in time and undo the invention, I would do so without hesitation. Those eyes brought me too much pain.

2

The next supercontinent after Rodinia was Pannotia. But not long after, she too began to fall apart. In the south, Gondwana weakened at the pole and stopped the ocean currents. Laurentia, Baltica and Siberia migrated north. The earth was frozen. Gradually, as the large glaciers melted, the water surface rose and flooded large land shelves with shallow, warm water. With another tiny increase in oxygen levels, a new era opened, different from all its predecessors.

Darwin's teacher, Segwick, called it the Cambrian era, because the first fossils were dug up in Wales, whose Latin name is Cambria. You know: we both lived this period in real time. From the Canadian Rockies to Chengyang in China, from Sirius Pass in Greenland to the Namibian deserts, one day the full extent of that evolutionary explosion will be known. Ediacara's garden was sparse in comparison. In the Cambrian era, which began 542 million years ago, life became a war.

3

At first my mother taught me, without words: be careful. you are soft There are a lot of things out there that will want to hurt you.

How could I know what to look for, and what to watch out for? I had no eyes, only pores. It was the water that brought me all the good news: dangers lurking in the shallows, distant dreams somewhere in the depths. A stream in front, a cold stream behind - everything seeped in like hesitant whispers, equally distant from my heart. It was my world, hanging on the edge of a water ripple, the sum total of my desires, the source of all my fears and hopes.

Sometimes the rocks surprised me: angular, pointed, like railings, cold. They were my first teachers, teaching me texture and form. But as my nose bone took shape, and my sense of smell strengthened, I saw the world differently: through smells of nearby basins, grainy news about underwater skirmishes, bursts of currents that warn of plate movement. This is how I first learned that the continents were moving, that the world was coming apart at the seams.

For millions of years our family lived near a calcite deposit. We absorbed our surroundings, and with each additional drop of the transparent mineral that sank into our bodies, the shadow cast by the objects grew sharper. At first my ancestors could only see hints of movement, a blurred dance of light. But one day the minerals combined inside me in just the right amount, like raindrops that collect on a leaf and quench the thirst.

All of a sudden, the world seems to be compressed into hexagonal-shaped sticks. The calcite that lodged in the space between the tissues was used as a lens, an aperture was formed, and the resolution was divided by the size of the hole. As the number of the sticks increased, the world became sharper and more focused. Like the animals of the Ediacaran era, my ancestors were idlers, passively accepting what life offered them. Now all this changed in a moment: without being summoned, the sight came into the world.

These were not the swollen, colorless eyes of a Humboldt squid, or the stunned gelatinous eyes of a carp, the monocular eyes of a lobster, the squinting eyes of a fly, or the enchanted eyes of a lemur. Because there were no trees, lemurs and flies in the world yet, nor lobsters, carp or squid. There was no vitreous gel, nor eyelids.

But there was an optic nerve, a retina and a cornea, and more than a thousand complex crystalline lenses, each made of calcite clasts grouped together in the structure of a camera. Each of them tilted in a certain direction, like a honeycomb, and took in a narrow piece of landscape. This is how the world looked for the first time, in all its pixelated glory.

4

I became a frightened creature, but almost instantly, also a believer. All around me I could now see the ravenous Opabinia and Lucigenia, and also the ferocious Onomalocaris with its jointed limbs and panting gills and double tusks that cast menacing shadows on the sea floor. My stomach clenched at the sight of these horrifying plays. But they also carried a hint of redemption. Because if I have the ability to see the danger, I can also hope to escape it. From then on, fear and hope went hand in hand, like a pair of parasitic twins.

I looked here and there, measuring the distance to the things around me, my eyes took on the role of the house mathematician. If I leap to that rock, there, at the foot of the sea-lily, I shall have safe shelter. I admit that the calcite trampled armor near my eyes, in order to defend myself better. I also had a matching head guard. With the help of chance and natural selection I overcame my mother's fears. But against the teeth of the larger beasts my armor was not enough. That's why I tried on myself. For a moment I hid under a rock, forgotten by the world, grateful.

Then I saw you, in all my three thousand hexagonal eyes, floating in the rays of the sun above me. You look like Tamar to me, maybe like a young Cassandra. If beauty sometimes appears fragmented, it happens because it is a product of that first refraction: composite, dancing between the spears of sunlight. I don't know much about my feelings, but I could sense something mystical. The sight brought panic to the worlds, but it was immediately followed by desire.

5

I could see that you were like me: articulate, three-lobed. Like me, you had hairy tentacles, and branched limbs, and a ribbed chest, and a head shield, and a free cheek, and armor. If you wanted to, you could swagger, and gather thorns, and shed your mantle - just like me. But most importantly, your calcite crystals were arranged in layers just like mine, to ensure perfect transparency, like the work of a master builder. One day humans will use limestone to build the pyramids of Giza and the foundations of the Parthenon. But nothing will be as perfect as our ancient trilobite eyes.

We both knew: in a world without sight, we would continue to smell and feel our way. Instead of wistful glances, tangled caresses and scent festivity were common. Ears could also thrive, spurring the creation of delicate symphonies. The language of love was written in rhymes of vibrations, sonnets of texture, maybe even in poems of smell. There were no winks, or sideways glances. And of course we wouldn't know anything about the "blindness" of love.

But the hand of chance provided us with crystal clear eyes. And by reading the mosaic of the world through the living rock, they became the queens of our senses, relegating the other senses to the rank of servants. We had need of our eyes in these muddy bottoms of the sea, where malicious animals disguise themselves as algae, and worms burrow under the ground; where neighbors become traitors, and nothing is as it seems. When the eyes came into the world, the world accelerated its course. Instead of casualness, conspiracies appeared. Instead of Tom - power. The eyes were a death blow to faith: from now on it was to see or be seen, eat or be eaten. Thus the war broke out.

But I forgot all this, there, from my hiding place near the sea lily, while I was crouching down and looking at you with the moons of my ancient eyes. I had forgotten the lurking Opabinia and the hungry Lucigenia, and also the ferocious Onomalocari with their jointed limbs and panting gills and double tusks casting their shadows on the sea floor. I forgot the thieves and pickpockets. I forgot the war and the ambush for prey. In the faint lights that pierced my crystals I saw you. And I only wanted you.

6

Many years later the scientists will claim that with the eyes comes movement, with movement competition, and with competition specialization, with specialization differentiation, and with differentiation - the big bang of life. It was the eyes, they said, that brought about the rapid change of the Ediacaran era to the Cambrian era, and filled the earth with a variety of species. The eyes were a blessing, a great secret, and magic. And that's why they were invented, time after time.

And yet, I am the one who perfected sight to perfection, even if other creatures with simple eyes saw partially before me. I was the one who first examined, behind the rock, the full potential of the invention and its consequences. I don't know if the scientists are right, because I'm just an extinct trilobite. But I can tell you that there was no "Cambrian explosion". And more than that: eyes are a curse.

Because from my hiding place in the murky waters, I could see that day that your stony gaze was fixed elsewhere; That the sea lily, iridescent Achmatocrinus, fluttered in the shallow water and caught your eyes. You couldn't blink, which doubled my pain. You were mesmerized as you watched her nine arms dance in front of you with infinite gentleness, and nothing I did could make you turn your gaze to me. I silently watched your every move. And I could sense the dozens of male trilobites around you, peering lustily out of the cracks of their hiding place with their dirty eyes, rubbing their tentacles with pleasure, preparing to pounce.

This is perhaps how Hades felt when he looked at Persephone standing in a field in Sicily, mesmerized by the violets. Maybe he couldn't help himself either, and owed her to himself, like me. But he was a god, and I indeed dwelt in the bottom of the ocean, but I was only an arthropod. Hades could get anyone who wanted her; Whereas I longed only for you.

In my defense, you broke a heart I didn't know I had, but what was I supposed to do? Like everyone else, I obeyed the instructions of the game. You became my victim not through your fault, but out of a Darwinian imperative. There was silence as I raped you in the calm water above the rock.

300 million years we lived, both of us, longer than the dinosaurs. By all accounts, it was a successful experiment. I know that looking through my eyes means seeing the world as bits of information: maybe I should have been called a trilobyte. But please, at the very least, let me apologize: I learned about passion and survival the hard way, through the eyes. What a shame that it turned out that they are the exact same thing.

From the kingdom of extinct species, I plead with pain and hindsight to the gods of luck: take my eyes and never give them back to me. To hell with all damn life forms, to hell with evolution. I would rather die a thousand deaths in the jaws of Onomalocaris than see through them even one more time.

Enlightenment

According to the geological record, the Ediacaran era was followed by the Cambrian era, which is usually dated between 542 and 488 million years before our time, and is often described as a revolution in the history of life. To begin with, this era was dramatic: Charles Darwin even noted in the Origin of Species that this was one of the strongest counter-arguments to his theory of gradual evolution. Whereas earlier creatures were relatively small, few, lacking armor or weapons, and on the whole content with themselves and not interested in others, here now suddenly appeared in the world a multitude of complex animals, predatory and responsive to each other, as if a curtain had suddenly been lifted behind which they had been hiding all along . In the blink of an eye, in evolutionary terms, the rate of species diversification has doubled by several orders of magnitude. As the American paleontologist Steven J. Gould colorfully described it in his book Wonderful Life, suddenly a host of hard-shelled arthropods such as Hallucigenia, Opabinia and Anomalocaris appeared, equipped with a developed nervous system, articulated limbs , gills, tentacles, claws, and even impressive tusks like a mastodon. Such monstrous creatures swam to them among delicate water lilies like Echmatocrinus, a creature that resembled a flower attached to the bottom of the sea by a stem and on top of which colorful waving arms. Due to the abundance of life it suddenly brought with it, that period is known as the "Cambrian explosion".

In recent years, criticism has been voiced towards the accepted opinion: was there really an "explosion" in the Cambrian era? Many scientists are no longer so sure. New finds from China, Greenland and Namibia show that a wide variety of complex creatures existed already at the beginning of the Cambrian era. It seems therefore that Darwin was right: life appeared more gradually. As the British paleontologist Richard Fortey wrote in his book Trilobite: Eyewitness to Evolution: "When a play (especially a thriller of the 'Who's the Killer' type) starts to falter a bit, one of the proven 'tricks' to bring it back to life is to introduce an explosion. boom! The audience jumps and jumps, and of course, under the cover of a gunshot, it is possible, from a dramatic point of view, to commit murder and escape guilt."

Whether the word "explosion" is misused or not, it is clear that in the period between 650 and 500 million years before our time, almost all the basic body schemes known to us (and many more that have become extinct) appeared and flourished on Earth. Fierce controversy arose over the question of why this happened, and in recent years attention has focused on oxygen. The increase in oxygen levels in the oceans, it is argued, allowed organisms and their nervous systems to become more complex. See Douglas Fox's short article "What ignited the Cambrian explosion?". For further insight into the possible role of the developing nervous system, see the article by Detlev Arendt, Maria Antonieta Tosches and Heather Marlow (Arendt, Tosches & Marlow).

One of the complex mechanisms attributed to the increase in oxygen levels is the eye. It is possible that primitive vision began to develop as early as 750 million years ago, but the first fossilized eyes belong to a class of about 20,000 species of marine arthropods, some as small as mosquitoes and others as large as giant turtles, and all of them have three vertical lobes: the trilobites. The eyes of the trilobites - the only ones ever made of calcite - were amazing devices. Researchers Euan Clarkson and Ricardo Levi-Setti (Clarkson & Levi-Setti) showed that these eyes conjured up plans drawn up in the 17th century by the Dutch scientist Christian Huygens and the French mathematician-philosopher René Descartes as an optical "solution" to the spherical labration. As Forti writes: "It may indeed be a wonderful example of art that imitates nature, or perhaps of nature that precedes science - by more than 400 million years." For a more general overview of the evolution of vision in nature, see George Glaeser and Hans Paulus's colorful and accessible book, The Development of the Eye.

The eyes of the trilobites, which were made of rock embedded in armor, did not blink: one of the species was even called Opipeuter inconnivus, a combination of Latin and Greek which means "the one who looks and does not sleep". They were composed of calcite sticks - sometimes thousands in number - and allowed an incredibly sensitive observation of the landscape. Researcher Kenneth Towe, from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, even photographed from the laboratory window, through their lenses, the FBI building across the street (don't tell the authorities). Certain species of trilobites have lost their eyes during evolution, but there are no known examples of eyes being lost and replaced: it turns out that vision is a one-way street.

The "light switch" theory of Cambrian diversification posits that eyes kicked evolution into high gear by improving locomotion, thereby increasing predation, leading to an "arms race." To defend themselves, marine arthropods, including the trilobites, developed hard exoskeletons made of calcium carbonate, thanks to which so many of their fossils have been preserved. As inventions multiplied, so did the number of species, and life became more and more diverse. Thus, with the help of a little oxygen, the eyes shaped the animal world. For an overview of this idea see Andrew Parker's book In the Blink of an Eye: How Vision Triggered the Big Bang of Evolution.

It is also possible that the eyes brought with them behaviors that led to a different kind of competition. We don't know much about the sexuality of the trilobites, but it seems that sexual selection was in full swing, meaning that not all males could get what they wanted, hence the surprising twist in the story. You will find evidence of this in the article by Robert Nell and Richard Fortey (Knell & Fortey).

The rape of Tamar, daughter of King David, by her half-brother Amnon, is told in 24 Samuel, chapter 11; The rape of Cassandra, daughter of King Priemos and Queen Hekuba of Troy, by Aias "the swift" (as opposed to Maias "the great", son of Telamon) - two characters mentioned in chapter XNUMX of the Iliad and chapter XNUMX of the Odyssey - is told in fragments by the ancient Greek poet Alkaios, XNUMXth century BC; And the rape of Persephone by Hades is mentioned in the "Homeric Hymn to Demeter", a poetic work from the seventh or sixth century BC.

Among male trilobites resorted to using coercion to survive or not, the eyes - real as metaphorical - are a blessing with a curse on the side.