A revolutionary new look at human evolution adds a decent dose of luck to the usual story, highlighting our ancestors' ability to use tools

Humans are very strange primates. Our upright walking endangers the balance of our heavy body carried on two short legs. Our heads are oddly sized: tiny faces and small jaws tucked under our large skull, which resembles an inflated balloon. And perhaps the most amazing thing is that we process information about the world that surrounds us in a way that has no equal. As far as we know, we are the only creatures that mentally decompose our environment and our inner experiences into a collection of abstract symbols, which we roll over in our minds and create new versions of reality from. We are also able to imagine what could be, and not just describe the existing.

But our ancestors were not such unusual creatures. The fossil record clearly shows that a little more than seven million years ago, the primitive species from which we evolved was an ape-like creature, a tree-dweller at its core, that carried its weight on four limbs and had a large, prominent face and strong jaws behind which lay a rather modest brain box. It is very likely that his consciousness was largely similar to that of modern day chimpanzees. Although today's apes are intelligent, resourceful animals and even know how to recognize and combine symbols, they seem unable to arrange them in such a way as to express a new state of affairs. The transition from that ancestor to our species, Homo sapiens, therefore required rapid evolutionary changes.

Seven million years is a period of time that may seem long, but in evolutionary terms it is a rather short period for such a transformation. To illustrate how fast the change was, consider that usually closely related primate species, and certainly those belonging to the same biological type (genus), do not differ greatly from each other in their physical and cognitive characteristics. Moreover, scientists estimate that the average lifespan of a species of the mammal family is about three to four million years, about half the time of the existence of the hominin group (which includes us and our extinct human-like relatives), during which this group changed beyond recognition. If evolutionary histories are built from progenitor species that give birth to offspring species, and we know that they are built that way, then the rate of differentiation, that is, the appearance of new species, must have greatly increased in the human lineage, otherwise it is impossible to explain the extreme changes that have taken place.

Why was evolution particularly fast in our family? What was the mechanism that caused this acceleration? These questions are obvious, and yet, surprisingly, they have not particularly intrigued the scientists who have studied human evolution through fossils. There is almost no doubt that the answer includes the ability of our ancestors to face the challenges that stood before them with the help of stone tools, clothes, making shelters, lighting a fire, etc., findings called "material culture", since they teach about the lifestyles of those who use them. Scientists have long believed that natural selection favored those early humans who were good at inventing and sharing their cultural knowledge with each other. The more talented individuals survived and reproduced more than others, and thus the entire hominin group steadily progressed.

But this refinement, generation after generation, could not have been fast enough to so radically change the human lineage in seven million years. As we learn about the climate changes that took place in the last two million years, a new picture emerges, according to which sharp fluctuations in the climate, acting in conjunction with material culture, accelerated the evolution of our ancestors. It is likely that tools and other technologies allowed hominins to migrate to new environments, even if once in a while, when conditions worsened, these aids no longer ensured survival. This caused many populations to split, allowing cultural and genetic innovations to take root much faster than possible in large groups, and evolution accelerated. The others just perished. And the species that eventually survived, us, won thanks to random events, like those climate changes for example, no less than it won thanks to its talents.

The descent to the ground

Despite the decisive role of material culture in the creation of the extraordinary phenomenon known today as Homo sapiens, it appears relatively late in the story of our development. More than four million years before our ancestors learned to use tools, they had to stop living in the trees and try to live on the ground, a difficult transition from an ape with four limbs designed for grasping. This required a monkey that was already used to holding its body vertically and supporting its considerable body weight with its arms as much as it did with its legs. Indeed, it is known that this posture appeared in some of the first hominoids, members of the family to which apes and hominins belong.

The abandonment of trees underlies the enormous changes in our anatomy. But while it undoubtedly set the stage for later adaptations in our lineage, it alone did not increase the evolutionary pace of events. About five million years after the appearance of the hominins, they developed similarly to any successful group of primates: from the beginning, the genealogy of the human family was branched, meaning that many species appeared at any given moment, and all of them explored the inherent potential of walking on two feet. Reality shows that these early experiments did not have the power to bring about substantial changes; At that time all hominins seemed to be variants of the same subject in terms of where and how they lived. As befits creatures adapted to life both among the trees and in more open habitats, the brains and bodies of these early human ancestors remained modest in size and retained the old body proportions: short legs and arms with great freedom of movement.

The rate of evolution began to increase considerably only after the appearance of the genus Homo about two million years ago. However, material culture, in the form of stone tools, was born at least half a million years before our first appearance. This strongly supports the idea that culture helped drive the rapid transition from a stable sequence of tree-dwelling apes to a rapidly changing series of ground-dwelling humans. Scientists have found primitive stone tools in Africa from 2.6 million years ago, and there are even earlier signs of notches in the bones of animals carved with tools. We know with almost certainty that early hominins were already making these simple tools, small, sharp stone fragments from fist-sized stone cores.

Despite their anatomy, which originates from an earlier era, the first tool builders had already gone far beyond the realm of consciousness of the ape. Even after much training, today's apes are unable to figure out how to hit stone with stone to intentionally extract a chip as early hominins did. One of the uses of these chips was cutting up carcasses of herbivorous mammals. This radically new behavior shows that the hominin diet expanded rapidly, from a predominantly vegetarian diet to a greater reliance on animal fat and protein, although we do not yet know whether at this stage they were actively hunting or scavenging. Later, this rich diet supported the growth of the energy-hungry brains of the species belonging to the genus Homo.

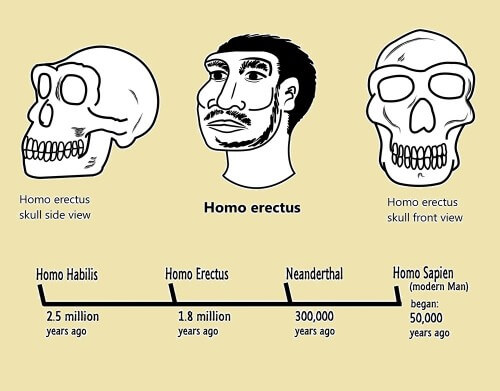

A fierce debate rages among biologists as to which fossil is the first embodiment of the genus Homo, but they agree that the first hominins whose bodies had similar proportions to ours appeared less than two million years ago. Around this time hominins migrated from Africa to many places in the "Old World". These individuals who walked like us, with a wide stride and an upright stature, lived in an open prairie, far from the protective forest, and most likely fed a diet rich in animal ingredients. The brains of the earliest homo species were not much larger than those of the first bipeds, but by a million years ago, various homo species already carried brains twice their size, and by 200,000 years ago they had already doubled in size again.

Arms race in the ice age?

This growth rate of the brain is amazing by all accounts, and it characterizes at least three separate lineages within the Homo species, that of Homo Neanderthals in Europe, that of Homo Arctus in East Asia, and ours, that is, of Homo Sapiens in Africa. These parallel trends also show that the large brain provided a survival advantage to the species, and that brain enlargement was a common trait in the genus and not unique to the particular lineage that led to Homo sapiens. It is not impossible that this tendency led to a sort of arms race, since the adaptation to the use of ram weapons made the human species groups the most dangerous predators to each other, while competing for resources.

The traditional explanation, favored by evolutionary psychologists, for the rapid development of the brain in hominins is called genetic-cultural co-evolution. The process involves a consistent operation of natural selection, generation after generation, with a strong positive feedback between innovation in the cultural and biological fields. As individuals with big brains prospered over the generations, the population became smarter. And so she produced tools and other inventions that helped her adapt even better to her environment. In this model, the built-in interplay between genetics and culture in a single, gradually changing lineage of species required human ancestors, in effect, to become intelligent and develop more complex behaviors and prepared them for more rapid evolutionary change.

But if you think about it a bit, it seems that there were other factors. The difficulty with this scenario is assuming that the selection pressure, constraints to which the species have adapted, remains consistent over long periods. But in practice, the gay species developed during ice ages, a time when once in a while the ice caps spread and reached as far as northern England and even where New York City is today in the northern hemisphere, and the equatorial regions knew very cold periods. In such an unstable environment, there could not have been consistent selection pressure in one direction. The more we know about these climate fluctuations, the more we realize how unstable the environments our ancient ancestors lived in were. Drilling cores of ice from the poles and mud from the bottom of the oceans reveal that the pendulum of relatively warm periods and much colder periods became more acute starting 1.4 million years ago. The hominin populations therefore had to respond to the suddenly changing conditions in each and every region.

Another difficulty of the usual explanation is related to the material findings themselves. Instead of a pattern of technologies becoming more and more sophisticated at a uniform rate over the last two million years, the innovations seem scattered and very separate from each other. New types of devices, for example, appeared only once every hundreds, thousands or even a million years, and in between were hardly perfected. During these periods, it seems, the hominins responded to the environmental changes with new uses for the old tools, and not necessarily with the invention of new tools.

What further undermines the idea of gradual evolution is the lack of evidence that the cognitive processes of the hominins gradually improved at a uniform rate over the years. Even when the larger minded gay species appeared, the technologies and the old way of life remained. New ways of doing things usually appeared gradually, not with the appearance of a new species but during the lifetime of an existing species. The most striking example is the fact that evidence for a distinctly modern symbolic consciousness emerged quite suddenly and only at a very late stage. The first distinctly symbolic objects, two sanded ocher (ocher, earth with a reddish or yellow tone) plates with engravings of engineering shapes, were discovered in the Blooms Cave in South Africa and are about 77,000 years old, much younger than the first Homo sapiens remains that are clearly identified by anatomical signs, which is about -200,000 years [see box above]. Since these shapes are very ordered, the researchers are quite convinced that they were not drawn at random but represent some information. Such sudden breakthroughs do not characterize steady intellectual progress, generation after generation.

The power of small populations

It therefore appears that there is no point in looking for the explanation for the rapid changes that occurred in hominins during the Ice Age in processes that occurred within certain lineages. But it is possible that the same elements involved in the version of genetic-cultural development, selection pressure and material culture, play a role in other explanations as well. It is possible that they simply had a different effect from the one described in the conventional explanation. To understand how the interactions between these factors triggered evolutionary changes, we must first understand that only a small population can assimilate significant innovations, whether genetic or cultural. The genetic inertia in large and dense populations is simply too strong to be consistently deflected in one direction or another. In contrast, small and isolated populations are easy to differentiate.

The human population today does not migrate, it is huge and continuously spread over all habitats in the world. But during the Ice Age, hominins were mobile hunter-gatherers who lived off what nature offered and were scattered in small, far-flung groups throughout the Old World alone. Climate change has repeatedly beaten these tiny local populations. Fluctuations in temperature and humidity and even in sea and lake levels greatly affected the availability of local resources, changing vegetation and prompting animals to migrate. Many places became difficult and even impossible for hominins, until more favorable conditions prevailed.

A million to half a million years ago, hominins already possessed a variety of technologies, from making tools and cooking food to building shelters, which allowed them to utilize their environment more efficiently than earlier species and to overcome purely physical limitations. These technologies must have allowed Ice Age hominins to expand their habitats considerably. In good years, technology allowed hominin populations to spread and occupy areas at the edges of their domains, areas that without these technologies would have been inaccessible. But when the climatic conditions worsened, as happened once in a while, the culture surely gave only a partial answer to the external difficulties. Because of this, many populations must have been reduced in size and dispersed.

The small and isolated groups that were created were characterized by ideal properties both for the fixation of genetic and cultural innovations and for further differentiation. When conditions returned and became favorable, the populations that underwent these changes spread again and met each other. If there was real differentiation, it is likely that competition and selection forces eliminated the weaker ones. If partial or no differentiation occurred, it is likely that the populations merged and the genetic changes were assimilated into the united population. Either way, the changes happened.

Under the frequently changing conditions of the Ice Ages, this process probably repeated itself many times in rapid succession, paving the way for extremely rapid evolution, which material culture eventually accelerated even further. In the midst of the "battles" we were left alone. The cheap combination of cognitive innovation, cultural innovation and climate change benefited us and allowed us to eliminate our hominin competitors or simply survive where they became extinct throughout the Old World in an incredibly short time. Our advantage over the competition was most likely our acquired ability to think in symbols, allowing us to weave plans and plots in ways never seen before. It is interesting to note that this development probably only occurred in the days of our species, Homo sapiens, and was probably spurred on by a cultural stimulus, probably the invention of language, which is the ultimate symbolic activity.

This view of our evolution, in which our miraculous species, by all accounts, emerged from a rapid succession of external events independent of the traits that distinguished the species from which we evolved, is much less flattering than the traditional idea of elegant improvement over the ages. But a careful examination of the result clearly confirms it: it is not necessary to look too deeply inward to see that, despite all its impressive features, Homo sapiens is a species with many flaws, a topic on which reams of research has already been written, many of them by evolutionary psychologists.

And yet, viewing our amazing species as an evolutionary accident carries a deep lesson. Because if evolution did not shape us as something specific, tailored according to the dimensions of its environment and purpose, then we have a different freedom of choice than other species. We can decide how to behave. And this means, of course, that we must also accept responsibility for these decisions.

- in brief

A new theory credits early man's extraordinarily rapid rate of evolution to a combination of cultural developments and unexpected climate change. - Climate change repeatedly caused the fragmentation of hominin populations into small groups where genetic and cultural changes quickly took root, accelerating diversification.

- Our species, Homo sapiens, which is anatomically distinct from other human species, was born in one of these events in Africa about 200,000 years ago.

- About 100,000 years later, an isolated group of the species acquired the ability to use symbols. It is almost certain that this unique symbolic consciousness is what enabled the elimination of all the hominin competitors in a short time.

About the author

Ian Tattersall is a retired fossil anthropologist and curator of the United States Museum of Nature in New York. His research deals with hominins and lemurs, and he often writes about these two groups of primates.

A history of innovations

The group of hominins, to which humans belong, has undergone far-reaching anatomical, behavioral and cognitive changes in the last four million years. At the beginning of the period, the ancestors of the tree-dwelling group began to try a more terrestrial way of life. About 2.6 million years ago, primitive stone tools already appeared; Cut marks on the bones of mammals show that hominins began to dismember corpses even earlier than that, opening the door to a growing dependence on animal protein. This dietary change ultimately fueled the increase in brain volume after the emergence of clearly identifiable representatives of our species, Homo, about two million years ago.

More on the subject

Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins. Ian Tattersall. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

21 תגובות

pay attention:

Just as cultural developments and unexpected climate changes caused a rapid rate of evolution.

And just as it was an isolated group that acquired the ability to use symbols that enabled the elimination of all hominin competitors in a short time.

In the same way, not external but internal climate changes among us will cause the rate of evolution to accelerate. A person will turn from a single item into an environment. Yes he will be an environment/network, an integral person with upgraded consciousness and enhanced abilities.

And in the same way acquiring symbols (Young called them archetypes), there will not be external symbols but schemas built within us that will allow us to communicate with each other on a different level.

One can write down a philosophy, one can write down a broad imagination, but rather changing the object of research from the investigation of something external to the investigation of the inside of man will slowly be revealed as one that will reveal an innovative approach to the question of our existence.

Absolutely miracles. I agree with you.

more luck than brains.

You are lucky….

My wise angels….

It's all luck. There are probably some who were blessed with a little less...

He wanted to say that he disagreed with himself

Well, what did you mean by that?

Raphael

There are 100 million sperm cells in one ejaculation. That is, the chance that a certain person will be born, given that his father exists, is one in a hundred million. If we start with the grandfather - the chances are one in ten thousand trillion... and if we continue another generation - one in one trillion trillion...

So each of us is incredibly lucky to be born, isn't it?

But, pay attention - if you take a cup of salt and pour it on the floor, the chances of getting this particular dispersion of the grains are much lower!!

To the illusory creature with a thousand names who now calls himself "the angel Raphael" - all in all I reinforced what Nissim said, what's wrong?

Raphael

Although you are called by my name, you shame me. Looks like you haven't gotten over your bullshit yet.

how do you say

If it wasn't this it'd be something else

The difference between the luck that we are here specifically and the luck that something else was there. Overall average for all possible universes and creatures, not so much luck.

The big bang - luck. The amount of anti-matter versus matter - luck. The creation of life - luck. The whole process of evolution - a lot of luck. How lucky we are!

anonymous

You summed up the article nicely - we are here, very much, by luck.

יוני

Forget everything Harari says. He is eloquent but not an evolution expert (I think he is a historian by training).

Almost every important opinion of his is taken from the words of the experts really, look them up directly. His interpretation will only add to the confusion, that is, not everything he says is wrong, but it is a second-hand explanation.

It is likely that the more food was available, the more time there was to develop ideas, on the other hand, each development of ideas increased the availability of food. But how things actually worked is hard to know.

About 75 years ago, the Spines were almost exterminated, according to the findings, this is even though we were as smart then as we are today. The advantages did not help, luckily we survived.

One of the theories assumes that the great leap in our ability to become "rulers of the world"

It resulted from the domestication of fire and a shift to cooked food, which caused more energy resources to be directed to the brain than to the digestive system, which had to invest a lot of energy

In digestion raw food of all kinds (raw meat, raw vegetables and more)

According to one of the theories I heard in Dr. Harari's course

is where our problem is

Thanks for the "in brief" section

Asaf

It reads: "A new theory attributes the extraordinarily rapid rate of evolution of early humans to a combination of cultural developments and unexpected climate change."

Does that sound like "bullshit" to you? It makes a lot of sense to me. We also know of other cases where environmental changes caused rapid development, not only in humans.

Miracles, Shaul's intention is that since the climatic changes affected all animals as well as humans, it is strange that only in humans they caused brain growth and in sister animals no change is seen.

By the way, the article still does not update much because 100,000 years ago Homo Sapiens was not smarter than Neanderthal, only 70,000 years ago we suddenly got a mind and with its help we destroyed all the other hominids very quickly. The article does not explain that.

borrowed

based on which you assume it? Do you know of a similar case from which you derive this?

According to this theory, there should be at least a few dozen other evolved species that went through exactly the same processes under the same conditions.

In short - another theory that is nothing more than bullshit

In any case, the same evolutionary development, passed from parents to their children for hundreds of thousands of years.

Hence, the same change that is inherited from the fathers, takes place until the moment when the egg of their sons is fertilized,

However, the development takes place in the fathers throughout the life period. Even after fertilization of the egg.

Therefore, it seems that the acceleration of evolutionary development is affected by the phenomenon of having offspring

at an older and older age of their parents over the years.

Perhaps there is a correlation between the average age of the birth parents, and the slight thinning.

The hominins lost their strength, their speed, and their ability to climb trees, due to an easy life and a lack of predators.

And just as a blind person makes more use of the sense of hearing, so the physical defects caused the brain to be overused for survival, when the conditions changed.