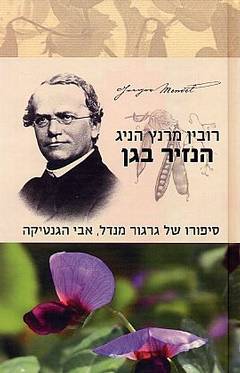

The Monk in the Garden was published by Dvir and translated by Emanuel Lotem. This book joins the books "Brunelsky's Dome" and "Galileo's Daughter" which beautifully describe the history of science

By: Robin Merentz Hennig

Chapter 10

Leaves begin to turn yellow and brown. Flowers are made

seeds. Everything is soft, big, ripe. I walk among the plants,

And they reflect my mood - contentment and contentment.

The tireless gardener. Lauren Springer

The autumn garden was taking on twilight hues, and Mendel felt like collecting the last of the pods. In a short time it would get dark, and he was forced to hurry - a situation that was much to his displeasure. Much more than that, the slow movement between the plants suited him, which he enjoyed calling them "his children" to test the reactions of guests who didn't; They knew about his experiments in horticulture. "Please

to see my children?” He would ask the priest who had taken a vow of celibacy. The look of astonishment and embarrassment that appeared on their faces was always ridiculous. If you had heard Gregor Mendel tell his story himself, you would have thought that at the time he turned evening in the fall of 1862, he had not yet fully prepared the truths of heredity that his small and surprising children - and their relationships with their parents, siblings and descendants - were still watching with such cunning. Like any good parent, he watched over his garden peas for six long years, gathering their pods, extracting their seeds, dividing them into piles according to their colors and shapes, following their height and the colors of their flowers and the flowering habits they exhibited from growing plants. But like any parent, he still didn't really understand his children. True, he spent his leisure hours during these six years in deep contemplation of the oddities and idiosyncrasies of . Pisum.

As a way that a parent may examine, with affection and concern, the outgrowths of his beloved loins. But the scientific significance of all these observations began to dawn on him only now. At least, that's how he would tell - after the fact, in the methodical way that made him such a good teacher - how he gradually began to understand the laws of inheritance. In his story, his thought processes seem more sterile and direct than they were in practice, obviously. Like other scientists, before and after him, Mendel imposed on his Pisum studies a narrative that does not fully express the real excitement that was embodied in them. Perhaps the story becomes a little clearer because of this, as if his thinking was so logical and so pure that it can be seen as necessary and inevitable.

But what he lost, it seems that he would have gained more: the opportunity to present the truer and more fascinating nature of the experimental work, as a mysterious, tortuous and confused occupation.

Well, Mendel's reconstruction of his research probably modified the truth to some extent - and in doing so, underestimated the value of his own inspiration and foresight. Since he was well versed in physics and hypothesis testing, it's hard to believe that he didn't know what to expect from his peas at every stage, and why. Of course, as the years go by, while the results accumulate little by little. Some of his hypotheses have changed. But it was a false pretense, when he claimed - and begged us to believe - that he did the work of gardening first, and sat on things in depth only later.

He turned in his thoughts under the dome of the sky, in his garden, or behind closed doors, in an armchair that stood in one of the alcoves of the library, with an open book on his lap. Sometimes he sat and thought in the orange grove; And sometimes he went up the stone steps behind the greenhouse to the second stand of the monastery courtyard, where his beehive was found. When the pea experiments began requiring less gardening and more contemplation, Mendel spent more time with his bees, as this had been his hobby in his youth - beekeeping and honey production. Years later he tried to multiply bees to verify unity

from the results he got from his plants.

With age, Mendel began to underestimate the climb up the stairs to the beehive, as he found himself, in his own words, "blessed... with an excess of size and weight that makes it very difficult for me to climb the hill, in a world governed by universal gravity." But the view alone was worth the trouble of the climb. The red tiled roofs of the monastery, the basilica tower, the towering hill on top of which Spielberg Castle was perched, the bustling streets of Brin, spreading out from the Klosterplatz in all directions - this view gave Migdal an opportunity to think, to rest his darkening eyes, and on the worst days, to renew his sense of mission and remind himself of how important to continue his work in the garden, in spite of all the frustrations and difficulties.

By 1862, the view over the monastery hill was perhaps the widest Mandel had seen in his day. If we ignore his trips home to Heizendorf, or his appearances in Vienna - some of which were wonderful and exciting, and some of which were tinged with bitter disappointment - Mendel remained confined to his home, in fact, for the first forty years of his life. But in the summer of 1862 he went on a long trip abroad, and it filled him with an eagerness to travel that remained with him until the end of his life. Mendel, along with other teachers at the Reali School and with its principal Yozef Oshfitz, was a member of the official delegation sent by Karin to the first annual international exhibition in London - a technological showcase, to which the Reali School contributed a presentation

in crystallography.

The exhibition was huge. It was held ten years and more after the London Exhibition of 1851, the first international fair in world history. The most famous legacy of the first exhibition was the magnificent Crystal Palace, Crystal Palace - a huge building with curved roofs of steel and glass, a work of architectural sabbath, because it was the first prefabricated building of its kind. The exhibition of 1862 put the emphasis on technology and not necessarily on art, and everything that was in it was done on a spectacular scale. Although the exhibition hall was not as beautiful as the Crystal Palace, it was the largest of its kind built up to that time, about 400 meters long and 190 meters wide, and covered about seventy dunams. Close to ten thousand people applied and asked for space for the exhibition: at least seven times the number that the huge building was able to accommodate. The most imaginative proposals were offered by hobbyists: perpetual motion machines; the oldest slice of bread in the world (from 1801); Epic poetry houses to be hung in the photo gallery; shoes equipped with springs; mustache guard for soup eaters; And the mummified body of a certain Julia Pasterna, a bearded woman from Mexico who was presented, in one of the curiosities that have sprung up like mushrooms after the rain since the origin of the species appeared as "a figure in darkness that was divided by a man, by an orang-utan". An accountant from the City, the abode of the more buttoned-up of London's businessmen, proposed three inventions that could hardly be described as buttoned-up: a self-activating toilet, an improved theodolite (an instrument for measuring horizontal and vertical angles that serves surveyors), and a "multi-flute Tony" who has the power to make every sound that the human ear can hear. A bookbinder proposed a plan for a hanging mechanism for bridges and elevated roads: an insurance agent came up with an improved method for making wine. A nursery owner came up with ideas for improving surgical instruments, and a surgeon proposed a device to hang on the wall designed to simulate the healing of fruits.

The official exhibitions presented by the countries of the world were subdued compared to all these. The man who asked to fly inside the glass dome, which is over eighty meters high, was turned away, but the representatives of the various nations were allowed to fill the space of the hall with dozens of exhibits tied to the ground, demonstrating to the praise of their most important industries. Austria introduced merino wool, leather goods, lactic acid candles, dyed fabrics and thoughtfully carved pipes, alongside a mountain-climbing locomotive. She also offered a demonstration of the process of producing tin from scrap iron, and demonstrated the variety of foods, fabrics and paper products that can be made from corn. A similar tone of praise characterized the exhibits of all the participating countries, about two dozen in number. It is possible that the London exhibition was devoid of surprises of any kind, but the mayors of the city of Breen found in it a unique opportunity. Brin was a center of industrial activity (mainly textiles), a center for an active and vibrant economy. The city's fathers believed that if they wanted to ensure the continued rising prosperity, they should invest in projects of increasing technical sophistication. One of their ideas was the establishment of a chnological museum - and at the London exhibition they, or their emissaries, could learn how to plan such a thing.

When Mendel participated in creating the presentation of the Realist School, did he realize that the logic of crystallography could help him understand the meaning of the numerical relationships he derived from his peas? Did dealing with crystals lead him to the conclusion that nature is based on discrete properties? Did the crystals serve Mendel, in one way or another, as a template in which his growing understanding of his dizzying collection of numbers - numbers of peas, of pods, of plants - was cast as he tried to place them in some algebraic expression. Phrase

to express the logic of heredity?

The crystals that Mandel was dealing with now, like the hereditarily mixed units, reproduce themselves. In both peas and crystals, seemingly motionless particles are capable. As it turns out. perform one of the most central functions of living beings. The shape of the existing crystals defines the shape that a new crystal can take, limits the range of possibilities, serves as a pattern. In a similar way, although Mendel probably didn't know it yet, 'the dictates of the traits he tested as peas also limit their possibilities. Apon can be round or angled, but not in the middle of the road; tall or dwarf. But not anything else. In some important and yet mysterious way, the attribute dictates keep all things within narrow limits, just like the crystalline structure, limiting a creature's ability to be different from its ancestors.

"To London, to London, to see the Queen," sang the words of a common children's song in those days, and it is believed that Mandel was fascinated by this trip abroad as much as the child in that song. Almost no documentation remains from that mission, but we have a photograph of the fully assembled group, over thirty people, standing in front of the Grand Hotel in Paris in one of its parking lots before crossing the canal. A short time later, the magnificent Parisian Opera building was to be built near the hotel. The photograph shows over thirty men and a woman friend. Arranged in photo poses on the steps of the hotel, and palm fronds hover above. And here he is Mendel, standing right in the center of the group and sending his gaze somewhere over the photographer's left shoulder. Mendel, the only one who wore glasses - and almost the only one who did not flaunt a bushy mustache or a full and rounded beard - did not reveal that he was a priest. He wore a morning jacket, like everyone else, with a white shirt and a black bow tie. He is not smiling in the photo. And even if some of the men lean against each other or put an arm on their neighbor's back, Mendel stands upright and alone.

The group first lingered in Vienna, a city Mandel had come to know well during his student years. This visit must have evoked some memories, both of the days of happiness that flowed through him in absorbing new knowledge on every scientific subject that occurred to him, and of the despondency that fell upon him when he failed - and failed again and again - in the friendship exam that he had once considered. There were several other Austrian and German cities on the way to London: Salzburg, Munich, Stuttgart, Karlsruhe and Strasbourg.

The journey lasted about three weeks in total, from July 24 to mid-August. Some have argued that it is possible that Mandel, or one of his compatriots, met with Charles Darwin during the visit. How refreshing is the thought of such an imaginary encounter. "I do not understand the mechanisms of the process of natural selection," Darwin would confess, in his lame German or through an interpreter. (Mendel, who as a child spoke Silesian German, wrote in formal German and taught in Czech. He did not know a word of English.)

"Yes, of course, I insisted on that when I read your Origin of Species," Mendel would reply. He read the book in its German translation, as soon as it appeared in 1860, and heard a lot about the controversy that arose from his writings, both in conversations in the monastery and in the lectures of the Society for the Study of Nature. He devoured Darwin's book, penciled notes in the margins, in his small, meticulous handwriting, and from time to time revealed the intensity of his feelings by emphasizing with a double underline, or even an exclamation point.

Although Mendel agreed with Darwin's view in many ways, he disagreed with the basic logic of evolution. Darwin, like most of his contemporaries, saw evolution as a linear process, always leading to a better product. He did not define "better" in religious terms (in his eyes, a more developed animal was no closer to God than a less developed animal - the ape-man had no advantage over a squirrel) but in an adaptive sense. The ladder that creatures climbed during evolution always led to a better adaptability to the constantly changing world.

If Mendel believed in evolution at all - and this question is still highly disputed - it was evolution taking place in a finite system. From the very distinction that a certain characteristic feature may be expressed in one of two contrasting ways - round or angular peas, tall or dwarf plants - a restriction was implied. Darwin's evolution was completely open; Mendel's evolution, as any good gardener of his time could see, was closed. And it is important to note that neither of them saw the finger of God in the process of changing the species.

Mendel, like the geneticists who were to follow the path of Scheppels, questioned the blended inheritance that Darwin believed in. "I do not believe that fusion can be used as an explanation," he might have said in that imaginary meeting between the two scientists in London. "According to the laws that I am going to reveal now, or at least the laws as far as they concern Pisum, properties do not merge. They remain solitary and move on in a bride-dependent manner."

"I'm actually glad to hear you have an alternative explanation," Darwin might have admitted. "I'm tired of hearing the critics of Shiv and Dashim on the issue of flooding. Well, tell me - what do you know about how adaptations are preserved?"

But it is hard to imagine that such a meeting actually took place. Even if we had accepted the explanation, which is extreme in itself, that Mendel would have wanted to meet with the greatest biologist of his day, there would have been more pressing matters preventing its existence. While the delegation from Breen was in town, Darwin's son, twelve-year-old Leonard, fell ill again, and his parents stayed with him at their home in Down and refrained from receiving guests. It was a terrible experience for the Darwin couple, who lost three children: two in infancy and another, ten-year-old Annie, just a year before. But Leonard remained alive - and even reached old age and returned, because he turned ninety-three years old before his death. He was the only one of Darwin's ten children who got to see how Abir's work became the foundation of a completely new way of thinking, not only in biology but in all of modern science.

In the autumn, when the journey to London was over, Mendel returned to Gnu. He went back to tending to his peas and working out his calculations - the ones he said were the most difficult, in all his experiments up to that point.

Mendel's monohybrid and dihybrid hybrids meanwhile reached at least the third generation (that is, what we would label today 4F). Some of those first hybrids still thrived in his garden, and their genealogies were carefully documented down to the sixth generation. And now, at this hour of dusk on an autumn day in 1862, Mendel completed the fourth generation of his most ambitious hybrid, the trihybrid. It was a cross between dominant and recessive parents that differed from each other neither in one trait nor in two, as in his previous monohybrid and dihybrid hybrids. The new hybrids "crossed" plants that differed from each other in three separate characteristics: the shape of the pea, the color of the pea and the color of the seed coat.

* The article was published on the old site when the book was published in 2003, with the help of the publisher, and was re-uploaded as part of the database migration project