A book on and a book on ("Haaretz Books" 17/06/98)

Following Jack Miles' book "God - A Biography"

Jack Miles, an American lecturer and literary critic, reads the Bible. His main innovation is the presentation of God as the main hero of the Bible, a hero who has problems, difficulties, successes, disappointments, anxieties, crises and failures, who has different and developing characters (creator, destroyer, friend, redeemer, lawgiver, master, conqueror, father , executioner, saint, wife, counselor, guarantor, sleeper, observer, and more). In short: biography.

On the one hand, the book has an amused, off-the-wall, prickly, teasing aspect. On the other hand, he has a serious attitude, because Jack Miles is, as mentioned, a literary critic and a lecturer at the California Institute of Technology. As for the provocative and taunting side, it seems to me that it is not randomly scattered in the book, but rather it is principled. In the very title "God - biography" there is a provocation of the basic intuition, according to which the concept of God belongs to the eternal, absolute and transcendent and not to matters such as frustration, ambitions, successes, failures and biography.

I don't have much to say about the hanging and teasing side. Partly because the answer to the attack is the attack against me, and I don't have the talent for that and this is not the stage; And partly out of respect for the subject, I would like to return it to what it is - the most serious subject that a person is capable of dealing with.

On the other hand, I would like to comment on the serious claim behind the book: that it expresses a reading of the Bible as literature and not as theology, that is, a reading of a literary critic in the creation of literature. I have two questions about this project. First on himself, and secondly on the performance.

First, to the project itself. It is unthinkable to try to taste sounds or touch light. For each type of reality the sense organ corresponds to it: the eye corresponds to the light, the ear corresponds to the sound, the touch corresponds to the material.

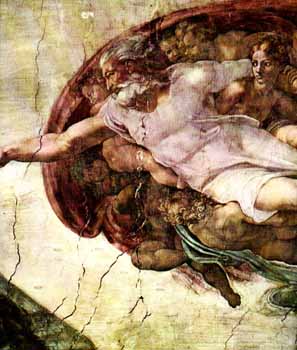

And so in spiritual realities. Perhaps you can try to read "Hamlet" in historical categories: is it true or not true that Denmark had a royal court structure like the one described in the play? Was there such a royal dynasty and was there such a prince? Hamlet can also be tested in psychological categories. Was Hamlet neurotic or had another disorder? As we know, Freud tried to analyze a painting by Leonardo da Vinci according to the subconscious contents encoded in it.

There is a certain interest in such attempts, but they would be grossly missed if we do not continue from here to the main category in which "Hamlet" is written - which is the artistic, the aesthetic. Because in the work of art, both the historical and the psychological material are processed and shaped to serve the aesthetic super level.

At this level we talk about structure, development, rhythms, and the meanings emerging from the whole. True, there are no fixed reading rules, and each work determines its own reading; But forever the artistic-aesthetic level processes and shapes all the other levels.

Thus, attempts to read Hamlet on a historical level or see Leonardo's works on a psychological level are no more wise than trying to touch or smell them. But the difference between the physical senses and the spiritual categories is that the physical senses are given to us from birth, while the spiritual categories develop. The scientific, psychological, and certainly the artistic categories also need training and development.

Of course, the Bible can also be read as a historical report, as a psychological essay or as a literary work. But if the reading stops at that, again it is no better than tasting a painting. After all, in the Bible, both the historical, the psychological and the literary foundations serve as the super category, which is faith. The Bible is not science, nor history, nor literature, but is a religious document. And not just any religious certificate, but the original document from which people, including members of other religions, learned what religion is in general - as distinct from mythology or a mystical method that can be known from other sources.

And just as the Bible was written from a religious point of view, so a person has a category of perception suitable for receiving the message. He must, of course, agree to activate it, and also train and develop it (as in the factual-scientific category and the aesthetic category). This is of course not a simple agreement but a binding, existential choice. So, reading it in the Bible will not be done only through

The literal construction of the words, as Miles makes sure to do, but never out of an existential listening to beyond them.

On the religious level, man devotes his entire being to call upon God as a living and existing reality, animating and sustaining, and not as a literary hero, that is, to absolute reality, the source of all reality. Because of this, the reading in this way always strives beyond any known and familiar content, beyond any existing system of meanings, to what has not yet been expressed and in fact cannot be finally expressed at all.

The Jewish people engaged in such a reading intensively for thousands of years, and the result is the addition of insights, interpretations and meanings from generation to generation. Of course, it is not at all possible to compare what one understands when reading at the level of existential commitment to what one perceives in another way of reading - literary, geographical, folklore or curious, amused or clever or teasing.

But another puzzlement is what Miles reads even in his capacity as a literary critic. Allegedly, the Bible contains stories about creation, about man, and especially about one nation - the nation of Israel, who is the collective hero of the book (in fact, there is very little about God in it: unlike mythology, whose main focus is the opinion of the gods, the Bible is mainly concerned with in man, and does not tell us about God but the modes of his relationship to man).

But actually, the Bible is not at all a book "about" something; He is not even on man or on the people of Israel; It is a book "to" someone - to man, to Israel. It is a creator, worker, mitzvah, lawgiver book. The stories "about" are also nothing but another, more indirect way of speaking "to": they are introductions, frame stories, illustrative stories for the main thing: speaking to man. The Bible, so to speak, is not written in the past tense but in the imperative tense.

Indeed, the Bible worked and created, and participated in the design of cultures and religions. One may not like the message, one may reject the commandment, but one cannot say that it is a book "about" something; Certainly not "on" God. You don't have to accept the commandment to understand the mode in which the book is written, or rather, speaks to you. And isn't this the essential difference between Greek-Western literature and the Bible. Greek literature is always looking, telling, describing. And so it is also in Greek philosophy: it is theoretical, observing. Aristotle saw the fulfillment of human potential in the life of contemplation. On the other hand, the Bible is not a description of what is found but a commandment and guidance to what is desired. In Kantian terms, Greco-European literature is the literature of the is. The Bible speaks in the mode of .ought

Miles forces the Bible into the bed of Sodom of Modus not to him, into a narrative genre and actually mythological. He turns the Bible into a myth, telling about an idol in the name of God and the fascinating stories of his life. And the Bible, needless to say, is dedicated to the fight against idols even if the idol is one and only.

This, by the way, leads Miles to a typical mistake. He entitles the entire chapter about Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi with the title: "Wife". The Creator appears here, so to speak and in an exceptional way, in a female role, as a wife; And about the so-called feminization of God, brilliant and scholarly interpretations appear. But the whole thing is based on a mistake in reading comprehension. In the verses "You shall not commit adultery with the wife of your youth, for she is your friend and the wife of your covenant" there is no intention to betray God, as Miles interprets out of routine. All the verses there speak simply against the spread of the custom of dismissing women easily, and the betrayal is the purely human woman, "your friend and the wife of your covenant". Miles forgets that the Bible is first and foremost Torah, that the prophet deals with human life, not the divine.

But apparently Miles does not intend at all to give us a true or in-depth picture of the Bible. It seems that the main thing in the book is the brilliance, the surprise, the teasing. Maybe that's how literature is read today, but if so, it should worry not only those who take the Bible seriously, but also those who take literature seriously.

Because today, the central status of the book in Western culture is being eroded twice: from the technological side and from the theoretical side as well. On the one hand, the status of the book has been eroded by electronic media, which means more visuality, more interactivity and, in short, more "user-friendly" immediacy, in contrast to the theoretical, distant and effort-requiring abstraction of the book. Marshall McLaughlin welcomed, already in the previous generation, the decline of the "linear" book and the rise of "simultaneous" television, etc. Even the "book" itself, which the book lover would take down from the shelf with reverence and cherish it with love, can now be "downloaded" from the Internet, in its entirety or in parts, disassembled and assembled according to taste and desire and without any additional restraints.

On the other hand, the value of the book has been eroded by contemporary critical theory. She no longer believes in a stable meaning for words, for language. It no longer accepts the pursuit of the "truth" at the heart of a literary work. As we know, reading a book is seen today not as a pursuit of truth but as an opportunity for personal creativity. The "meaning" of a work of art thus becomes a kaleidoscope of interpretations and viewpoints, which are ultimately arbitrary. In such a climate, it is no wonder that what attracts attention is brilliant, stimulating, sensational, surprising readings. And such readings tend to be quite empty by nature.

George Steiner writes important things about this state of affairs in his books "No Passion Spent" and "Real Presences". "A. The knowledge in particular - the Bible, the Bible. But on the other hand, in our situation today, the very ability to get out of what he calls the "crisis of meaning" we are in and return to meaningful reading, to faith in the meaning of words and literature - requires a deep restoration, as deep as the depth of the crisis. And such a restoration must rest, ultimately and ultimately and despite all the hesitations, on the religious-theological sphere. Literature needs a reaffirmation of transcendence - of the real presence of meanings beyond the text; And such transcendence, in the end, can only find support in the reconfirmation of transcendence in God's knowledge, the absolute presence beyond, that is - and this he writes after countless cautions and reservations - God.

It is understood that the very cautions and reservations, the apologies and detours indicate that with Steiner we do not hear the voice of the Bible, which is the voice of direct and absolute certainty, but the hesitant voice of our century, which does not know any certainty or security and is looking for a foothold for itself. And yet, Steiner returns and turns to the Bible as the book of knowledge, the father model for all matters of reading and meaning, and therefore, literature.

With regard to Steiner as well, it could be argued that he neglects the difference between "on" literature and "to" literature. But here the neglect of the difference is less harmful, because with him there is no forcing of the Bible into a mode of literature but an attempt to use the Bible to re-establish literature. Both literature and the Bible require the activation of the category of the transcendent; In literature, the transcendent is revealed indirectly, through symbolic structures; In the Bible he speaks to man directly. Therefore, the Bible is indeed the basic document for all that matter of the possible connection between man and dimensions beyond him - through the language, the word, the book.

Again: Steiner's reading of the Bible is contemporary - a reading that is aware of doubt and apostasy, that includes the crisis of the absence of God's presence and in a certain sense even relies on him as a starting point - and it is precisely from this that one returns and meets the God of the Bible. It is a hesitant, reluctant, ashamed, embarrassed, wondering, indirect meeting, but it is done out of all the anxiety of the weight of responsibility, fate and risk.

This kind of meeting seems to me to be the most important, significant development of our generation. But it is a modest, almost underground development of individuals, at their own risk. And meanwhile, publicly and with great publicity, what Steiner calls "clever trivialization, amused nihilism" continues. The deconstruction continues, the dismantling of the foundations of culture, the foundations of morality and the foundations of literature, and in this context also the playing with the Bible. Bestsellers are also born here for their short and well-publicized lives.

Israeli readers have nothing new. He already preceded Miles Meir Shalov ("Bible Now", Shoken Publishing). In both cases it is a matter of busting myths, demystifying, bringing the transcendent down to "eye level". Meir Shalev dealt with the heroes of the Bible. Miles came and also made God himself a biblical hero at eye level. But man's eyes are not so low. They themselves are native to the heights. The current climate is one of humiliation. But time will tell if man will agree, or be able, to keep his eyes fixed on the ground, or, with a sigh of relief, return his gaze to the heights.

* Daniel Shalit, doctor of philosophy, composer and conductor, lectures and writes about Judaism and its relationship with general culture. His book "Interface Conversations" was published by Tavai Publishing