Everyone knows that the world is divided into the haves and the have-nots. Those who don't have them are divided into those who don't really care, and those who intensively browse the economy sections and stock market websites to make the move that will put them in the group of those who have.

'The Rise of Money: A Financial History of the World' (published by 'Am Oved', translated by Yair Levinstein) is a book that is also suitable for those who don't have it - but it is especially excellent for members of the second group.

Economics, in my opinion, is a great example of how you can make a successful reference book out of any subject in the world - and no matter how dry and gray it may seem on the outside. On the surface, for those who don't quite like floating rate bonds and loans, economics is one long unchanging yawn. Behind the scenes, however, lie the most dramatic human stories: greed, crazy risks, dizzying successes and terrible failures. Neil Ferguson, professor of history at Howard University, breathes life into this problematic subject and shows us the fascinating sides of it - without giving up in the least the quality of the investigation and entering into the small details. The ideas and stories that Neil chose to focus on in the book maintain a high level of interest almost throughout, while conveying to us some important messages - one might say subversive, even.

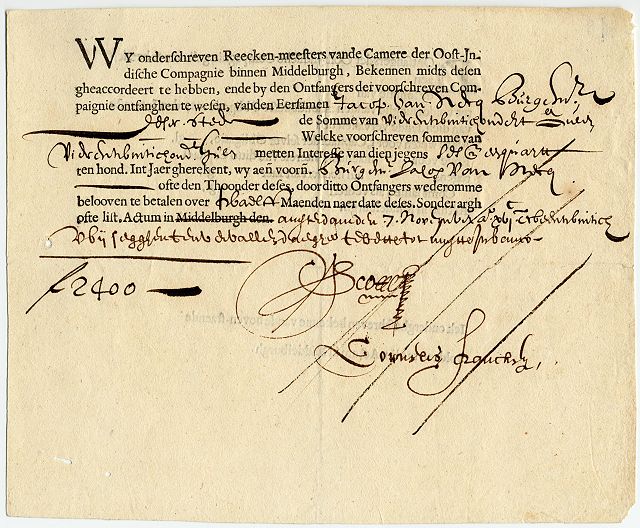

One of my favorite examples from the book is that of the bonds. For laymen (like me) a bond is no different, at least in principle, from any other promissory note or security. This and that owes to him and him so and so. *yawn*

But when you follow the story of the famous Rothschild family, as it is described in 'The Rise of Money', you suddenly get a real idea of how things go behind the scenes and how much we, those who don't have (concept and money) are unaware of the true power of the capitalists.

Nathan Rothschild, the senior financial mind of the family, made his initial fortune by helping the British government: he volunteered to smuggle gold into the European continent, in defiance of the economic embargo imposed on it by Napoleon during his first term. When Napoleon came to power for the second time, Nathan estimated that the upcoming war between France and Britain would be prolonged - and accumulated large amounts of gold in preparation for what was to come. In practice, however, the Battle of Waterloo (this is from the famous 'Abba' song) decided the battle earlier than expected - and the Rothschilds were in a lot of trouble... The war ended too quickly, and they were left with a large amount of gold whose market value was about to drop dramatically.

Nathan bet the whole pot. He purchased bonds of the British government with all the amount at his disposal, even though the reputation of these bonds was very poor and many expected a severe economic crisis in the United Kingdom. Fortunately for him, the British recovered. The price of the bonds soared and Nathan Rothschild became one of the richest - and most influential - people in Europe and the world.

A bond, Neil skillfully demonstrates to us, is extremely powerful when it is in the right hands. Nathan Rothschild and his family bought many bonds of the British government, and later of most of the European rulers: their status as debt holders meant that they were the ones who determined whether these governments could raise funds through the sale of bonds or not. For example, during the American Civil War, the Rothschilds decided not to purchase bonds issued by the South because they did not consider it a sufficiently reliable debtor. The result was the economic starvation of the South, which felt very much the defeat in the entire war... the bond, it seems, is just as strong as the sword..

'The Rise of Money' is a must read, in my opinion, for all stock market enthusiasts who are thinking of taking part in courses and workshops to play in the capital markets. First, he explains in an excellent way all the dangers that lie in wait for investors - the enormous damage of inflation, the ease with which they are sucked into a financial bubble, the true power of those who have capital compared to the nothingness of those who do not - and much more.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, it demonstrates how much economists - however smart and talented they may be - have no real idea about the financial future. Also the Rothschilds, as I described earlier, were only a step away from a terrible financial disaster - and miraculously survived. The crises, the bubbles and the crashes march along hundreds of years of history, and no one has the ability to predict them or (even worse) draw lessons from them that can be applied to the future. It is impossible to finish the book without feeling how distorted is the picture that some analysts and commentators paint in their articles when they claim to predict the future of a commodity, a stock or any other financial instrument.

The book is not without its shortcomings, of course: the two most notable are an extravagance in statistical data and a stinginess in helpful explanations. Ferguson, perhaps because he feels that it is his duty as an academic to prove his claims to the hilt, sometimes exaggerates the amount of statistical and mathematical data he provides us. This is a welcome tendency for an economist, but it sometimes spoils the regular reading experience. Like everything, the secret is in the dose - and here there is a certain exaggeration. Precisely in the places where stopping the flow of the story in favor of a basic explanation would have been useful and helpful - Neil forgets the readers behind. For example, when he tells about the Italian Medici family that used double-entry accounting, I have no doubt that even a novice accountant will understand what it is about - but everyone else probably won't. It is possible, of course, that 'double-sided accounting' is not important enough in the story to warrant an in-depth explanation - but in that case, this term should not have been there in the first place and should be abandoned altogether.

Nevertheless, this is an excellent book even for those who are not well versed in economics. The vast majority of the explanations are clear and fluid, and the insights provided by reading are priceless for any mature person in modern society. A book worth every penny, share or bond you invest in it.

[Ran Levy is a science writer and hosts the podcast 'Making History!', about science, technology and history. www.ranlevi.co.il]

8 תגובות

For anyone interested, the series "The Rise of Money" is all on YouTube - 6 episodes.

Here is a link to the first episode. The rest of the chapters are linked to it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BKS6-MRj5r0

Ran, thanks for the review.

Don't treat frustrated people like 4.

Money does not indicate what is there, but rather where there is not...

Money does not point, but there is, but precisely where there is not...

It is interesting to read how Ron himself writes that he does not understand economics and the whole issue of bonds causes him to yawn and hiccup, but a sentence later he can testify that this book is no less a "must have" book than that.

In order to comply with the "academic" rules, I will quote below:

1. For laymen (like me) a bond is no different, at least in principle, from any other promissory note or security. This and that owes to him and him so and so. *yawn*

2. The rise of money' is a must read, in my opinion, for all stock market enthusiasts who are thinking of taking part in courses and workshops to play in the capital markets.

In addition to this, I really liked Ran's devotion to academic writing, a devotion that forced him to write the entire paragraph that begins with the sentence "The book is not without its shortcomings", which he continued with another paragraph that begins with "However, this is an excellent book even for those who are not well versed in economics" .

Many thanks to you Ran, really your lecturers in the academic writing department can be proud of that..

Ren, I liked your review of the book and hope to read it soon

Thanks

Leave the book and the mini series is truly phenomenal

There is a famous experiment in which they investigated how much students would agree to pay for a NIS 20 bill with certain game rules. It got to the point where they paid almost NIS 30 for a NIS 20 bill....

In any case, the main idea that I think can be learned from the experiment is that the students could have said I don't feel like agreeing to participate in the game. And that's it. In such a situation the 20 shekel bill was not worth even a shekel. Total paper.

In short, the money is worth nothing, what is worth something is life, which means the time we live, and if we waste our lives working to earn money, it means we have agreed to the rules the researchers have set. You can disagree. Everyone has a choice. Einstein was not a billionaire and he had a thousand times more power than all the billionaires combined.