Brenda Maddox pulled off her suicide mission admirably. She brings a scientific biography with very little science but a lot of scientists. For those who are attracted to the human side of the great discovery stories, and less to the scientific discoveries themselves, 'The Dark Amplification of DNA' is undoubtedly an enjoyable read.

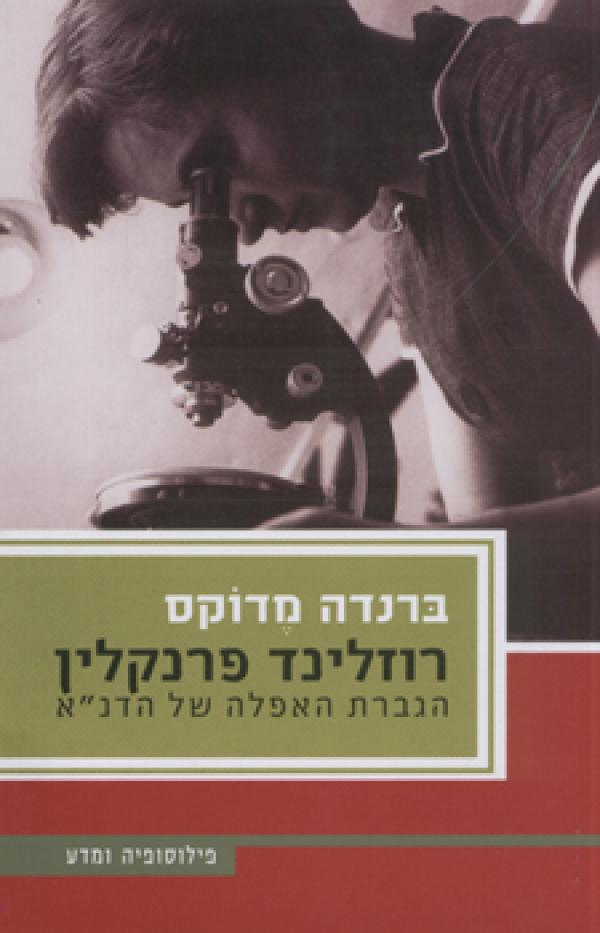

Writing popular science is a difficult and frustrating art. The writer is required to meet all the accepted literary challenges - style, flow, story - and at the same time make sure that the technical explanations are not tedious and break the sequence of the plot. The book that led me to reflect on this elusive art is 'Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA', by Brenda Maddox (Yediot Books 2009, translator: Adi Marcuse-Hess).

On the face of it, Brenda Maddox took on a suicide mission. Maddox - the literary critic of The New York Times and The Washington Post - is an accomplished and award-winning author, but all her previous biographies have dealt with literary figures such as the poets William Yeats and David Lawrence. The only biography of her that comes close to the technical world is that of Elizabeth Taylor, and that's only because Taylor was married to a construction worker (among other things). It takes a lot of courage to approach, from this starting point, a story as complex and charged as the scandal of the discovery of the DNA structure.

Rosalind Franklin was a British physicist who, in the XNUMXs and XNUMXs, studied crystals by projecting and measuring the scattering of X-rays (X-rays). At her peak, Franklin was arguably the world's best expert in this field. The ups and downs of her career led her to study DNA - the molecule that carries the cell's hereditary information - precisely at the historical intersection of knowledge, luck and technology that led Francis Crick and James Watson to decipher the exact structure of the famous linear molecule. The measurements and photographs taken by Rosalind Franklin were an essential milestone on the path leading to the discovery - but her fate was particularly tragic: she died of violent cancer without being recognized by the scientific establishment for her contribution. Crick and Watson won the Nobel Prize for discovering the spiral structure of DNA and since then, more or less, they have had to deal with repeated accusations that they stole the results of Franklin's research and used them without her knowledge and without giving her the proper credit.

Franklin's story has become a classic feminist icon, a prime example of a brilliant scientist who was knocked out just because she was a woman. Franklin is a martyr. Sacrifice on the altar of women's advancement. But in an awe-inspiring display of courage, Brenda Maddox - a woman! - takes a hammer and destroys this feminist icon with her own hands. suicide? Kamikaze.

The style chosen by Maddox indicates that she comes from the world of poets. The book is relatively sparse in descriptions of molecules and crystals, techniques of X-ray scattering measurements and physical explanations. Those who hope to come out of the second half of the book equipped with an introduction to genetics for the first year, are likely to be disappointed. The scientific explanations appear only in those places where the author feels that it is simply impossible to ignore the fact that Franklin worked in a laboratory. What the reader loses in scientific explanations, he gains - in a big way - in a fascinating and amazing perspective on the world in which scientists live and work. This starting point makes 'The Dark Lady of DNA' one of the best science books of recent years.

In the biography of Rosalind, Maddox paints a portrait very far from the feminist ideal. She does not feel sorry for Franklin when she tells us that the 38-year-old physicist never slept with a man, although she was not a lesbian: she was simply a complicated woman, the result of a rigid British upbringing and a mind that was brilliant to the point of bursting. While her friends married and married around her, Franklin toyed with pre-lost youthful crushes on unattainable men. Her most successful relationships were with married couples - where she felt the least threatened, apparently - and only toward the end of her life did she apparently experience true love. Even this one, to the tragedy, did not have time to mature before the cursed disease broke out in her.

Even in describing her relationship with the other scientists around her, and especially the men among them, Maddox does not succumb to the temptation of the feminist cliché. It is true, England of the first half of the twentieth century was chauvinistic - in some academic institutions women are still forbidden to hold senior professorships - but that is not the point. According to Maddox's theory, it seems that the complexity of Franklin's relationships with those around her is a result of her being the daughter of a rich and aristocratic Jewish family. Some of the other scientists considered her, unfairly, a snob. They attributed the harshness and intolerance she sometimes displayed to typical British class arrogance, instead of the fact that she was simply a meticulous and professional scientist who understood that in order to decipher the hidden structure of DNA one had to produce perfect photographs. no less.

When Maddox describes how the race to the discovery of DNA was conducted, she succeeds in conveying to the reader the true complexity of the scientific discovery process. No clichés. No discounts. The scientists in Maddox's book are not larger-than-life geniuses but small, human characters. James Watson and Francis Crick, two mythological figures, are nice and cunning, wise and stupid, honest and foolish - just like the rest of us. Franklin is not preoccupied with incessant musings about her position as a woman in a man's world, but with the daily hassles of obtaining funding for a lab and bickering with her domineering father about political questions. Maddox shows us the world of science exactly as it is.

We, the readers in Israel, are in a particularly interesting bonus book. Franklin was Jewish (Lord Herbert Samuel, representative of the Mandate in Palestine, was a relative of hers) and even visited Israel not long after the establishment of the state. British Jewry is not familiar to most of us: British Jews are not as dominant and influential as those in the United States. Those who have power tend to downplay their Jewish identity. Rosalind Franklin also tended to ignore her origins: she respected all family traditions and obligations, but was not active in almost any 'Jewish' issue (an exception is the important help she and her family provided to the Jewish refugees who flowed into Britain from Nazi Germany). The Jewish point and the question of anti-Semitism - covert and overt - and its effect on Franklin's life, receives very extensive attention.

The answer to the central question in the book - did Francis and Watson steal the glory from Rosalind and leave her aunt behind on the way to the Nobel - is not clear cut. It is clear that without her work they would not have reached where they have, but it is also clear that Franklin herself did not understand the results of her research. She missed the true structure of the DNA molecule - a spiral ladder winding around itself - and even after Watson and Crick published their discovery she still had doubts about it. Maddox's heroes are not made of cardboard: nobody is perfect and knows everything.

Brenda Maddox pulled off her suicide mission admirably. She brings a scientific biography with very little science but a lot of scientists. For those who are attracted to the human side of the great discovery stories, and less to the scientific discoveries themselves, 'The Dark Amplification of DNA' is undoubtedly an enjoyable read.

30 תגובות

Dawn:

I also have no interest in idle debates and therefore I will not cooperate with your attempts to present even this discussion which anyone can see differently than it really happened.

You write - and I quote "Aaron Kellogg is the only one so far who has thoroughly studied Rosalind's workbooks and drafts of her articles."

This is not true - because Lynn Elkin, who co-wrote the Wikipedia entry, also researched (and the fact that she intends to write a book simply does not belong) and so did others (after all, you say that even you researched! If so - you can probably bring serious confirmation to your claims, such as a publication she wrote or even a working paper that was avoided to be published and there is no need for it to be posted on the Klog).

In my opinion, the fact that Franklin never claimed that the discovery was hers also says a lot.

Michael:

I don't want to argue for nothing, but it is appropriate when you respond that you pay close attention to what I write, and treat yourself accordingly. Kellogg did not write a book but 3 articles, the last and most detailed is the one to which I referred you. Note that since it was written in 2004, Maddox could not rely on it at all (even if she wanted to) because it had not yet been written when her book was published. Those who wrote books about Franklin were other than Maddox Ann Sayer (her friend) in 1975. I said Aaron Kellogg was the only one so far. Emphasis on so far. Indeed I know very well that Lynn Elkin is writing another biography about her and has been working on it for several years, but in the meantime she has not yet published except for an article from 2003 in Physics Today. An article which of course also supports what I wrote here. When she publishes her book I will be happy to say that Kellogg and Elkin are the only ones who went through Franklin's workbooks. In any case, the argument on the principle level is completely unnecessary, what I wrote in the first response is accurate, and qualified, and originates from the work done on it by me.

Dawn:

I will not argue with you - both because I have not read Kellogg's book and also because your claims about him being the only one who researched the subject are baseless.

Among the editors of the Wikipedia entry you can find many people who have done this.

I just chose one as an example - Lynn Elkin:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Lynne_elkin

Michael:

I probably wouldn't have written what I wrote if I hadn't known and researched the topic for about a year. And Wikipedia with all due respect is not a reference for anything. And Maddox, with all due respect, is "weak" in the scientific section and focuses on describing the personality and does it very well. I did not "invent" what I wrote, but the one who says this is Aaron Kellogg, the only one so far who thoroughly studied Rosalind's workbooks and drafts of her articles. See Kellogg's article in JMB 2004 issue 335 pp. 3-26

Dawn:

So you say you know better than Wikipedia and better than the author, who must have delved into the story much more than you.

Whatever.

Rosalind Franklin made 3/4 of the way to the discovery and Crick Watson only the last quarter when at least two things were stolen from her - photograph 51 from which they deduced a double coil, and her report to the MRC from which Crick (and only Crick) concluded that the coils go antiparallel. She also contributed to the discovery of the distinctions between A and B, the location of the phosphate and the amounts of water, but they got that from her (somewhat) honestly. She clearly understood at the beginning of 1953, before the news about their model, that it was a double coil and so she also wrote in her work documents, so there is no question at all about it. She was indeed more conservative than them (at this stage of her coolness a little less) and therefore did not want to publish the data. Maurice Wilkins is the only person to win a Nobel for the amazing scientific feat of taking a photograph of her without permission and showing it to Watson

anonymous:

Do you think I exist?

You didn't see me either.

By the way - they definitely saw the DNA (after all, the whole discussion is about "stealing" his photograph).

I have a question, since you talk about DNA and believe it, have any of you readers or writers of the site ever seen DNA with your own eyes, it's so absurd, I've never even seen the atom in my life, how can we believe people who claim this, I recommend you take some hours of life and really check if there is any DNA at all before you talk about it, because there are so many liars it is impossible to know what the truth is anymore

Michael

Science is not mathematics. Scientists present models that they feel are not fully proven or sometimes speculative.

Most of the time the scientist feels that the model is incomplete but he assumes that it has more advantages than disadvantages. for example

Darwin estimated the age of the Earth by hundreds of millions of years (an underestimation) based on fossils

And Lord Calvin, a scientific authority at the time, rejected the estimate since, according to his estimates, the age of the sun is about thirty

million years (today we know that this is a big mistake). Following Calvin Darwin's review, he took it down

In the following editions of his book, the estimate of age is due to Lord Calvin Darwin's criticism.

Discard evolution altogether? Today we know that general relativity and quantum theory do not fit together

Should we therefore reject one of these teachings? Maxwell's laws were not invariant to the transformation

Galileo is why Maxwell avoided publishing them. Reality is more complex than the ability of one formula or one theory to represent it all. The scientist who presents a new theory cannot predict all its consequences and therefore, among other things, he presents it to the criticism of the scientific community.

sympathetic:

I remind you that you are the one who brought up the argument of the courage to be wrong and the whole current discussion is around this point.

If the thought has passed the criticism of the scientist himself - the courage to make a mistake no longer plays a role.

Michael

When I talk about wrong thoughts I'm talking about thoughts that have passed the scrutiny of the scientist himself.

As I mentioned, Einstein also had a number of incorrect models that, following comments on their publication, he published

improved the theory. Science is a human creation based on dialogue between the scientist and the community of scientists

It is the dialogue that allows science to progress.

Regarding the topic of publication, the question is complex. It is difficult to answer the question of what brings scientists

For large discoveries, specific cases can be discussed and that too with a limited guarantee. In my opinion a famous scientist would be

More conservative in the models and theories he puts forward. There is also the effect I mentioned of the fixation of

A late-stage scientist in the cold The longer a scientist has been involved in a certain field the more likely he is

will begin to question the basic assumptions of the field is getting smaller and smaller. The great breakthroughs in science are coming

from changing paradigms.

sympathetic:

It seems to me that you are omitting some important steps in describing the conduct of science.

There is no scientist (except the few who are crooks) who publishes results that seem wrong to him!

This is a stupid act and no one wants to be considered stupid.

Therefore - before a scientist publishes a result and before he submits it to peer review, he submits it to his own review.

Again - if it seems wrong to him - he will not publish it!

I did not say that wrong results and thoughts are not published. People make mistakes here and there. But such results and thoughts are published only when the person who published them thought that they were not wrong.

I still hold my opinion about the harmful effect that you attribute - in my opinion exaggeratedly - to advertising.

In fact it is also hidden by your own words - people receive a Nobel Prize and receive the same publicity many years after they made the breakthrough for which they won the prize.

What prevented them from making good use of the period between the breakthrough and their fame?

Michael

First about the point of wrong thoughts. You write because there is usually no point in expressing wrong thoughts in public. In my humble opinion, this is how science is conducted, by raising false points in the crowd. In the scientific project, questions arise that many scientists try to answer and the feedback they receive from the scientific community improves their models. An example of a wrong model that advanced science is, for example, Bohr's model of the atom, which is a wrong model but formed the basis of quantum theory and there are many more examples. Science is advanced by the scientific community and not by individuals. I will use the analogy of the game of hide-and-seek that you brought up. Many scientists come up with hypotheses and improve them. In the end we only hear about the final and successful model. For example, for the theory of general relativity, Einstein had several failed attempts that were improved by responses from the scientific community until he came up with the exact field equations.

By the way, precisely on the subject of the structure of DNA, it was Linus Pauling (a world-renowned scientist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and Peace) who proposed a completely incorrect model for the structure of DNA. His error is that it spurred Watson and Crick to work quickly because they realized that Pauling was also dealing with the question of structure. So there is some truth in your words that even renowned scientists come up with wrong models, although in my opinion this is an exception.

Regarding the age of the scientists and discoveries, this is not about running competitions or running, the age of the world record holders is greater than twenty. Science is a field where experience is of great importance! In my opinion, the reason relatively older scientists do not reach achievements is the fear of making a mistake combined with fixation on specific fields of research and the academic pressure to publish.

Regarding building models, there is a story about Schwinger who won the Nobel Prize in Physics together with Feynman and Tomanga. Schwinger had a brilliant mind and wonderful analytical abilities, it is said that he was able to calculate the second-order term in perturbation theory in mind. Schwinger abhorred Feynman diagrams, he saw them as an abomination of science. Anyway

In old age, when Schwinger got a little old and his abilities decreased a little (yes, age also has an effect) someone approached him with a question. Schwinger excused himself for a few minutes and was seen drawing a small Feynman diagram on the board.

One more thing about wrong thoughts that precede the right thought:

I once played hide and seek with my niece (who was little at the time - today she is an instructor in the armory).

At one point she told me something along the lines of: "How come you always only find me in the last place you look?"

I explained to her, of course, that it was because I found no point in continuing to look for her after I found her.

sympathetic:

You can find a certain extension in connection with building models inThis response I once wrote in another discussion.

Regarding the chances of a scientist who is not famous to come up with something important and new - there is something in it - but much less than what you say.

A person's intellectual ability begins to fade from the age of 20, so it is quite clear why most scientists reach the peak of their achievements in their twenties and thirties.

Of course, the more theoretical and less experimental the science, the more noticeable this phenomenon.

That Watson and Crick thought of a wrong model before coming up with the right one is not just a characteristic of young scientists.

Even adults allow themselves to think wrong thoughts.

The publication of the person does not limit his thinking but at most his courage to express thoughts in the plural and usually there is no special benefit in expressing wrong thoughts in the plural.

Eddie

I also tend to agree that there was probably no intentional institutional discrimination here, and despite this, as Michael defined it, "...they treated her with a chauvinistic attitude and hid her contribution to the discovery."

In the history of the Nobel Prize there are much more serious cases of injustice and even cases of discrimination (chauvinism):

It was Jocelyn Bell who discovered the pulsars, while the award went to Antony Heuish, her supervisor in the doctoral thesis. Bell had a second record on the article and the Nobel Prize was awarded to Heuish and Riley (by the way, it was the first Nobel Prize awarded to an astrophysicist). I think that chauvinism did play a role here!

Regarding Rosalind Franklin, she claimed that she had the photographs of the DNA molecule, but she did not know how to decipher them correctly.

An opposite case is the discovery of the fission of the uranium nucleus. Otto Hahn performed the experiments but the theoretical explanation

(and the fact that it is fission) came up with Lisa Meitner who was a refugee in Sweden (she fled Germany because she was Jewish). The Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded only to Otto Hahn, even though the basic idea was, as mentioned, Lisa Meitner's.

sympathetic,

Thanks for the insightful comment.

But I again conclude that luck played a decisive role in this entire affair (rather than deprivation on the part of the establishment):

Once - when Duka Watson and Crick did not have enough time to be so institutionalized and senior in a way that prevented them from being, as you call it - 'clowns' (by the way, smart and original and flighty 'clowns', in fact their unusual tendency to play with models they built from iron wires and beads); And a second time - Franklin's untimely death.

Again, there is no doubt that chauvinism played a role in the background, but if it weren't for bad luck, it can be assumed that Franklin's part in the discovery would have been recognized and she would have received a share of the Nobel Prize, as did research partner Wilkins, who, again, was lucky and outlived her.

It also seems that the affair of the theft of the photograph was not what prevented the very recognition of Franklin's achievement, which was of course important even without being the 'discovery' itself.

There is not enough justice in the world, and it is a shame that Franklin did not win.

But in this case there is probably no place to file an 'indictment' for stealing fame. The "investigation file" should be closed due to the lack of cause, and "there should be no recrimination". At the most, a light indictment can be filed, perhaps even a disciplinary one, on another section - reaching a border and stealing a document...

sympathetic:

Indeed, graphic illustrations are one of the tools I present in my lectures on solving puzzles.

In my opinion - the use of physical models can help very rarely - only when the person's imagination is not strong enough to carry them out in his mind without aids.

I, for example, when I come across a puzzle of all kinds of parts that need to be separated from each other, I prefer not to touch it at all and solve it in my head before I apply the solution in reality.

I find it both more convenient and more than waiting (by "waiting" I mean that the solution I found with pure thought will also serve me in solving other problems while the manual solution will usually remain limited to the problem for which the solution was invented).

Eddie

If you are asking in my opinion and it is based on very limited information (Watson's book "The Double Helix") then Rosalind was a very serious scientist, she made sure to check things carefully before jumping to conclusions.

As a single woman in a man's world Rosalind could not afford to make stupid mistakes. The duo Watson and Crick if the officer had a pair of "clowns". They weren't afraid to introduce wrong theories (they had a wrong model for the structure of DNA before the double helix model) and they didn't have a world name to uphold (Crick was a 34-year-old senior

who was still working on his Ph.D.). It was the fact that Watson and Crick were free to speculate and make mistakes that ultimately led them to the discovery. Many times young people without world fame and without fear of making mistakes come to important discoveries, while after fame they do not tend to make more amazing discoveries. Many Nobel Prize winners did not do important scientific work after winning the prize (of course there is the fact that most winners are already very old at the time of winning...).

By the way Michael,

In the context of mathematical and scientific intuitions:

Watson and Crick made their miraculous discovery partly as a result of their tendency to play with models they had built from iron wire and beads. At the time, building models of string molecules was considered an unacceptable and even childish activity... Many times the tendency to play with physical models opens the door to brilliant intuitions and great discoveries. An important intuitive tool in science that was not properly evaluated at the beginning and today is a standard tool are Feynman diagrams.

Eddie:

I never thought that fame was "stolen" from Rosalind Franklin and if you read my comments you will see that they are all reasoning in the opposite direction.

I think, however, that they sinned against her in a chauvinistic attitude and hid her contribution to the discovery.

Ehud and Michael,

I am still satisfied if there was any deprivation here at all - mostly bad luck played here, not chauvinism.

First, Franklin did take the crucial shot, but she obviously didn't get the insight about the double helix. The decisive insight was drawn by others, actual Nobel winners. Its photographic result was an important instrumental condition for the discovery, but it was not the discovery itself. So it is impossible to appropriate the discovery in her favor.

On the other hand, it is possible that she would have won some part of the Nobel, if there had not been a case of bad luck here (Franklin's untimely death 4 years before the recognition of the discovery for the purpose of awarding the prize).

By the way - Wilkins, Franklio's research partner, was among the three Nobel laureates for the discovery. Did he actually take Franklin's place in winning the Nobel - or did he have another unique contribution to the discovery? If he had no unique contribution of his own - it seems possible that he won the Nobel instead, and if she was alive - she would have been the winner.

Whoops.

When I wrote "Moses" in the previous comment, I of course meant Eddie

Eddie

The articles by Watson and Crick and Rosalind Franklin are in the same issue of Nature, the issue was published on the 25

For April 1953. Watson and Karhak's article appears in Ltd. 737 and Rosalind Franklin's in Ltd. 740.

Rosalind's article examines several possible configurations of the DNA molecule and there is no drawing of the double helix as appears in Watson and Crick's diagram.

Regarding the way in which Watson obtained the opportunity to observe the x-rays that Rosalind made, I refer you

The book "The Double Helix" written by Watson is definitely a recommended book. Watson recounts how he was expelled from Rosalind's laboratory in disgrace. Number of quotes: p.m. 150 "I knew more about her results than you imagined", p.m. 151 "My incident with Rosie made Morris blush in front of me to a degree that I had not had before... Morris went into the next room and brought a photograph with the new shape" No need To note that Maurice Wilkins did not argue with Rosalind

(or Rosie as Watson calls her) before letting Watson look at the footage...

Ehud and Moshe:

Here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Double_helix

Write:

The double-helix model of DNA structure was first published in the journal Nature by James D. Watson and Francis Crick in 1953[2], based upon the crucial X-ray diffraction image of DNA (labeled as "Photo 51") from Rosalind Franklin in 1952 [3], followed by her more clarified DNA image with Raymond Gosling[4][5], Maurice Wilkins, Alexander Stokes and Herbert Wilson[6], as well as base-pairing chemical and biochemical information by Erwin Chargaff[ 7][8][9][10][11][12].

sympathetic,

I was not aware that Watson and Crick took the results of Franklin's research 'fraudulently'.

No one disputes that certain observational factual findings were made by Franklin. But it seems from the article that she did not interpret them correctly. If things are like this - it is a philosophical question as to who deserves most of the glory, and it is not clear if there is a deprivation of Franklin here.

According to your words, it turns out that she did understand that there is a double helix here - and if that is the case, everyone will agree that the fact of deprivation is clear. According to this, this is another victim of chauvinism and malice - a phenomenon that we hope is not too common at the higher levels of science.

Eddie

Watson and Crick fraudulently took the results of Rosalind's research. I don't remember the details, but I do

Because Watson somehow got to look at the x-rays that Rosalind took, and only then did Watson and Crick come to the understanding that

The structure of DNA is a double helix. So Rosalind did the important work even if she didn't understand

Completely the same (I think she published an article in the same issue of Nature also with a model of a double coil).

In view of the fact that the work was done by Rosalind and she did not gain fame, there is definitely a deprivation here in my opinion.

"It is clear that without her work they would not have reached where they have, but it is also clear that Franklin herself did not understand the results of her research. She missed the true structure of the DNA molecule - a spiral ladder winding around itself - and even after Watson and Crick published their discovery she still had doubts about it. Maddox's heroes are not made of cardboard: no one is perfect and knows everything."

Therefore it seems that Franklin's case should not be compared to Yonat's case. Yonat understood the results of her research and pursued them consciously, that's why she won her share of the Nobel Prize. Franklin did not understand - before and after Watson and Crick - and therefore the claims of deprivation have no place.

Chauvinism must have been Kane in Franklin's case - but it did not result in deprivation.

Speaking of deprivation, the case of Yuval Naman is much more representative. He published a theory similar to Gal Man's 'Eight Way' - a few months before Gal Man. Gal Man won the Nobel thanks to the mighty American lobby, when there were no lobbyists behind Neman, and he was Israeli after all. Only the French protested, after the fact. Although the Americans later felt uncomfortable - and awarded Naaman with the Einstein Prize (he was the first non-American to win this award) - but his place among the Nobel laureates will remain absent in the future as well... and with all due respect to the other Israeli Nobel laureates, I don't think any of them reach Naaman's stature .

I would like to focus on Watson and Crick in the hope that I will not be accused of chauvinism:

First, Watson and Crick do not have to deal with repeated accusations that they stole the results of Franklin's research and used them without her knowledge and without giving her the proper credit." This is because Francis Crick passed away already in 2004.

One of the most fascinating popular science books written on the topic of discovering the structure of the DNA molecule is "The Double Helix" written by James Watson (of the Watson and Crick duo who won the Nobel Prize). are described in this book

The insiders behind the science highlight the intrigues and more. For example his opening sentence is unforgettable,

Watson begins with the sentence "I never saw Francis Crick in a humble mood". By the way, in the book Rosalind Franklin is presented from a horribly chauvinistic point of view. The book "The Double Helix" was chosen seventh on the list

The non-fiction books of the twentieth century.

It is interesting that Ada Yonat won the Nobel when she used the same basic technique

In order to crack the structure of the ribosome - and in her case too, two male researchers stole it

part of her fame.

zot omeret she ha sefer matim gam le mishe lo mivin klum be genetika?