wonders Ian Wilmot, Dolly's clan and one of the best-known scientists in Britain, who has received permission to start cloning human embryos

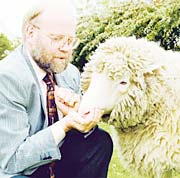

Prof. Wilmot with Dolly the sheep. Very far from the figure of the "crazy professor" who cloned Hitler

Ian Wilmot, who invented and succeeded in cloning the world's first mammal, is now turning his attention to humans. Wilmot moved from his small office at the Roslin Institute near Edinburgh in Scotland to the Royal Medical Research Institute near the Biomedical Center of the University of Edinburgh, after receiving permission to begin cloning human embryos as part of his research into the causes of MND (motor neurone disease).

"When we asked for permission to clone human embryos," says Wilmot, "we didn't think about being the first in Britain or the world." But it is clear that the university's management was thinking about its position in the world ranking of Research Assessment (RAE) when it welcomed one of the country's best-known scientists. In the last ranking in 2001, Edinburgh reached fifth place in the field of life sciences, and now, ahead of the ranking in 2008, the competition is expected to be even tougher, especially in the hot field of stem cell research.

The university believes that a connection between different fields in medicine and biology will be beneficial for research, and that Wilmot will bring his experience, gained over many years of working on sheep and cows. For him, the transition to research in the field of human biology is a continuation of work on animals. At the basic level it is only sex cells and embryos.

At 61, Wilmot is not considering retirement. "I am healthy and productive, and enjoy my work," he says. "It's an advantage. New things excite me like before. Regarding cloning, people are still thinking about the implications and implications of Dolly's experiment. Therefore, the ability to find new angles of view interests me." The fire still burns in his bones, although he sometimes feels the heavy burden of human anxieties such as "Clone Hitler" or questions posed after Dolly's birth, such as "Can we raise the dead?"

Wilmot, who studied agriculture but changed his field of interest and focused on animal research, is a far cry from the crazy professor who cloned Hitler. At the beginning of his career, he studied frozen sperm in a laboratory in Cambridge and tried to find out the reason for the death of embryos. Later he turned to the field of genetic manipulation and began transferring cell nuclei from one cell to another. "It is a mistake to think that we have decided to breed an animal. We worked with embryonic cells with the aim of causing a genetic change," he said.

The Roslin experiments led to the creation in 1996 of two patches cloned from the same embryo, and then, in 1997, to the creation of Dolly, cloned from the udder cell of a six-year-old ewe. The nucleus of the mature cell was replaced by the nucleus of an egg from another female, and was implanted until the end of the pregnancy in the uterus of a third sheep. But surprisingly, and despite the uproar that arose in the world after Dolly's birth, even today no one can explain well how the cloning works. Less than half a dozen articles have been written about what happens in the cell during cloning, said Wilmot, who added that "it is disappointing to see how little has been written and published in the nine years since Dolly was born. We only know a little about what happens during the nuclear exchange."

The medical application of cloning is based on the hope that it will be possible to regrow damaged organs or nerves with the help of cells taken from the patient, so that they are not later rejected by his immune system. "Understanding cloning will allow us to produce special cells for a specific patient without cloning an embryo," said Wilmot, who added that "now, embryos are the fastest way. Those who want to understand the development of a genetic disease will do so faster if they follow the transmission of the nucleus."

Wilmot is supposed to research motor neuron cell disease - which is considered fatal and kills within about four years. According to him, his team will work together with Korean scientists who have become famous for the sensational progress in the field of human cloning. Cell nuclei from MND patients will be transferred to eggs donated by women who have undergone fertility treatments.

In response to the opponents of the study, who claim that it was done irresponsibly, Wilmot wonders "why not combine the studies on animals and humans". According to him, long years of animal research have produced little understanding of the disease, and people continue to suffer and die from it. "We are not doing enough to understand the disease," he said. In his opinion, discoveries can be used for good or bad. "The role of the scientist is to explain what the possibilities are, and to help people understand the issue."

As progress in medicine has led to discussions about the end of life, such as the question of when to disconnect the resuscitation devices, a discussion should be started regarding when life begins, according to him. The Catholic approach according to which life begins at the moment of conception stems from the recently published Vatican statements. Earlier, the prevailing view was that life begins when the fetus begins to move in the womb. According to Wilmot's ethics, life involves recognition and awareness. Because of this, the fetus becomes a person only after its brain has developed, many weeks after the stage of development of the embryos Wilmot intends to use.

https://www.hayadan.org.il/BuildaGate4/general2/data_card.php?Cat=~~~232286079~~~111&SiteName=hayadan