Bringing mammoths and other extinct creatures back to life is actually a good idea

Some strongly argue that bringing extinct species, such as the woolly mammoth, back to life using remnants of genetic material left in their bodies is a bad idea. But it seems that rejecting the idea is too hasty. There is truth in this idea and it certainly deserves discussion, with an open mind and a multidisciplinary perspective.

The purpose of scientific research dealing with the resurrection of ancient species is not to recreate perfect copies of these extinct creatures, nor to create such a creature in a one-time fashion for laboratory experiments or as a scientific stunt for display in a zoo. Bringing extinct creatures back to life is designed to leverage the best of ancient DNA and synthetic DNA to help the evolutionary adaptation of existing ecosystems to the extreme environmental changes in the modern world, such as global warming, and possibly even reverse the trend.

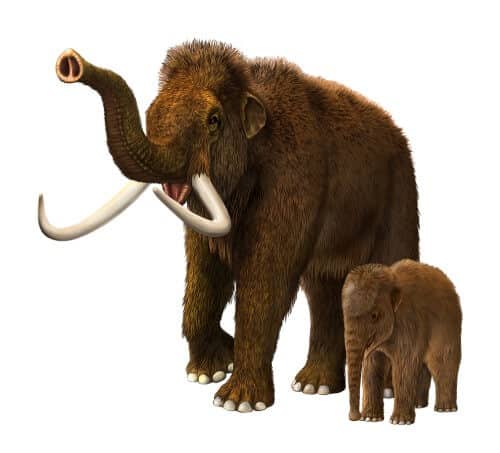

There are ecosystems that depend on several important biological species called "keystone species". Many such systems have lost the diversity of species that characterized them in the past, since certain species no longer adapted to their environment. In a world where environmental changes are occurring, the need for ancient biodiversity may re-emerge. For example, 4,000 years ago, the tundras of Russia and Canada were characterized by a much richer ecosystem based on grass and ice. Today they are in the process of thawing, and if the process continues, they may emit more greenhouse gases than all the forests on earth if they were all burned to the ground. A few dozen changes in the genome of the modern-day elephant, which would give it subcutaneous fat, woolly hair and mammary glands, may be enough to create a species functionally similar to the mammoth. The restoration of this key species to the tundra may delay or even prevent some of the effects of warming.

Mammoths can maintain lower temperatures in these areas in several ways: (a) by licking the dead grass, which will allow sunlight to reach the spring grass whose deep roots prevent soil erosion; (b) increasing the reflected light by felling trees, which absorb sunlight; and, (c) punching holes in the insulated snow layer so that frozen air penetrates the ground. And in the arctic regions, mammoths will likely be much more protected from poachers than elephants in Africa.

The idea of turning back the extinction clock is not a new idea. Medical research scientists have succeeded in reconstructing the complete genetic sequence of the endogenous retrovirus HERV-K as well as that of the virulent virus strain that caused the deadly 1918 flu pandemic. New insights into these resurrected species could save millions of lives. Several other extinct genes, including the mammoth's hemoglobin gene, have also been reconstructed and tested for new properties. It may be that there is no real need to go from reconstructing single genes to reconstructing most of the genes of a chicken or an extinct mammal, the number of which reaches about 20,000. And even if it turns out that there is a need for it, it doesn't seem like it will be difficult to do. The costs of various technologies required to implement the process are not high and are steadily decreasing.

When it comes to breeding and raising animals on a large enough scale to be able to release them into the wild, the task is much more ambitious, although, as far as the costs are concerned, they are not particularly high compared to the costs involved in raising farm animals or preserving other species of wild animals in danger of extinction. We can even reduce these costs if we use genetic means to improve the species we seek to resurrect, by improving their immunity and fertility and their ability to extract sufficient nutritional values from the available food and successfully deal with environmental stress.

Along with bringing extinct species back to life, the process may help existing species by restoring their lost genetic diversity. The genetic inbreeding among the population of animals called "Tasmanian devils" (Sarcophilus harrisii) has reached such extensive dimensions [due to remnant reproduction] that most members of this species can transfer cancer cells to each other without developing antibodies to the disease. A rare type of contagious cancer that has spread in the Tasmanian devil population through mutual face bites is putting the entire species at risk of extinction. Restoring ancient genes of these animals, with genetic diversity and tissue compatibility, which regulate the mechanism of tissue rejection, may save the species from extinction. Similar arguments are also valid for amphibians, cheetahs, corals and other groups of animals. Ancient genes may make them more tolerant to various chemicals, heat, pollution and drought.

However, resuscitation is not a panacea and is not necessarily applicable to every ecosystem at risk. Preventing the continued extinction of elephants, rhinoceroses and other endangered species is of crucial importance. There is no doubt that we must set priorities regarding the allocation of the limited resources available to us for the conservation of species. But it would be a mistake to treat the issue as a zero sum game. Just as putting together a new vaccine can free up medical resources that, in its absence, would be diverted to the treatment of patients, so the resuscitation may help environmental conservation activists, as it gives them new and powerful tools. Even if it is only a possibility, the potential inherent in it provides sufficient reason to continue to thoroughly investigate the issue.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

About the author

George Church (Church) is a professor of genetics at Harvard University Medical School and heads the university's Center for Excellence in Genomic Sciences, which operates under the auspices of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The article was published with the permission of Scientific American Israel

9 תגובות

A cold economic analysis will show us that the surest way to bring mammoths into the world will come through startups financed by very rich angels with the goal of selling the products to zoos around the world. When such a startup cracks the matter and grows mammoths - zoos around the world will be ready to pay tens of millions of dollars for each mammoth because tens of millions of tourists would come every year from around the world to witness the wonder.

By the way, at least from what I read, according to the scientific consensus in 20

The next thousand years an ice age will come, but global warming is a matter of the next few decades so it is probably more critical

My father, is this all because of greenhouse gases, headed by carbon dioxide? It's not that I don't believe there is global warming and it's not that I don't believe it's because of human activity, I also believe that people like you are the solution and you may have already solved it. Twenty years ago, except for Germany, no one in the world would have thought about solar energy because it was simply too expensive and today it already seems close to being economically feasible. Fossil fuels are becoming more expensive and have already reached an efficiency of over 40 percent in solar energy, and on the other hand, carbon in its fixed form will probably take a more and more significant place in the life of the human race so that before long the human race will be a carbon fixer, this is the assessment of a layman like me, continue your fight against emissions Just please not in our country that already has to finance allowances for exploitative sectors, huge salaries for associates and crazy security costs. We are perhaps the only place on the planet that has managed to defeat the phenomenon of desertification and thereby fix generous amounts of carbon, let's be satisfied with that

Gilgamesh, the ice age was delayed by at least half a million years because of some small animal less than 2 meters tall.

Yes ! Yes! Yes ! Resurrect the mammoths and if possible all the cool animals. Damn! If I were a woman I would volunteer to conceive a Neanderthal. Unfortunately, letting such a project go public will bury it, if you need some adventurous millionaire who wants to build a park in the style of Jurassic Park, then there will be no way back and the tree huggers of all kinds may agree to release them into the wild. Regarding global warming, what is your point? Aren't carbon supposed to be the building blocks of the future? Computers, cars, airplanes, buildings will be built from carbon fiber, humanity will abandon fossil fuels in favor of thermonuclear and solar energy, and don't forget that an ice age is waiting for us when we will surely thank God for every carbon dioxide molecule in the atmosphere

In short, the day is not far off when Tut Anach Amon will smile at us and loudly announce: I told you that I will live eternal life.

The description of the possibility of a recession or even stopping the warming by bringing back the mammoths

(or a derivative of them) to the arctic environment is a bit delusional and even exaggerated,

It is appropriate and correct to deal with species that have been extinct in recent centuries and to preserve the existing ones,

It is appropriate and right to find ways to slow down or stop global warming,

It's a shame to waste resources on trying to combine the two issues,

a combination destined for failure,

Too bad for the effort…

All the animals were brought from space…

All you need to do is order them again...

It doesn't seem to me that bringing back a few poles to the wild in the Siberian steppes will change global warming. It is more true that we have an obligation to return to nature or to the zoos some of the species that we helped to destroy.