Perhaps the secret to brain control of prosthetic limbs is to ignore the brain altogether

In recent years, scientists have presented many achievements in wiring prosthetic limbs directly to the brain. Some studies have reported that severely disabled people, or monkeys used as surrogate subjects, used bionic limbs and controlled them with the power of thought to lift a mug or "give fun", for example.

Many of these devices have a long way to go to be more than smart lab displays, requiring precise and continuous tuning to maintain an effective connection to the brain. Reliable reading of signals from electrodes implanted in the brain is one of the great challenges of neuroscience and biomedical engineering, and it will occupy future generations of researchers as well.

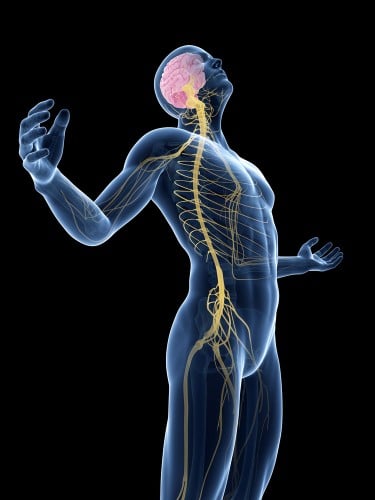

Meanwhile, the scientists and engineers found a way to bridge the missing link. Instead of trying to decipher the flurry of signals inside the brain, some researchers are creating prostheses that receive commands from the nerve endings left after the amputation.

The best example so far is probably the robotic calf developed at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. The scientists there attached a cylindrical mesh of 32 electrodes to the thigh of Zach Wotter, now 96, after his tibia was severed in a 2009 motorcycle accident. In September 2013, the doctors reported in the New England Journal of Medicine that these electrodes pick up signals coming from Zach's brain at the peripheral nerve endings, and instruct the prosthetic leg to walk and even climb stairs.

In order to overcome the engineering challenge of extracting clear and strong signals from the remaining nerves in Vauter's leg, the doctors connected the nerves responsible for foot movements to muscle remnants, which act as natural signal amplifiers. "Muscle amplifies motor commands about 1,000 times," says Todd Kuiken, director of the institute's Center for Bionic Medicine.

Another new prosthesis used a similar peripheral link to transmit tactile sensation signals in the opposite direction: from the limbs to the brain. Researchers at Case Western Reserve University implanted tiny electrodes in the upper arm of an amputee and connected them to a robotic arm and hand. When the sensors in the bionic hand detected pressure, the electrodes stimulated nerve endings to transmit the information about the touch to the brain. The researchers tested the device by asking a blindfolded patient to pick a grape. "He was able to grip it with enough force to pick it, but not enough force to crush the fruit," says Dustin Tyler, a professor of biomedical engineering at Case Western.

Direct links between the prostheses and the brain will still be required in the future in patients whose spinal cord injury prevents the transmission of nerve signals to the limbs. Meanwhile, connecting to peripheral nerve endings may help some of the million amputees in the US walk more easily.

The article was published with the permission of Scientific American Israel

One response

א