Captain Alejandro Malaspina mapped the western coasts of South America and North America at the end of the 18th century. He was then thrown into prison

John Noble Wilford New York Times

There is no need to introduce Captain James Cook, a Yorkshireman who climbed the ranks and commanded three sea voyages, which opened the expanses of the Pacific Ocean to the Europeans and were the culmination of voyages of discovery in the 18th century. His horrific death in 1779 only intensified the aura of the hero attached to him.

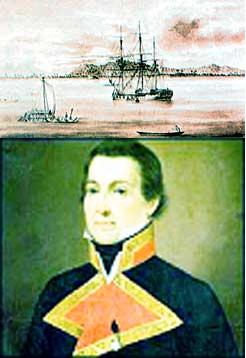

Alejandro Malaspina was the Spanish answer to Captain Cook. Malaspina led a five-year research expedition, from 1789 to 1794, in which he mapped the western coasts of North and South America, sailed in the Pacific Ocean as far as the Philippines and reached China. But Malaspina's achievements have been poorly documented. Upon his return to Spain, he ran aground on domestic politics and was thrown into prison. His diaries were shelved, and his name was almost completely erased from Spanish history.

Malaspina was recently rescued from oblivion. A complete version of his diaries was published in 1990 by

The Maritime Museum of Madrid, and the English translation, "Voyages from Laspina 1794-1789", will be published by the "Cloit Society", an organization that publishes reports on geographical discoveries based in London. The second volume of the diaries, to be published later this year, was presented at a symposium held in April at the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University in Providence, Long Island.

Malaspina was 33 years old when he set sail from Cadiz on July 30, 1789 as commander of the largest Spanish scientific expedition ever. He was Italian by birth, like Columbus and Amerigo Vespacci before him. As the third son of a low-ranking nobleman, he was forced to look for another place to live and became an officer in the Spanish navy.

Malaspina's expedition was asked to tour the Spanish territories in America and the Philippines, prepare new nautical charts and gather information about the natives, flora and fauna, and other natural resources. The team included cartographers, botanists, zoologists, artists and officers who would act as ethnographers.

The expedition drew inspiration from the voyages of Captain Cook and relied on his discoveries and to a lesser extent on the voyage of the Frenchman Jean-Louis Bougainville. In his diaries, Malaspina often quoted Cook's advice. For the purpose of the journey, two three-masted ships, 36 meters long, were built. Their flat shape allowed them to enter shallow water harbors and river estuaries.

The "Descubierta", commanded by Malaspina, and the "Atravida", under the command of Jose Bustamante, arrived in South America, rounded Cape Horn and toured for about three years along the western coasts of South America and North America, from Chile to Alaska. At each mooring point teams of cartographers determined the position based on the sun and the stars and checked the chronometer to determine longitudes. The botanists and zoologists went deep inland and collected samples.

Malaspina wrote in his diary that "many times the crew members had to return to the sea to recover from the exhausting effects of being on land, instead of recuperating in port from the difficult sea life". It is not clear if the crew members suffered mainly from the too hard work on the beach, or were exhausted due to the revelry they had.

North of Mexico the sea and beaches became less familiar. Strong winds drove the ships away from the coast just as the expedition members were supposed to discover the source of the Columbia River. In those days, the expedition investigated reports, according to which a sea passage connects the Pacific Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean.

After the search was stopped, the team began examining the cultures in the Pacific Northwest. Scientists believe that the ethnographic research in the region was one of the main achievements of the journey. The Spanish motives were not purely scientific. Cook spread hints about treasures and natural resources in Alaska, and the Russians began to penetrate the area.

Malaspina conducted research in the Tonga Islands, a place Cook had never visited. The Spanish captain also found time to model for one of his painters, alongside two young island girls.

Although in his diaries Malaspina reported mainly on daily life in the middle of the sea, on the weather, on distances, diseases and dwindling food reserves, experts claim that the character of the writer emerges from between the lines. He was not a tough commander. His views on the people he met were humane to an unusual degree.

Andrew David, a retired British hydrographer who compiled the translated logs, said Malaspina developed symptoms of depression in the last months of the voyage. He sharply criticized some of the officers, although there were no noteworthy cases of disobedience or mutiny attempts.

An ominous feeling may have come over him. After his visits to the Spanish colonies, Malaspina criticized them, both politically and economically. The empire began to sink, and not long after became prey to the liberation movements. Malaspina did not hide his liberal views regarding the reform of the colonies. While the expedition was in the Pacific, King Carlos III died, a visionary ruler who believed in the ideas of the Enlightenment. His place was taken by his son, Carlos IV. The French Revolution raised concerns in all kingdoms, especially in Spain. The new king and his reactionary prime minister saw Malaspina as a dangerous radical.

Malaspina was tried in secret. His rank was stripped and he was sent to prison and from there exile, until the day of his death. The travel records, which include 300 diaries, 450 notebooks and 183 maps, were confiscated and stored, or disappeared, without being published or studied. Everything was doomed to oblivion, including the commander of the expedition.

Malaspina died in 1810 in northern Italy, not far from his birthplace. The songs of praise that history has showered on James Cook have passed over him.