The Alhambra Edict signed by Ferdinand of Aragon and his wife, Queen Isabella of Castile on March 31, 1492 and prohibiting by law the Jewish settlement in Castile and Aragon, changed the face of Jewish history beyond recognition

The Alhambra Edict, signed by Ferdinand of Aragon and his wife, Queen Isabella of Castile on March 31, 1492 and prohibiting by law the meeting of Jews in Castile and Aragon, changed the face of Jewish history beyond recognition. Prof. Shmuel Raphael, dean The Faculty of Jewish Sciences At Bar-Ilan University, the founder of the Salty Institute for Ladino Studies and recipient of a decoration by King Felipe VI of Spain for a special contribution to the Spanish nation, writes about the deportation from Spain and the glorious Jewish culture that was born in its wake.

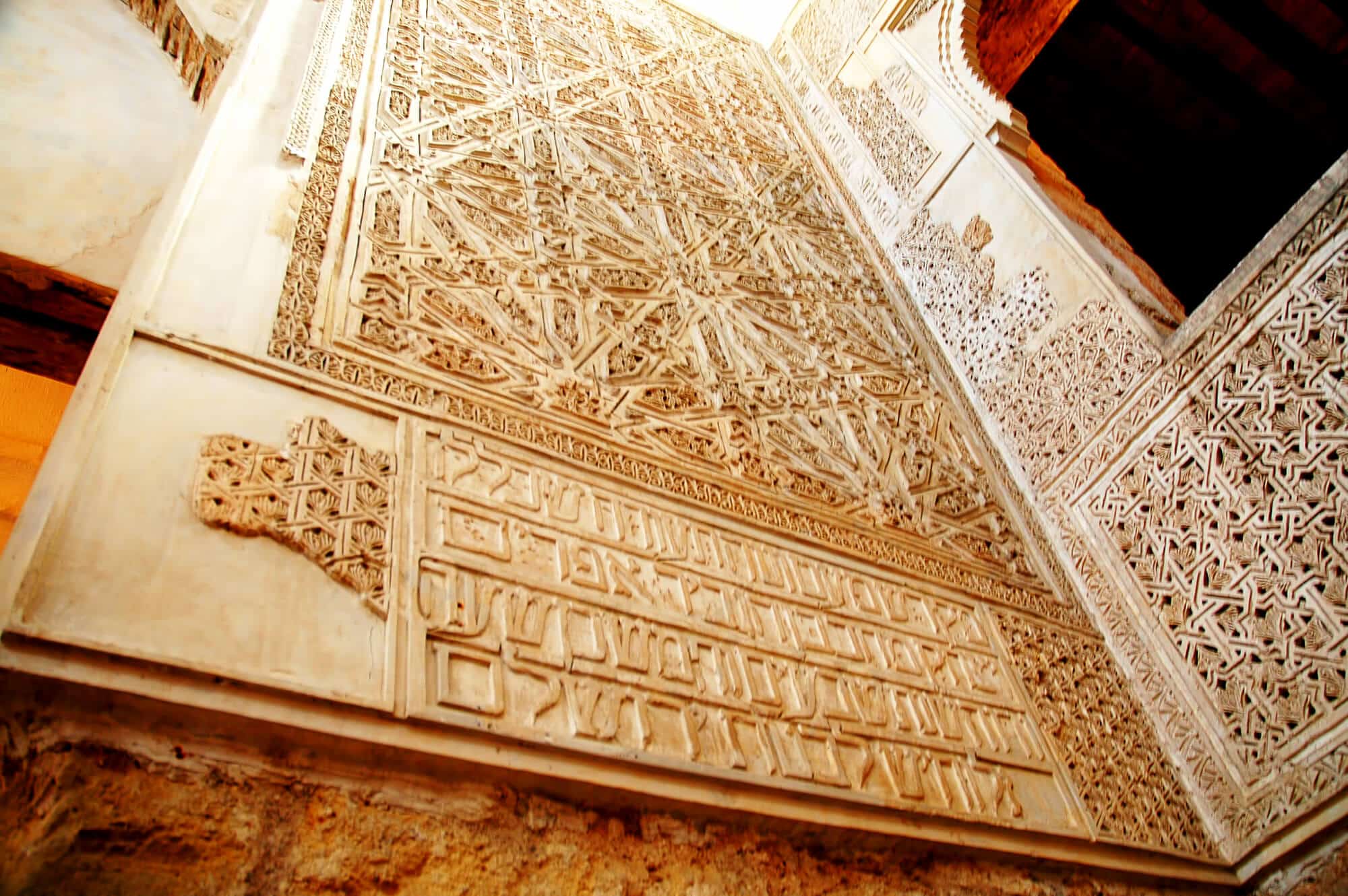

After about 1,500 years, during which a vibrant and multi-faceted Jewish community operated in Spain, it came to an end with the publication of the decree of expulsion, which was signed by the Catholic kings Fernando and Isabel. The two married in 1469, and thus united, in practice, the forces of a divided kingdom in favor of the establishment of what they saw before their eyes as the Spanish kingdom. The deportation order was also the culmination of a long and protracted process, during which the living conditions of the Jews in Spain became more and more complex, including the establishment of the Inquisition. After the scroll was closed on the Islamic rule in Spain and after the Catholic kings settled in Granada in January 1492, they ordered - as a first step - to evacuate all the Jews from Granada. Two months later, on March 31, 1492, they published the deportation order ordering the deportation of all Jews from all regions of Spain, thus ending Judaism in Spain.

It is difficult to impossible to describe the wanderings of 250 thousand deportees from Spain across countries and seas. The direction of the migration was unclear. Various arrowheads branched off from Spain, and the central one made its way to the eastern Mediterranean basin. Throughout the journey, most of it on foot, the social, family, professional and economic structures of the group of deportees were increasingly undermined. This group, who wandered without knowing where they were headed, kept the Spanish language, which gradually became the Spanish-Jewish language, which today is known as Ladino. This language served as a cultural bridge, on which not only the Spanish culture was preserved, but the Jewish-Spanish culture was redeveloped and rose. Ladino was a tool for cultural accessibility and a reunion between the contents of the Jewish world and the language of those deported from Spain. The first deportees settled in the Jewish Balkans a generation or two later, yet despite the tortuous ways they went through, they managed to establish magnificent Jewish-Spanish communities that became a model for imitation throughout the Jewish world. Thessaloniki, Istanbul, Izmir and the like became the cities of the Spanish-Jewish culture that grew after the expulsion from Spain. The deportation event, which began as a terrible trauma, ended a few centuries later as an unprecedented cultural flourishing. But this flourishing also ended this summer, when Ladino speakers were deported to extermination camps on European soil during the Second World War.

More of the topic in Hayadan: