An American farmer who illegally cloned a giant sheep - and tried to develop a new hybrid species throughout the United States and release it into the wild

Dolly - the first cloned sheep. Source: Wikipedia, Tony Barros

The genre of horror fiction is replete with clichés about the "mad scientist", harnessing the most advanced scientific tools to violate the laws of creation, nature and common sense. The most memorable of all is probably Doctor Frankenstein, who created his own private monster. And of course, he had to deal with his twisted palm creation when it got out of his control and demanded the doctor to revive a mate for him as well. But this is just an imaginary horror story, of course.

Now you can also find a version in reality: an American farmer created, against the law, a clone of a giant sheep - and tried to develop a new hybrid species throughout the United States and release it into the wild. You read that right: he didn't try, but already succeeded. And along the way, he may have provided an answer to a question that scientists have begun to ask in recent years: where can we find the cloned humans that were promised to us two decades ago?

But let's start at the beginning: the art of cloning.

The art of cloning

Ian Wilmot was an embryologist - a scientist who studies embryos - anonymous until the mid-nineties. He tried for many years to breed animals. Simply put, he wanted to duplicate them: to make many exact copies of one particularly successful animal.

After many long attempts, Wilmot found the magic formula in 1996, and carried out the world's first successful human-made cloning. The first product of his research was the first cloned sheep, named Dolly.

In Wilmot's historical study, the researcher took an egg from one sheep and removed the nucleus from it - the region containing the embryo's genetic code. He left the egg hollow and empty, then inserted into it a nucleus that came from one of the cells of a different breed of sheep. The initial procedure was clumsy and clumsy, with more than 250 failed attempts, but one was successful. The egg that was fertilized with the foreign nucleus began to divide, turned into a tiny embryo that was implanted in the womb of a sheep, and in the end - emerged into the world as the first cloned sheep, named Dolly.

Dolly was an exact copy of the original sheep from which the nucleus was taken. The implications were enormous: throughout history, farmers worked hard to improve their farm animals. Every farm had a cow that provided more milk than the others, or a sheep with better quality wool, or a sturdier horse. Farmers wanted to promote these traits, so they would cross the most successful animals with others to get offspring with the desired traits. But genetics is a fickle art, and only half of the genes of the favored animal would pass on.

Cloning technology allows us to circumvent this difficulty. There is no need to mix the fine genes of the chosen animal with those of a son or partner. Instead, we simply copy the original animal in its entirety, for all its genes. The most successful sheep will reproduce thousands of times and continue to be the most successful.

And if it can be done in farm animals, why not in humans?

Human cloning

In the book "Nexus" by the futurist and science fiction writer Ramez Naam, an elite unit of extraordinary soldiers is described: all of them are exact duplicates of each other. That is, clones. The Chinese government found the perfect soldier, then used cloning technology to clone him to infinity. The same idea can also be found in the films "Star Wars", where one of the most successful mercenaries in the galaxy is cloned, and based on his genetic code, a huge number of new soldiers are produced in his image.

Incentive to clone humans, therefore, is abundant. Belligerent countries may want to raise a new generation of soldiers, for example. Or - what is more likely - a new generation of geniuses. All they have to do is obtain a cell sample of the strongest or smartest humans today, start a national cloning and embryo implantation operation in the wombs of patriotic mothers and enjoy the products in two decades.

But it turns out, as usual, that the road to the future is full of obstacles.

Scientists and companies that tried to use Wilmot's cloning technology on cells from great apes - which includes humans - found that they were not ready to undergo the procedure successfully. Some of those scientists tried to claim that they had succeeded in cloning humans, but they did not agree provide evidence of this, Or whose studies have been completely refuted.

Eleven more long years of research were required until, in 2007, a group of American researchers finally managed to find the right conditions for cloning monkeys. Even then, the cloned embryos failed to develop A real monkey cub. Another eleven years had to pass before Chinese researchers announced the birth of The first cloned monkey.

And what about humans? To the best of our knowledge, no one has yet succeeded in developing a human clone that would also be implanted in a woman's womb. In 2014, there was success in cloning human embryos in early stages of development, but these were not allowed to develop beyond that. However, given the current state of successful monkey research, and the success in creating human embryos, it would certainly not be a big surprise if a cloned, healthy human baby is born in the next few years.

But will we even know about it?

Uncle Schubart had a farm

Henry T. Greeley, professor of law and genetics at Stanford, raised a particularly intriguing question in a 2020 article: Where are those clones?

Greeley claimed that cloning technologies were on the verge of success in humans, and recognized the great benefits that governments and individuals could derive from them. Why, then, do we not hear about researchers trying to clone humans?

Maybe - just maybe - the answer is that we don't hear about them because they don't want to. Just as Arthur Jack Schubart did not want the authorities in the United States to find out about the private cloning project he started on his farm.

If you come to visit Montana in the United States, you can drop by the "Alternative Sheep" farm, also known as Schubart's farm. There, in an area of almost one million square meters, Schubart is engaged in the purchase, herding and sale of "alternative sheep", such as goats and mountain sheep and other types of livestock. He sells these animals mainly to game reserve operators, who want to attract the most curious hunters.

So far, everything is kosher. A bit smelly, but kosher. It is allowed in the United States to hunt certain animals, in certain areas, at certain times of the year. But Schubart had to be ambitious - and decided that ordinary American mountain goats weren't good enough for him.

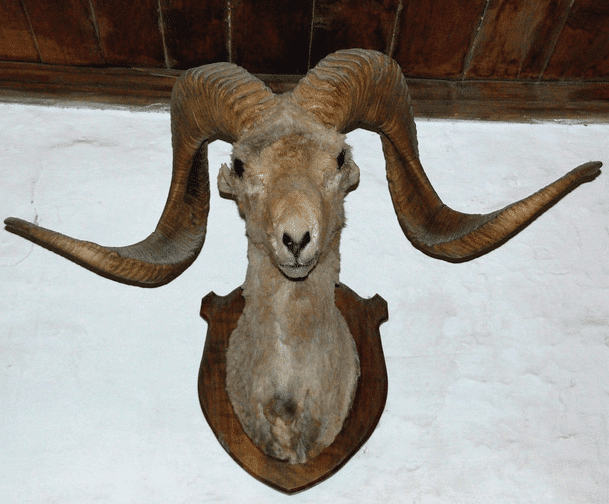

Schubart surveyed the variety of ungulates in the world, and decided that the sheep known as the "Argali Marco Polo sheep" was the perfect sheep for hunting purposes. One can understand his affection for that sheep. It is the largest in the world, and the males can reach a weight of more than 150 kilograms, with large and impressive horns almost two meters long from side to side. What else? The Marco Polo sheep lives in the highest mountains in Central Asia, and is in danger of extinction. Any attempt to sneak the sheep into the United States was doomed to failure.

This is where modern science comes into play. Schubart realized he didn't have to smuggle a whole live Marco Polo sheep into Montana. If he could only obtain the genetic material of a Marco Polo sheep, then he could simply clone one for himself within the borders of the United States.

The amateur embryologist ordered select parts from a deep-frozen Marco Polo lamb, and in 2013 transferred the genetic material to a private laboratory, which produced cloned embryos of that lamb. The cost of cloning? Only $4,200, according to Court records. He implanted the embryos into sheep on his farm, and a few months later he was awarded the litter of a cloned Marco Polo sheep - probably the first of its kind in the United States. He called him "Montana Mountain King". We will call him "King" for short, from now on.

Schubart realized that there was little point in selling King as a game animal. Even the most avid hunter would not be willing to cover the cost of cloning a single Marco Polo sheep. Therefore, he decided to give King the best life a male sheep could enjoy. He sent King on a breeding expedition, in order to create new hybrid strains that he could sell for good money. King did his job with remarkable dedication, but when he was unable to perform at the required capacity, Schubart milked him himself rations of semen and sold them to other sheep breeders across the United States.

"It was an ambitious plot to create massive hybrid sheep species." He explained Assistant Attorney General Todd Kim, of the Environment and Natural Resources Unit of the United States Department of Justice, in a news release released to the public in mid-March 2024. "Schubart violated international law ... designed to protect the viability and health of native animal populations."

Lessons learned

What do we learn from this whole affair?

First, that once a certain technology becomes efficient enough, any private laboratory can easily use it. A clone that would have cost hundreds of thousands of dollars twenty years ago costs only $4,200 today.

Second, cloning technology requires much less human labor today. This means that the fewer people involved in the research, the lower the risk that the research will be published. This is probably why Shubart was able to hide his actions from the authorities for almost an entire decade.

Thirdly, and perhaps this is the most obvious insight: people will do stupid things for the sake of money, or for the sake of ideology. They will break the law and endanger the environment, if they think that in this way they can increase their profits. There is a reason for the existence of the laws that are supposed to protect the environment from invasive species and blatant interference with nature. There is a reasonable chance that at least some of Schubart's hybrid sheep have already been released into the wild and started mating with the original sheep in Montana and other states in the United States. What will be the effect on the sheep population? we do not know. But somehow, I don't think that bothers Schubart too much.

All three of these insights together should raise a big question: Is it possible that similar experiments also took place in humans under the radar? Is there a chance that the first cloned babies have already been born, and we are simply not aware of their existence?

Maybe. But probably not. The limiting factor at the moment in any cloning attempt is the success rate. Schubart was able to bring King into the world only thanks to the fact that he also owned his own farm, and implanted the embryos in 165 sheep he owned - and had one healthy litter. In monkeys, the best success rate in recent years has been A little less than ten percentThe meaning is that any experiment in large-scale human cloning would have required the participation of dozens - perhaps hundreds - of women who would grow the embryos in their wombs. And the vast majority would abort the fetuses, with all the medical complications associated with that. It is very hard to believe that today, in the age of social media, such an experiment would have managed to remain hidden from the public eye. And now that I've said that, I have to admit that there have been conspiracies ever since. Many governments have an extensive history of hiding information from the public. In China especially, the government controls the Internet with a high hand, and manages Camps where more than a million Uyghurs are imprisoned. According to reliable sources, there is also an extensive culture of organ harvesting from prisoners Is it really so exaggerated to think that China might run another small and exclusive camp, in which one particular organ will be used: the uterus?

It's a chilling thought, but there's no reason to rule out the possibility.

To her and a thorn in her

One of the most important forces in technology and science today is the democratization of research and development processes. The power of development goes to the masses, and they produce a great abundance of new inventions. Most of them are bad - like any new idea - but the successful ones change the world.

But what happens when one bad idea can cause damage to the environment that will take generations to repair? This may well be the result of Schubart's clones. And what about other clones that are conducted under the radar? Humans, apparently, have not yet been cloned in this way. But it's hard to believe that out of all the millions of farmers in the world - breeders of fish, sheep, cattle and more - none of them has yet tried to illegally clone animals themselves, or leap directly to even more advanced genetic engineering techniques.

Should we stop the progress of technology in the field? Limit her only for a while? I hope not, as the result will be a slowing down of the pace of technological progress. But governments should continue to monitor what is happening on their territory to reduce the chance of a successful experiment in cloning or genetic engineering, which will change the world even before we have time to understand what happened there. The fact that it took ten long years for Schubart's experiments to be discovered suggests that this will not be an easy job for the government.

Good luck to all of us, in the future of giant woolly sheep.

More of the topic in Hayadan: