The institute's scientists discovered a new type of inflammasome - a "smoke detector" of the immune system that ensures more precise control of the height of the flames of an inflammatory reaction. The findings may pave the way for treatments for inflammatory bowel diseases

Many crowns have been linked to the Abraham Accords, but so far it has not been revealed that the normalization arrangements between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and other Arab countries have unexpectedly advanced as well Research in the field of immunology. An act that was like this was: following the agreements, Prof. was invited Eran Alinev From the Weizmann Institute of Science to a scientific conference in Dubai. On his way to lecture at a conference, he shared a taxi with a German immunologist. "Prof. Aika Letz told me on the drive about an unusual protein cluster that he was researching, and I told him that my lab was researching the exact same cluster," Prof. Alinev recalled. "We started exchanging ideas and that's how we helped each other complete the missing pieces of the puzzle."

The cluster that worked its magic on the two laboratories is a new type of "inflammasome" - one of those flower-like clusters of proteins that serve as the "smoke detector" of the immune system. Unlike the smoke detector fixed to the kitchen ceiling, inflammasomes reassemble themselves each time in the face of danger, and then execute a controlled inflammatory response: massive production of cytokines - inflammatory chemicals that lead to the death of cells that have been contaminated or damaged, thus preventing the possibility of more extensive damage in tissues. When the detectors do not work properly, the controlled inflammatory response does not take place, and the result may be uncontrolled inflammation that leads to extensive tissue damage and disease outbreak.

To ensure a quick and accurate immune system response, each type of inflammasome specializes in sensing a certain type of threat. For example, there is an inflammasome that knows how to sense DNA molecules that are out of place - that is, they float in the cell fluid instead of being preserved and formed in the nucleus - evidence of a bacterial, viral or fungal infection or simply the distress of the cell.

"Our discoveries sharpen the understanding that mucosal cells, such as the lining of the intestine or the skin envelope, are actually cells of the immune system, and they constitute the first line of defense against dangers and invaders from the outside"

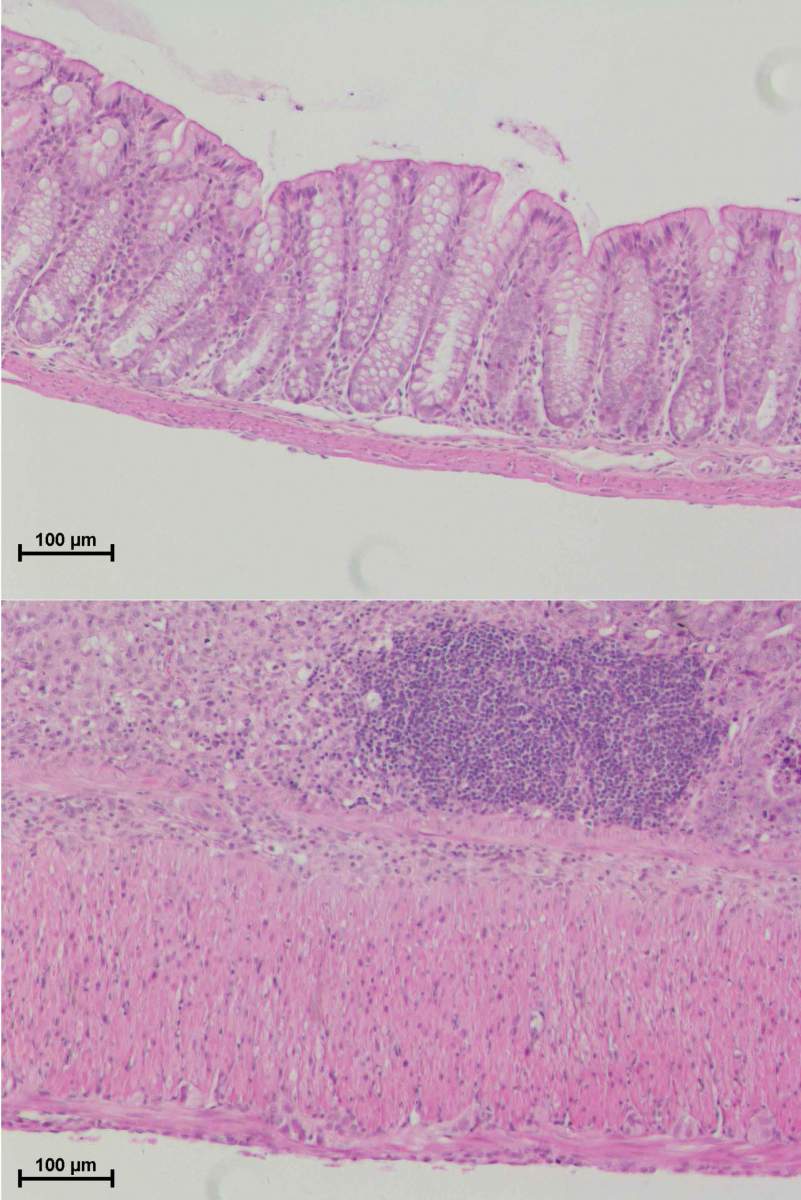

An in-depth knowledge of inflammasomes and their various types can pave the way for treatments for a variety of inflammatory diseases. For this very reason, Prof. Alinev's group set out on a search for a challenging target: a new type of inflammasome. For Prof. Alinev this was not a new adventure: being a young researcher, during his post-doctorate, he discovered a new and first-of-its-kind inflammasome called NLRP6. The uniqueness of this inflammasome is that, unlike all the five inflammasomes that were known until then, it is not formed in the cells of the immune system, but in the cells of the intestinal lining.

In their search for the new unknown inflammasome, the scientists were helped by an enigmatic guide: a mysterious protein called NLRP10. In the center of each inflammasome there is a sensor. Although the sensors differ from each other, depending on the type of threat that they detect, they all belong to the same family of sensing proteins. But as in every family there is also the "black sheep": the NLRP10 protein that lacks the sensing component that characterizes the other members. And what is the benefit of a smoke detector without a sensor?

Prof. Alinev's group, led by Dr. Danping Chang, Dr. Gayatri Mohapatra and Dr. Lara Kern, tried to solve the puzzle of the recalcitrant protein. Using genetic engineering, they created mice that lack the protein in the intestinal lining, and in a series of experiments compared them to normal mice. The comparison revealed that contrary to expectations and similar to the rest of its family members, NLRP10 also forms an inflammasome around itself - a new and unknown type of inflammasome - and has sensing capabilities even without the classic sensing component. This unique inflammasome specializes in sensing damage to the mitochondria - the powerhouses of the cell and the first organelles that are damaged in the event of infection or tissue damage. When the mitochondrial activity goes wrong in the cells in the tissue, the NLRP10 inflammasome receives the distress signal and activates a local immune response that leads to the death of the damaged cells.

Even more intriguing than the discovery of a new inflammasome is its possible involvement in the prevention of inflammatory bowel diseases. These diseases are usually caused by primary damage to the intestinal mucosa leading to the fact that parts of the intestinal tissue that do not normally come into contact with the intestinal bacteria are exposed to them. This exposure may lead to a much more acute inflammatory reaction - a reaction that, if not stopped quickly, may develop into serious damage to the tissue. In the study, the scientists showed that mice without an active NLRP10 inflammasome in the colon lining were much more likely than the control mice to develop severe or even fatal inflammatory bowel disease after initial damage to the lining.

And meanwhile at the University of Bonn, Prof. Letz and his group approached the same questions from a completely different direction: the expression of the same protein in the skin tissue. Their conclusions were similar: they showed that NLRP10 knows how to sense the damage caused to mitochondrial organelles in skin cells as well. Moreover, the findings of the German group also indicated a possible involvement of the inflammasome in the prevention of inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis.

"Our discoveries sharpen the understanding that mucosal cells, such as the lining of the intestine or the skin envelope, are actually cells of the immune system, and they constitute the first line of defense against dangers and invaders from the outside," says Prof. Alinev. "Our next step will be to find out how the inflammasome that we discovered in humans works. If the findings discovered in mice are reproduced, the way may be paved for new drugs for inflammatory diseases of the skin or intestine."

Dr. Yiming Ha, Dr. Mirav Shmoeli, Dr. Raphael Valdes Maas, Dr. Alexandra Kolodzika, Miguel Camacho Rupino, Emmanuel Cheda, Sandy Shimshi, Ryan James Hodgetts, also participated in the study. Dr. Meli Dori-Bachsh, Dr. Christian Klimayer, Kim Goldenberg, Dr. Melina Heineman, Dr. Hagit Shapira, Prof. Yifat Marble and Dr. Sohaib Abedin from the Department of Systemic Immunology of the Weizmann Institute of Science; Dr. Tomesh Proshniki, Matilda B. Vasconcellos and Prof. Aika Letz of the University of Bonn; Lena Schur, Franziska Hertel, Ye Saul Lee, and Dr. Jens Puschhof from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany; Dr. Noa Stettner and Prof. Alon Hermlin from the Department of Veterinary Resources of the Weizmann Institute of Science; Prof. Minho Chen from Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China; and Prof. Richard E. Flavel from Yale University School of Medicine.