Bacteria that are carried in the air for great distances on particles land in part on the ground while they are alive - and ready to multiply

Bacteria, viruses and other microscopic creatures migrate around the world effortlessly. Due to their tiny size, winds carry them on top of dust and other particles across continents and oceans. Many researchers, including Weizmann Institute of Science scientists, have been documenting these journeys for years by detecting genetic material in air samples, but a crucial question remains open: what is the condition of the microorganisms that land after sailing for long days in conditions of low temperatures, extreme dryness and strong ultraviolet radiation, and whether Are they capable of multiplying and influencing humans, plants and animals in the new place they arrived at?

מNew research in the laboratory of Prof. Yanon Rodich From the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the Weizmann Institute, it appears that at least some of the bacteria carried by the wind reach their destination while they are alive and able to "settle" in a place and multiply - findings that have implications for human health as well as the health of plants and farm animals. "It is known that being outside during a dust storm is harmful to health. Now we also know that these storms carry live bacteria in their wings", says Prof. Rodich. "In light of the expected increase in the frequency of dust storms in the era of climate change, it is possible that the new findings will allow in the future to warn against storms in a targeted manner to different populations, such as the immunocompromised or farmers."

Unlike most of us, who want to avoid dust storms whenever possible, Arkurkamaz chased them for months. As luck would have it, during the research period several of them visited our area on weekends. Thus he found himself spending time alone on the roof of the laboratory on Saturdays and holidays - including in the wee hours of the night

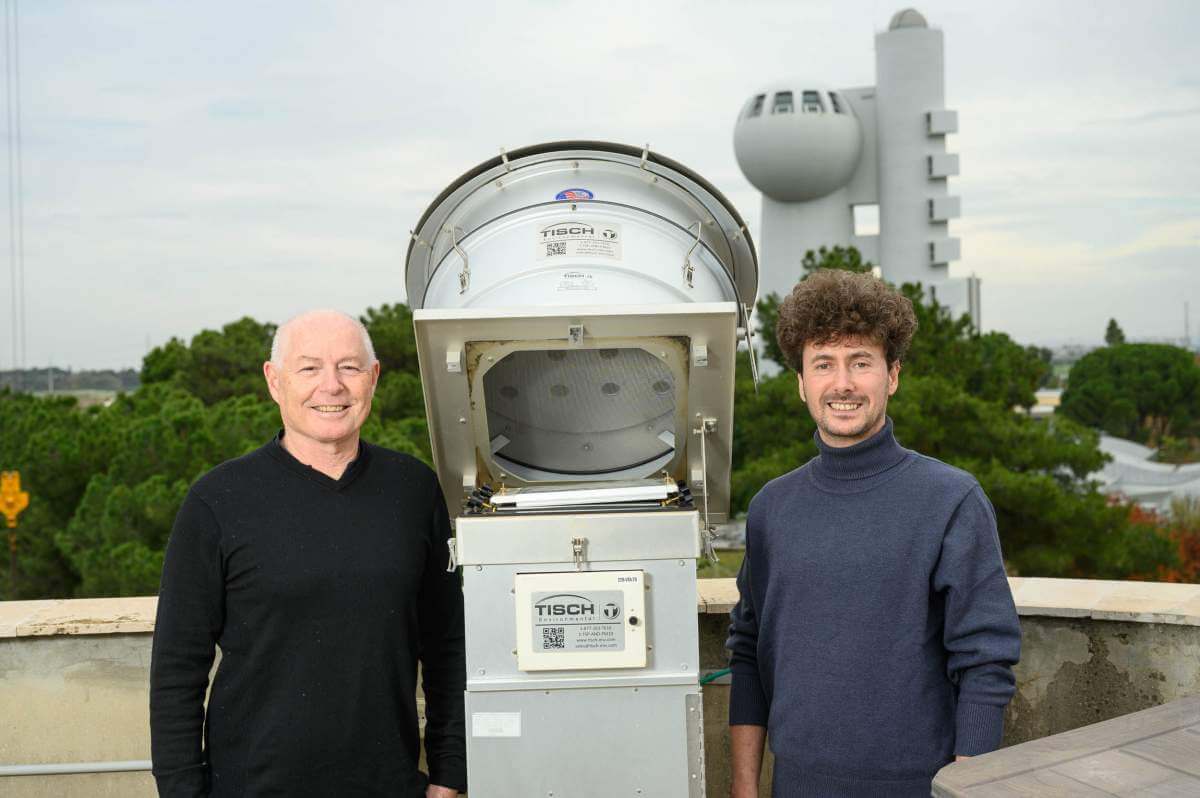

The Eastern Mediterranean region, which has served as an important traffic route for humans since the dawn of civilization, is particularly suitable for studying the aerial journeys of microorganisms. These creatures arrive in our region on a bed of desert dust from the four wings of the region: from the Sahara, from the Arabian Peninsula, from the Syria-Iraq border and Europe. The new research - led by Burak Adnan Erkurkamaz, who himself came to the institute from another Mediterranean country, Turkey - is based on air samples collected in Israel during dust storms and between storms using instruments installed on the roof of Prof. Rudich's laboratory. After collection, the samples were separated into different sizes in order to locate genetic material in them. Since DNA molecules are relatively durable and live longer than their owners, the scientists also looked for another type of genetic material, whose "shelf life" is much shorter: RNA molecules that are copied from DNA for various functions in the cell. A high ratio of RNA to DNA can indicate that genetic activity is occurring in the cell or has recently occurred. In other words: these are signs of life.

"Our assumption was that if we found more RNA than DNA in a bacterium, this means that this bacterium is alive or was alive until very recently," says Erkurkamaz.

Erkurkamaz and Dr. Daniela Gat, also from Prof. Rodich's laboratory, located no less than 5,000 species of bacteria in the air samples. RNA sequencing showed that about 10% of all the bacteria found in the samples were alive. Some of them were bacteria causing diseases in humans, animals or plants, such as the genus Pseudomonas which includes several species that cause infections in humans and farm animals. Other types found in the samples are involved in various biochemical processes: for example Sphingomonas bacteria, various species of which are involved in the fermentation of grapes used to make wine, or Methylorobrom bacteria, some of which affect the ripening of strawberries and their taste.

The researchers also discovered that the larger the particles in the storm, the greater the chance of locating larger and more diverse bacterial populations. These findings may affect the perception of the risk posed by dust storms, since today smaller particles are often seen as more dangerous, due to their ability to penetrate deep into the lungs. Moreover, the "love" of bacteria for large particles also hints at the way in which they survive the arduous journey: apparently, they "catch a ride" on desert dust particles or they themselves gather together into aggregates, i.e. particles, in a way that protects them from the dangers of the journey - similarly To the way in which bacterial colonies isolate themselves from a hostile environment with the help of a thin coating known as a biofilm. Indeed, Arcorquamase showed in a study that the bacteria in the samples that were most likely alive belonged to species known to form biofilms.

The researchers also traced the origin of the different bacteria by tracking wind paths during dust storms and cross-referencing satellite data on these storms with the dates the samples were collected. Their findings showed that the composition of the bacteria in the samples changed depending on the place from which the dust took off on its way.

Unlike most of us, who want to avoid dust storms whenever possible, Arkurkamaz chased them for months. As luck would have it, during the research period several of them visited our area on weekends. Thus he found himself spending time alone on the roof of the laboratory on Saturdays and holidays - including in the wee hours of the night. But Erkurkamaz is not complaining. After all, the view was spectacular and perhaps more importantly - the investment paid off. "Our findings shed new light on the environmental consequences of wind-borne bacteria," he concludes.

More of the topic in Hayadan: