Is smoke rising over South Australia responsible for pink sunsets in South America? in the article published today in the scientific journal Science, reveal Prof. Ilan Koren And Dr. Eitan Hirsch that millions of tons of smoke particles from the great wave of fires in Australia drifted up to the upper layer of the atmosphere and covered - for months - the southern half of the globe, dimmed the sunlight and cooled our planet. The environmental effects of the event are similar to the consequences of a powerful volcanic eruption.

In January 2020, Prof. Koren, from the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the Weizmann Institute of Science, and Dr. Hirsch - a former student of Prof. Koren and currently head of the Environmental Sciences Research Area at the Israel Biological Research Institute - noticed a serious deviation in the indicators that monitor the particle load in the atmosphere. These indicators, based on satellite data, showed a deviation three times larger than normal - one of the highest figures ever, higher than the eruption of the Pinatubo volcano in the Philippines in 1991. Since no volcano erupted in January 2020, scientists wondered if it was possible to blame the heavy wave of fires that hit Australia at the end of 2019 and subsided in 2020 - although the cases where fire smoke penetrated through the lowest layer of the atmosphere are rare; This layer, called the "troposphere", starts at the ground and reaches a height of several kilometers. In a normal situation, if smoke particles manage to rise to the top of the troposphere, they are stopped at the "tropopause" - the layer of the atmosphere that separates the troposphere from the upper layer of the atmosphere: the "stratosphere".

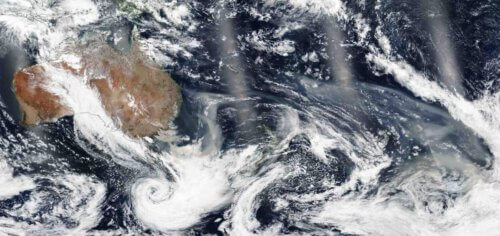

A careful examination of data received from various research satellites showed that the source of the particles is indeed fires in Australia, especially those that burned in the southeast of the continent. An in-depth analysis of the satellite data even showed that a wide band of haze in the upper layer of the atmosphere covered the entire southern hemisphere - a phenomenon that reached its peak between January and March 2020 and continued until the end of July. During this period the smoke moves around the world at the latitude of Australia, when it completes the entire coffee in about two weeks thanks to the uniform and strong winds in the stratosphere.

How did the smoke particles breach the tropopause ceiling and what was special about the last wave of fires that allowed them to do so? "One clue," says Dr. Hirsch, "can be found in another forest fire that happened a few years ago in Canada." Even then, high levels of particle load in the atmosphere were recorded. This fire, like the fires in Australia, also occurred far from the equator. The height of the lower atmosphere layer shrinks at these latitudes: over the tropics it reaches up to 18 kilometers above sea level, but at the northern and southern edges the maximum height is 10 kilometers. So, the first factor that allowed the particles to cross the tropopause lies in the simple fact that the distance there was shorter.

The formation of the clouds does not explain the huge amounts of smoke particles in the upper atmosphere

Fire clouds - clouds that are formed as a result of fires - are how smoke may reach the upper atmosphere. But when they examined satellite data, the scientists discovered that the fire clouds formed only for a fraction of the duration of the fires, and they were observed mainly above those that burned in the central part of the coast. That is, the formation of the clouds does not explain the huge amounts of smoke particles that accumulated in the upper layer.

The second factor, then, that allowed the smoke particles to find their way to the upper layer is the weather patterns in the strip surrounding the southern tip of Australia - one of the windiest areas on Earth. The stormy wind carried the smoke particles towards the Pacific Ocean, where they merged with clouds that lifted the smoke within them to the upper layer.

When the particles crossed the tropopause, they discovered another world. If below they were at the mercy of the different and opposing air currents, in the upper layer the air moved in a uniform, linear and ceaseless manner, which led them eastward - over the ocean, through South America and the Indian Ocean, and back to Australia. "People in Chile breathed in smoke particles that made their way from Australia," says Dr. Hirsch.

"For the common man, it seemed that the air was warmer and that the sunsets were redder than usual," says Prof. Koren. "But in practice the sunlight is blocked, as happens in volcanic eruptions. Therefore the final result of the dispersion of the smoke particles in the upper layer is the cooling of the atmosphere. The consequences for the marine environment and the climate are still unclear."

"There are always fires - in California, in Australia, in the tropics," he adds. "We may not be able to stop the fire, but we must understand that the exact location where the fire burns has a decisive influence on the climatic effect."

More of the topic in Hayadan: