Weizmann Institute of Science scientists have uncovered an unusual mechanism of cell death. The findings may lead to new treatments for various diseases

A lightning strike or a coconut falling from the tree - it is impossible to prepare in advance for unusual death scenarios. In our body cells, on the other hand, even unexpected death scenarios were not left to chance. It appears fromNew research of Weizmann Institute of Science scientists who for the first time revealed in fly embryos a molecular mechanism of an abnormal cell death pathway known as "parthanatos".

The common pathway of programmed cell death is apoptosis, but apart from it there are other death pathways. Understanding these pathways may allow new treatments for many diseases. For example, chemotherapy or radiation treatments are designed to kill cancer cells through apoptosis, but most cancer cells are less sensitive to this pathway and therefore a bypass death pathway is required. In Parkinson's disease, on the other hand, it is desirable to block the alternative death pathway of the parenthetus type, since recent studies suggest that this is how the nerve cells die in this disease. Parthentus - whose name is derived from Thantus, the personification of death in Greek mythology - is also involved in stroke, heart disease and diabetes.

Scientists have so far identified about a dozen different cell death pathways in cell cultures in the laboratory, but it is difficult to know which of them actually occur in living organisms and how. Prof. Eli Arma The Department of Molecular Genetics and members of his group set out to complete the missing knowledge by observing fruit fly embryos. About a third of the early germ cells in these embryos - the cells from which the sperm and egg cells in the adult fly will be formed - die during their migration in the developing embryo. previous researches It was shown that they do not die as a result of apoptosis, but the cause of death has remained a mystery for two decades.

In living things, cell death is a matter of life and death. That's why our cells have a rich repertoire of ways to kill themselves - where each way suits different needs

To check if this is one of the alternative death pathways, the research team, led by the post-doctoral researcher Dr. Lama Traira-Abrahim, because the germ cells do not die through apoptosis. The researchers showed that even when all seven enzymes identified with apoptosis and called caspases were blocked, there was no change in the death rate of the germ cells. On the other hand, the genes found to be involved in the process pointed an accusing finger towards another death pathway - paranthos, which so far has only been documented in cell cultures or in mouse models for diseases such as ischemic stroke.

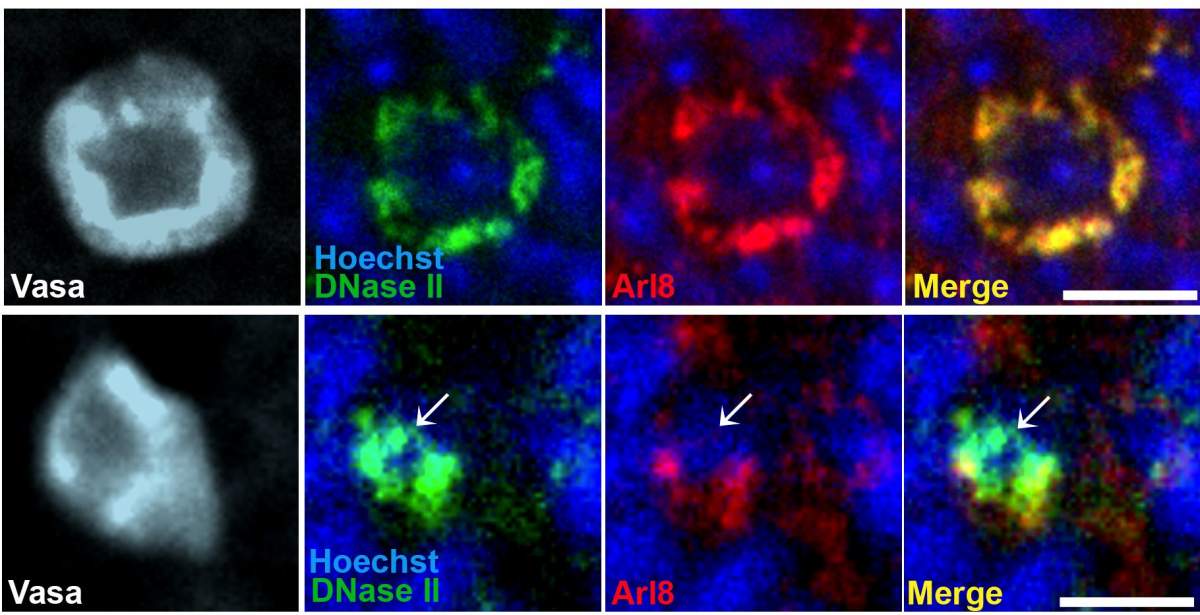

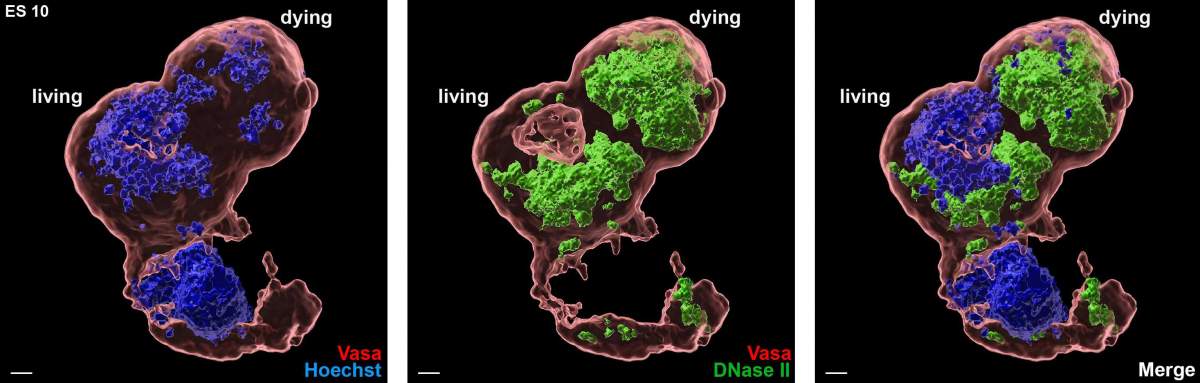

In order to confirm that it is indeed Parathantus, Dr. Traira-Abrahim and her colleagues conducted experiments on transgenic flies. They used antibodies to find where the proteins produced by the genes identified with Parenthetus are located, blocked some of the molecular signals and conducted additional tests which confirmed that the cause of death is indeed a unique pathway of Parenthetus. These experiments allowed the scientists to reveal the complete biochemical pathway of this cell death and to identify three main molecules involved in it: PARP-1 and AIF and the DNA cutting enzyme DNase II which was a big surprise since it is normally found in an organelle called a lysosome.

But why was this pathway created during evolution? And why do the germ cells "choose" it instead of the more common apoptosis pathway? Prof. Arma believes that the answer lies in caspases - the enzymes responsible for apoptosis. Studies in his laboratory have previously shown that a low level of activity of caspases is responsible for essential actions that are not related to apoptosis, including the blocking of cell migration. "If the caspases were in the picture, they could disrupt the migration of all the germ cells and harm the development of the embryo. Evolution probably prevented this by means of an alternative death pathway that does not involve caspases, that is, by means of parathanos."

In living things, cell death is a matter of life and death. That's why our cells have a rich repertoire of ways to kill themselves - where each way suits different needs. The details of the parenthetus pathway revealed in flies will form the basis for the study of this alternative pathway also in mammals and in various disease states in humans. "We have shown that parenthos is a process of programmed cell death that occurs in living things," says Dr. Traira-Ebrahim. "This means that its molecular mechanisms can be activated in the body. Such activation can enable more accurate and efficient cell killing than existing drugs."

Alital Chas Morris, Guy Hadari, Sharon Ben-Hur, Dr. Alina Kolpakova, Tsliil Brown and Dr. Keren Yacovi-Sharon from the Department of Molecular Genetics and Dr. Yoav Peleg from the Department of Life Science Research Infrastructures participated in the study.

More of the topic in Hayadan: