The coming Tokyo Olympics arouses L's curiosity "Why are records constantly broken at every Olympics or World Championships?"

Baron Pierre de Coubertin who renewed the Olympic Games in the modern era also coined the slogan accompanying them Citius, Altius, Fortius: faster, higher, stronger. Indeed, what is an Olympics or a world championship without the dramatic call "And this is a new world record" at the end of a final. But, as the records improve, it is hard not to wonder when the person will reach the end of his ability; Which running records will force the Olympic Committee to give up the first word in its motto?

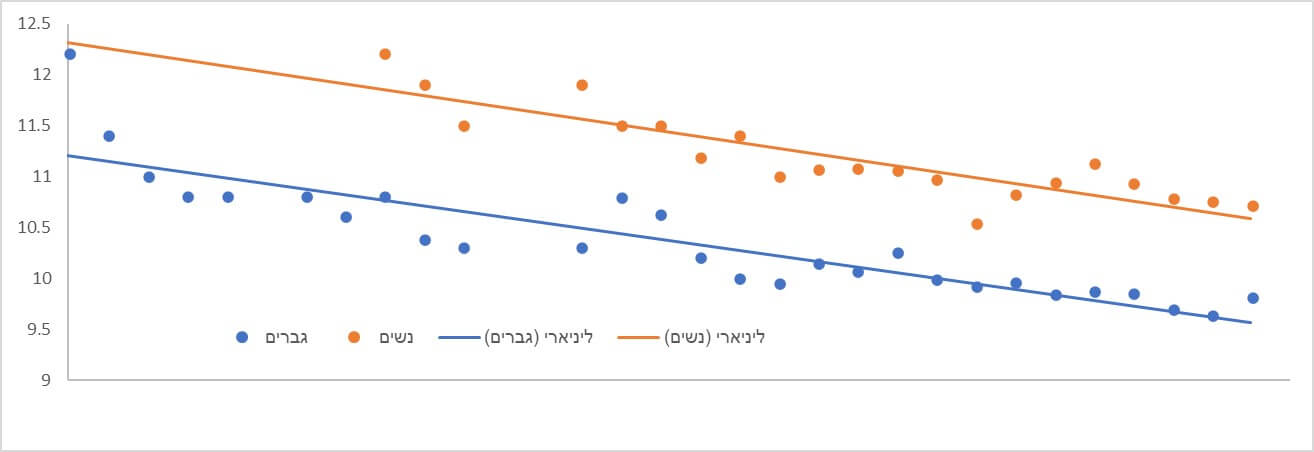

There are those who think that the stock of new records is unlimited. In 2004, the biologist Andrew J. Tatem published an amazing article in its simplicity: one page and in the center a graph with two straight lines. The points represent the best result in the final race in the 100 meter run from the Paris Olympics in 1900 in which Frank Jarvis from the USA won the gold with a result of exactly 11 seconds (an improvement of a full second compared to the first Olympics in 1896) until the Athens Olympics in 2004. If we believe Tetem the improvement in results is permanent (linear) in time and the rate of improvement is faster in the women. As such, the lines can be extended and the future anticipated. Feminists should wait for the 2156 Olympics when the female record is expected: 8.079 seconds to finally achieve the predicted male record, according to the graph to be 8.098 seconds. The lines drawn by Tatem in 2004 predicted with reasonable accuracy the achievements of the Beijing and London Olympics 4 and 8 years later and it is tempting to believe that our descendants will get to see much more quality competitions than us.

But, as expected, simplistic predictions of this kind are not agreed upon in the scientific community, there is no reason to assume a uniform rate of improvement and in fact there are excellent reasons to assume that the rate of improvement must decrease - the continuation of the straight line without a limit means that the winner of the 100 meter race in the 2892 Olympics will reach the finish line 2 hundredths of a second before The jump shot.

Indeed, there are those who draw graphs that progress to an asymptote, meaning a peak value that can no longer be broken due to the limitations of the human body. When you check the development of achievements over the years in a wide variety of sports, you can indeed see a moderation in the pace of improvements. Until the XNUMXs, the graph depicting the number of world records broken in each championship was a rising line that crashes with the world wars but continues to qualify after them.

In the 80s the line stabilizes and in the mid-90s it is in a clear downward trend. The rate of improvement in records (by what percentage did the record breakers improve the record that was broken) is steadily decreasing: the record breakers from the 19s and 3s of the 2027s offset on average almost 99.95% for each record breaking, while today's records improve about XNUMX percent of the result. The person who compiled the statistics predicted that already in XNUMX half of the records will reach XNUMX% of the best possible value. This means that we are the last generation to see athletics records being broken.

Alan M. Nevill, who examined the development of the world records in the medium and long runs, found that the period of time between the late 40s and the mid-800s was the golden age of running in which the world records improved rapidly. This is the period when athletics became professional and training methods were perfected. In those years, new populations in the world were exposed to competitive sports and the human pool from which outstanding athletes can be identified grew. Since the 1500s, the rate of improvement in running disciplines has decreased for distances of 1980 meters and more. Thus, for example, the world record for women in the 1993 meter run set in 16 was kept until 3 when it was improved by only two seconds and has been holding since then for 10,000 consecutive years. According to Neville's analyses, the record for men in this profession is only 10 seconds away from its final value and in the XNUMX meters run, an improvement of only XNUMX seconds can be expected.

Neville predicts boredom for us, but a study of the tables and graphs of the development of world records brings up fascinating surprises. The world records in several branches are progressing in a way that challenges not only those who try to understand the mechanisms but also those who just try to describe the process. The women's record in swimming for 400 meters rowing, for example, improved rapidly from the 20s of the last century and stabilized in the early 1988s, then the peaceful asymptote was broken in a burst of world records throughout the 2006s to reach absolute stability again from 4 until 2016, when it returned to be improved by 3 swimmers until the world record in the XNUMX Olympics Whoever collected and arranged the data had to describe it with two different mathematical equations. Such strange behavior appears in other athletics and swimming disciplines and in weight lifting the graph even shows XNUMX periods of rapid increase after a record that seems to be "the limit of ability" has already stabilized.

You have to be very naive to believe that the science of chemistry has nothing to do with the emergence of new limits to human ability, it is difficult to explain otherwise the decline in the results of subjects such as putting an iron ball from the 10,000s to today. But even the optimists who believe that the future holds more exciting peaks that come from real ability and not from steroids have interesting reasons. Examining the progress of world records over the years shows that the chance of breaking a record depends mainly on the appearance of a successful athlete, during the peak of his career to break the world record several times and bring him to a new period of stability. In the 39 meter run, for example, the world record has been broken 1911 times since the competitions began in 287, and a total of 4 seconds have been cut since then. It turns out that most of this improvement was achieved in the legs of only 53 gifted runners. The legendary Pabo Normi who cut 20 seconds off the time in a series of races in the 50s, Emil Zatopek, the "Czech Locomotive", who woke the profession from its slumber in the early 40s and cut 90 seconds off the record, Ron Clark in the mid-70s and Hajla Gavrislasi in the XNUMXs completed two bursts of excellence over XNUMX % of the overall improvement in the industry.

This pattern of progress is repeated in many professions: a world record will be broken when someone appears whose physical data, and in particular his ability to absorb oxygen and efficiently use the energy stored in the muscles, surpasses all his predecessors. Alun Williams went to the trouble and counted no less than 23 genes whose changes affect athletic ability.

The geneticist I. Ahmetov expands the list to no less than 36 known genes. In this group are genes related to oxygen binding, blood circulation control, muscle cell metabolism, mitochondrial function (the energy organ in the cell), movement efficiency, and more. Since the prevalence of the "good" variations of each gene in a population is known, it is possible to calculate the probability that a single person will receive the perfect set of all 23 genes in the genetic casino. Since the frequency of some of the superior genes is quite low, the chance of finding such a super athlete among the 6 billion inhabitants of the earth is 0.0005% (it takes 20,000 worlds like ours to find one such person). Williams' statistical analysis shows that among humans living with us, one can expect, at most, a person who received 17 optimal genes out of the 23. Each generation reshuffles the genetic cards and creates, therefore, a chance to find a new talent in it so that the "peak of human ability" is still far from us.

Williams focused on sports that require endurance and high consumption of oxygen, such as the long runs. For other branches, a different physiology and a different set of genes are required to break records. In running 100 meters, the muscle utilizes the energy and oxygen already present in it before the jump, and the oxygen transport system is less important compared to the ability to accelerate quickly, that is, the maximum power that the muscle is capable of producing (an addition of 10% to this power will, according to the calculations, bring the world record to approximately 9.3 seconds) . The series of important genes is different, but the chances of getting a genetically optimal 100 meter sprinter are no less zero.

Williams' approach has been criticized because it ignores the psychological abilities required of an elite athlete. The ability to transport oxygen to the muscles and efficiently create kinetic energy there will not result in breaking world records without the mental fortitude required for a grueling training regime and the intelligence required for an intelligent distribution of power throughout the race. This psychological ability also depends on genetics and no less on the environment in which the athlete grows and the type of training he receives.

Another way to improve achievements is to change technique. This is how the world record in the high jump, which did not advance for a whole decade, jumped from the beginning of the 70s when the Fosbury jump (in which the jumper turns his back to the bar) replaced the old belly roll technique. Recently, Japanese scientists suggested that the world record in the 100-meter dash may be broken precisely by moving on all 4 limbs. Kenishi Ito, a Japanese athlete breaks Guinness records by "running" 100 meters on his feet and hands. This run looks (For example in this video) Strange but a biomechanical analysis of this movement yielded a prediction that in 2048 (7 more Olympics) an athlete will be able to determine a result of 9.28 seconds using his palms. To do this, the way of running will not be as an imitation of a galloping horse as the current Shi'an moves, ie left leg-right leg-left hand right hand, but in a sequence of movements similar to the running of a cheetah: left leg-right leg-right hand-left hand. In addition, the same theoretical athlete will have to take wider steps and side-to-side movements (if the researchers' simulations are to be believed, movements that are in the realm of human muscle capacity and flexibility). Even if we don't get to see human cheetahs on the track, the possibilities of genetics and alongside the improvement of equipment (and chemistry) guarantee that even in the next Olympics, athletes will amaze the audience of couch potatoes by breaking the "limit of human ability".

Did an interesting, intriguing, strange, delusional or funny question occur to you? sent to ysorek@gmail.com

More of the topic in Hayadan:

2 תגובות

Perhaps when chemistry reaches its limit, genetic editing will arrive.

It will be difficult to prove whether the athlete's genes came to him naturally or not.

I personally don't find much interest in people "scratching the human ability" in sports, it is more true that they are scratching their health, and the ability of pharmacology to produce substances that contribute to being discovered in tests.

very interesting

It is clear to me that there is constant improvement mainly thanks to technological changes / methods / style

And I completely ignore the matter of the use of "additives" of all kinds...

I loved the article!!!