We don't know everything - but that doesn't mean we don't know anything

What do tobacco, food additives, chemical flame retardants and carbon dioxide emissions have in common? The industries associated with them, and their harmful effects, have worked with remarkable consistency and disturbing effectiveness to sow public doubt against scientific evidence. I call it pseudo-skepticism.

It started in the tobacco industry, when scientific evidence began to accumulate that cigarettes cause lung cancer. In a memo from 1969, this statement appears from the mouth of a manager at the Brown & Williamson tobacco company: "The product we market is the supplier. This is the best means available to us in the competition against the 'totality of evidence' rooted in public opinion." In one example, among many, of the way doubt was sown, an executive at the Philip Morris tobacco company told a committee of the American Congress: "Anything can look harmful. Even applesauce is dangerous if you eat too much of it."

Other industries have imitated the tobacco industry's model. As Peter Sperber, a veteran tobacco industry lobbyist, said: "If you can 'move tobacco' you can do almost anything in public relations." It seems as if everyone is following the same script and using the same exercises, such as: denying the problem, reducing its scope, demanding more evidence, shifting the blame, choosing only the data that suits you, "shooting the messenger", attacking the alternatives, hiring friendly scientists for industry, to establish straw organizations.

Documentary filmmaker Robert Kenner came across the latter method when he filmed his film "Food Ltd", released in 2008. And so he says: "We constantly came across organizations such as the 'Center for Freedom of Consumption' who did everything they could to prevent us from finding out what was in our food." Kenner called them "Orwellian" organizations because these straw organizations looked like neutral, non-profit think tanks interested in uncovering scientific truth, but in fact they were funded by for-profit industries related to the problems these organizations were supposedly researching.

Take for example an American organization called "Citizens for Fire Safety." It is a straw organization founded and partially funded by chemical and tobacco companies to address the problem of fires in private homes, caused by burning cigarettes. Kenner discovered this organization while filming his film "Merchants of Doubt" released in 2014 and based on a book of the same name, from 2010, by historians of science Naomi Oreskes and Eric Conway. (I am interviewed in the film.) In order to mislead the legislators and divert public attention from the connection between cigarettes and fires in private homes, the tobacco industry hired Sperber to work in cooperation with the National Association of Fire Chiefs in the US in order to promote the use of flame retardants Chemicals in furniture. And so it was written in another memo: "Your task is to make the world around the cigarette fireproof." And immediately the American furniture was washed with toxic chemicals.

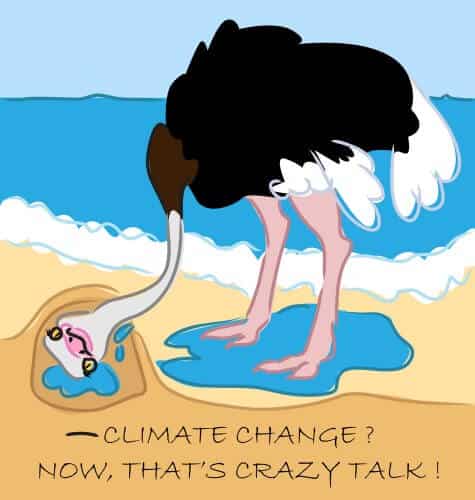

Climate change is the latest arena of pseudo-skepticism, and the current straw organization is ClimateDepot.com, partially funded by the oil companies Chevron and Exxon, and headed by a colorful guy named Mark Murano. And so Murano told Kenner: "I'm not a scientist, but I present myself as one occasionally on TV ... hell, more than occasionally." Murano admits that he has no training in climate science, and in order to cast doubt on them, he makes sure that his words are always "short, simple and funny." His method also includes mocking climate scientists such as James A. Hansen of Columbia University. "You must not be afraid of face-to-face metaphorical combat. And you have to name names, and you have to go after certain people," he says, adding with a wry smile, "I think that's what I enjoy doing the most."

It is not difficult to generate doubts because in science all conclusions are conditional, and skepticism is an inherent part of the process. But as Orseks says, "Just because we don't know everything, doesn't mean we know nothing." Actually, we know a lot, and the things we do know are the things some people don't want us to know, and that's the heart of the problem. What can be done against this pseudo-skepticism?

In the movie Merchants of Doubt, the juggler Jamie Ian Suisse, known for his eye catching and sleight of hand shows, offers an answer: "Once something is revealed, it can never be hidden." He demonstrates this with a card trick where a card chosen and returned to the deck finds itself under a drinking glass on the table. It's almost impossible to see how this is done, but once the move is illuminated on replay, it's almost impossible to miss it later on replay. The goal of proper skepticism is to reveal the secrets of the dubious skeptics so that the magic behind their tricks wears off.

About the author

Michael Shermer is the publisher of Skeptic magazine (www.skeptic.com). His new book: "The Moral Noah's Ark" was recently published. Follow him on Twitter: @michaelshermer

Editor's Note: This looks exactly like what the Haifa Municipality and even the Association of Cities for the Environment tried to do in the context of The incidence of cancer among children as a result of the air pollution in Haifa in the last week.

The article was published with the permission of Scientific American Israel