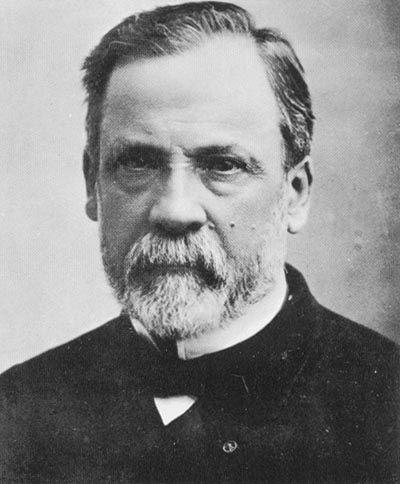

In continuation of the series on spontaneous creation, we are bringing in the coming days a continuation series - this time on the life and work of Louis Pasteur, the man who finally eliminated the validity of this theory that dominated science for many years and hindered its development

For the previous chapters in the spontaneous formation series:

First chapter - the spontaneous formation at the beginning of history.

second chapter - Part a' and part B - The spontaneous formation in the 18th century.

The 19th century was full of medical, scientific and industrial breakthroughs. Charles Darwin brought for the first time a detailed explanation full of evidence for the theory of evolution, in his famous book 'The Origin of Species'. Gregor Mendel deciphered the basics of genetics, which accompany us to this very day. Alexander Volta showed the power of electricity and created the first primitive batteries. Thomas Edison lit up the world with the first light bulb. Thanks to the efforts of many chemists, the existence of the molecules and atoms of which the various elements are made was proven for the first time, and so on and so forth.

The above discoveries and inventions are only the tip of the iceberg as far as the 19th century is concerned, and they reveal to us years rich in science and discoveries. But even among all those researchers and inventors, Louis Pasteur managed to stand out as one of a kind and one of his generation.

Pasteur's discoveries and research dealt with almost all fields of science and industry in his generation. He discovered the chirality (directionality) of molecules, thereby bringing about a new understanding of the science of biochemistry. He saved France's wine industry and turned it into the alcohol powerhouse of Europe. The model of spontaneous formation, which remained strong and existed in the previous centuries, could not resist him. When France's silkworms suffered from a disease that threatened to paralyze the silk trade, Pasteur and his suitcase of microscopes were called for help and together they restored the entire silk industry in France. The anthrax epidemic, which killed millions of sheep and cows throughout Europe in the 19th century, could not resist the vaccine he developed. Even rabies, which removes the foggy dock of reason from human minds and turns them into murderous savages, succumbed to Pasteur's medical ingenuity.

When we try to analyze Pasteur's personality, there are many documents and letters that reveal to us the intricacies of his heart. But I believe that out of all these, one testimony in particular can teach about the extraordinary character of that person. From just one paragraph of a letter he wrote to his son's daughter-in-law who threatened to come to visit Paris, we can infer a whole world:

"I beg you to reconsider, my dear madam, on account of my health, which I take great care of, and also because you make me the most miserable of all human beings when I see you arriving in Paris for a visit which you initially say will last only a few days, but I know that it will certainly last for several weeks . It will put me in a very nervous mood.”

There is no doubt that above all his other qualities, Louis Pasteur was a brave and persistent man who stuck to his principles and ideas and refused to give in to popular opinion. He was absorbed from morning to night in research in his laboratory, and as we can understand from the quoted letter he hated to stop his work even to consider other people's needs or his own private needs. Surprisingly, despite these qualities, he and his wife had a long and happy married life and throughout all his years she was a help against him.

It is difficult to describe the entirety of Pasteur's work in one chapter, so in this chapter we will only talk about Pasteur's first twenty years in science. Although the areas in which he did business and research seem very far from each other, they actually form a logical chain of difficulties and conclusions that accompanied Pasteur throughout his life. In this chapter we will see how he moved from his research in chemistry to deal with the problem of fermentation of wine and beer in France, and from there he arrived at the great riddle of spontaneous formation, which he solved unequivocally. In the following chapters we will talk about his other discoveries, including the vaccine he developed for rabies and anthrax.

Young Pasteur

Pasteur was born on December 22, 1822, in the small town of Doula in France. His father was a surgeon in Napoleon's army, and returning home to take care of his family, he became a humble tanner. Although he himself lacked any real education, he strove to give his son the education he was denied. His dream was for his son to become a teacher at the local school, but the young Pasteur showed no signs of excessive intelligence, preferring to spend his time fishing and painting rather than sitting in the classroom. His father was displeased, to say the least, with Pasteur's desire to become an artist when he grew up.

He took every means at his disposal in order to restore Pasteur's interest in the school, voluntarily or out of necessity, and finally succeeded in arousing the young scholar's interest in the science of chemistry. The young Pasteur immersed himself in the sciences and became an enthusiastic student, and even graduated from high school with honors. Although his father believed that he would not succeed in more than a teaching position, Pasteur made a strong impression on the principal of the school where he studied, and this convinced Pasteur and his father that the young man should try and be admitted to one of the most prestigious academic institutions in France - Ecole Normale Suprieure in Paris. This university was intended solely for the development of academic researchers in the fields of science. "France needs young scientists, who will help rebuild it after the war," must have been one of the arguments used by the manager, when he argued with the father who did not want to send his son far away. The father, who was a great patriot and a staunch admirer of Napoleon I, submitted to the decree, "For the good of France!" And young Pasteur was sent to university almost against his will.

In the next part we will expand on the experiences of the young Pasteur in the academic world, and how he broke ground for the science of biochemistry and crystallography as we know it today.

Part II of the article

Part III of the article

Part D of the article

4 תגובות

Thanks for the articles. Unfortunately, there is too little information about Pasteur in Hebrew, even the entry in Wikipedia today (2016) is a little more than a little more than a little bit more, it seems that our culture has a short memory if we cherish so few important scientists like Pasteur and his fellow disease researchers who changed the reality where about half of the children do not reach to the age of maturity.