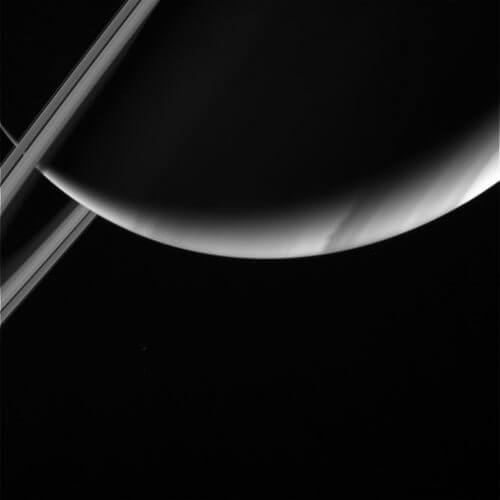

Contrary to researchers' expectations, the Cassini spacecraft, which last week plunged for the first time into the narrow space between Saturn and its ring belt, recorded very few dust and ice particles in the mysterious region, which had never been studied before.

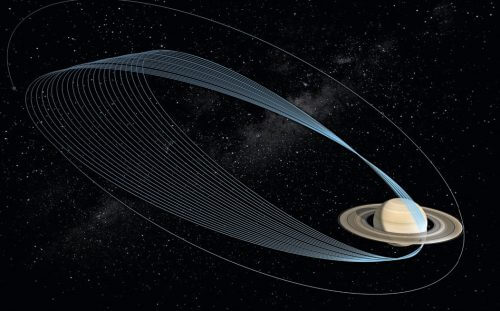

On April 26, the Cassini spacecraft dived for the first time into the gap between Saturn and its rings, after recently entering a unique orbit in which it passes through the narrow gap, which is about2,400 km. This is the last stage in the life of the old spacecraft, which was launched into space in 1997 and arrived at Saturn in 2004, at the end of which it will burn up in the giant planet's atmosphere.

During the dive into the space, which no other spacecraft has visited before, the spacecraft recorded far fewer dust and ice particles than the researchers expected, despite being very close to Saturn's rings.

Researchers still have no explanation for the mystery, but it is good news for mission engineers, who feared collisions with small particles during the daring dives.

"The region between the rings and Saturn is the 'big space,' apparently," said Cassini project manager Earl Mays of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). "Cassini will remain in orbit while scientists work on solving the mystery of a much lower than expected dust level."

The biggest fear of the engineers from the transition in the gap was collision with small particles originating from the rings. At Cassini's enormous speed when passing through space, over 120,000 km/h, even a collision with very small particles can cause damage to the spacecraft's sensitive scientific instruments.

Although from the beginning the researchers estimated that the amount of particles in the space would not be dangerous for the spaceship, they preferred not to take a risk in the first dive in the space, and therefore directed the antenna plate of the spaceship (which is 4 meters in diameter) towards the direction of its movement, in order for it to serve as a shield against collisions with particles.

Now that the researchers know that the risk of collision with small particles is even lower than their initial estimate, they will be able to avoid using the antenna plate as a shield. Instead, they will be able to direct the spacecraft's scientific instruments according to the scientific objectives set for each dive.

The spacecraft measured the amount of particles in the space using its Radio and Plasma Wave Science instrument. The device has antennas that extend beyond the spacecraft's main antenna plate, so these could continue to operate even when the spacecraft used the plate as a shield while diving. As particles collide in the spacecraft, they turn into tiny clouds of plasma and create an electrical signal that the instrument is able to measure.

When the information from the radio wave and plasma device is converted into audio format, each collision with a particle sounds like a small explosion. Contrary to their predictions, the mission researchers Listen Very few "pops" during the transition in the gain.

According to NASA, the device measured only a few impacts of particles, the size of which is no larger than that of smoke particles (about one micron - one millionth of a meter). For comparison, when Cassini passed in December 2016 in A thin ring originating from the moons Janus and Epimetheus, the device recorded hundreds of collisions per second with particles from the ring.

"It was a little confusing - we didn't hear what we expected to hear," said William Kurth, head of the radio wave and plasma instrument team at the University of Iowa. "I listened to the data from the first dive several times, and I can probably count on my hands the amount of collisions with dust particles that I hear."

Listen to particle collisions, as recorded by the spacecraft's plasma wave instrument and radio during the dive:

For comparison, listen to particle collisions as recorded by diving through a thin ring in December 2016:

Yesterday, Cassini plunged once more into the narrow space between Saturn and its rings. This time, as mentioned, she did not use her antenna as a shield against collisions with particles, and could direct her scientific instruments more effectively. The spacecraft cut contact with the control center on Earth before the dive, and will transmit the data it collected today, May 3.

The spacecraft will perform a total of 22 spaced dives, in which it will explore Saturn and its rings. Upon completion, on the 22nd dive on September 15 this year, the spacecraft will enter Saturn's atmosphere and burn up as a meteor.

The researchers hope that during the dives the spacecraft will be able to study, among other things, the internal composition of Saturn, by measuring its gravitational field. Additionally, in some of the final dives of the spacecraft, it will come dangerously close to its atmosphere and measure its composition directly.

The researchers also hope to accurately measure the mass of the rings, thereby determining their age. A higher mass than the one currently estimated would indicate that they are very old, and that they may have even formed together with Saturn in the early stages of the solar system; A lower mass would indicate a younger age, and that the rings were formed by a small body, a moon or other object, that came too close to Saturn, was caught in its gravity and torn apart.

Cassini is in excellent condition and can continue to operate for many more years, thanks to a generator that converts heat emitted by radioactive material into electricity, but NASA decided to destroy the spacecraft because the fuel in its main engine is running low. If the spacecraft cannot in the future correct its course using the rocket engine, it may, even if the chance is slim, collide with the moons Enceladus and Titan, where life may be possible. The spacecraft has not undergone a thorough cleaning of terrestrial bacteria that may survive inside it, so such a collision will harm future research on the search for life on these moons.

See more on the subject on the science website: