"Often, people with Charles Bona syndrome are not told about it. It is important that they know that this is a completely normal phenomenon - although their eyes no longer transmit information to the brain, the vision system in their brain is normal and continues to work"

People who have gone blind, and yet - see. This is not an act of miracles, but a neurological syndrome that has been known for more than 250 years and is named after the Swiss scientist Charles Bona, who in 1769 documented his 87-year-old grandfather who suffered from almost complete blindness, but saw clearly and in detail visions of people, animals and buildings that appeared in front of his eyes out of imagination. Charles Bona syndrome was once thought to be rare, but it is apparently much more common than previously thought. In fact, it is possible that many of those who have lost their sight during their lifetime experience this syndrome, but are afraid to share it with their surroundings - for fear of being considered to have lost their minds. However, it is important to emphasize at the outset that this syndrome actually indicates completely normal brain activity - and these hallucinations have no connection or affinity with any mental illness or neurological disease.

These and other findings emerge from a new study by Weizmann Institute of Science scientists who recorded the brain activity of blind people with Charles Bona syndrome - and even translated their visions into videos that were then shown to people with normal vision - all with the aim of understanding the brain basis of this syndrome. The research findings which are published today in the scientific journal Brain, reveal the mechanism responsible for the appearance of these hallucinations and show that both vision that originates from sensory input from the outside world and hallucination that originates in the brain itself, are related to the activity of the same brain areas that create the experience of vision.

Spontaneous resting waves

in the laboratory of Prof. Rafi Malach In the neurobiology department, we are interested in one of the most wonderful features of the human brain - our capacity for spontaneous and creative behavior. The basic hypothesis is that spontaneous behavior is made possible thanks to a mysterious brain activity known as "spontaneous resting waves": extremely slow oscillations of brain activity that occur below the threshold of consciousness. Despite the fact that this is a widely studied phenomenon in the human brain, the question of whether this brain activity is related to behavior is still a mystery.

The ability to test whether spontaneous brain activity leads to spontaneous behavior is extremely limited for several reasons: First, it is impossible to command people to behave spontaneously, and certainly not subjects who are inside an MRI machine. Second, it is difficult to impossible to differentiate between brain activity that originates from environmental stimuli and spontaneous brain activity, which does not arise as a result of environmental stimulation. Since the hallucinations in Charles Bona Syndrome are completely spontaneous, and the brain activity in the visual system is also spontaneous (since the subjects are blind, and therefore the visual brain areas do not receive sensory input from the outside world), the study of this syndrome provided the research team led by Dr. Avital Hachmi - a former research student in his group of Prof. Malach and currently a post-doctoral researcher at "University College London" (UCL) - a rare opportunity to examine the relationship between spontaneous brain activity and spontaneous behavior.

To test whether these spontaneous waves are responsible for Charles Bona syndrome, the researchers located five subjects who had lost their sight, but periodically experienced clear visual hallucinations - in their mind's eye. The researchers performed functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) on these subjects during the visual hallucinations and while they described in detail the content of their visions. The scientists then created videos based on the verbal description of those hallucinations and presented them inside the MRI device to the control group - people whose vision was normal. Another control group was of blind people who do not experience hallucinations; The researchers asked these subjects to imagine these and other items while inside the MRI machine.

The same visual brain areas were activated in the blind, sighted and imaginal

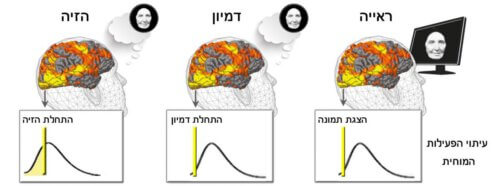

The scientists found that the same visual brain areas were activated in the three groups - the hallucinating, seeing and imagining group. However, there was a significant difference between the groups in the timing of the neural activity: while, as expected, in the sighted people and the imagining blind, the neural activity in the visual areas occurred in response to vision or the imagination task - in people with Charles Bona syndrome something else happened: the neural activity preceded the moment of the hallucination. In fact, the researchers clearly saw how a slow wave of activity - most likely a spontaneous wave of rest - gradually increased, and only then did the brains of Charles Bona's subjects get injured. In other words, the hallucination does not arise as a result of external activation (such as sensory input in the case of vision, or instruction in the case of imagination), but as a result of those slow waves that are spontaneously generated in the visual areas of the brain. "Our research clearly shows that the same vision system works both when we see the outside world and when we imagine, hallucinate - and probably also dream," says Prof. Malach. "The research illustrates the creative power of vision and the importance of spontaneous resting waves in the brain's ability for spontaneous and creative behavior."

Besides the importance of the scientific findings, Dr. Hachmi also wants to raise awareness of the existence of this syndrome, which causes great anxiety among those who are dealing with it. "Often, people with Charles Bona syndrome do not tell their doctor or their families about it. It is important that these people understand that this is a completely normal phenomenon - although their eyes no longer transmit information to the brain, the visual system in their brain is normal and continues to work. These hallucinations are the evidence of that."

Also participating in the study were Dr. Mittal Wilf, a former research student in Prof. Malach's laboratory, Dr. Boris Rusin from the ophthalmology departments of the Hadassah University Medical Center and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Prof. Marilyn Behrman from Carnegie Mellon University.

More on the subject on the science website: