I was recently asked to deliver a lecture at Tel Aviv University on the future of transportation, and I immediately began to hesitate. What to talk about? Driverless vehicles? Drones and flying cars? I chose to focus on the past, a similar period of rapid change

I was recently asked to deliver a lecture at Tel Aviv University on the future of transportation, and I immediately began to hesitate. What to talk about? Driverless vehicles? Drones and flying cars? Or maybe sail to the regions that tickle more the fans of science fiction, and run wild with ideas for genetic engineering of half-robot-half-horse-half-bat?

In the end I actually decided to go back in history to a time when transportation changed abruptly, and that huge change carries lessons for the future as well. The future of transportation, and the future in general.

A hundred years ago, the streets belonged to pedestrians. Then they were kidnapped from them, under the auspices of technology, progress and the car companies. Today we no longer even see anything strange in the fact that up to thirty percent of the city's area is dedicated to vehicles, and that the city's residents are not allowed to cross the road except at well-defined places and times - or risk death or, God forbid, a fine.

The story I will tell today comes to shed light on that period in history, in which one worldview was replaced by another, and an entire generation was forced to reshape the way it thinks about its way of living in cities.

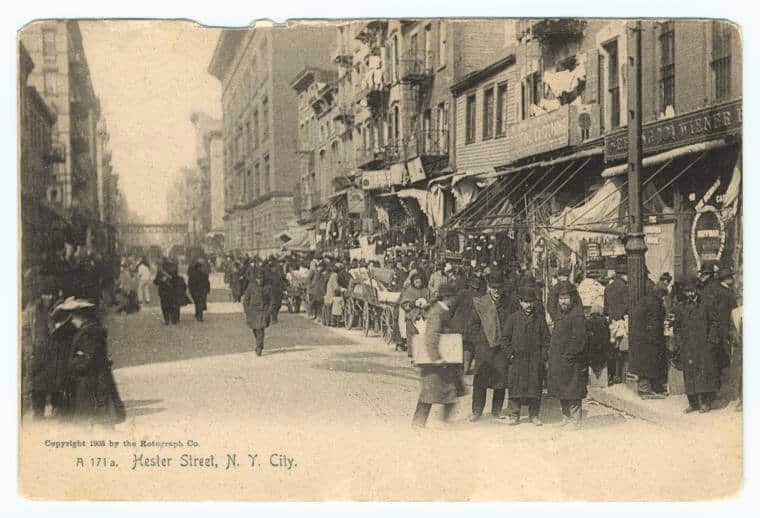

The debts of the cities at the beginning of the XNUMXth century looked very different from those we are familiar with today. In photos from that time you can see the 'road' in the center of the street, but it was not reserved for cars only. It was full of pedestrians who took for granted their right to cross it or walk along it[1]. Beside them you could find peddlers with carts, horse-drawn carriages, a small number of motorized vehicles and children playing football and catch among all these.

This state of affairs had to change following the increased penetration of motorized vehicles - cars, in short - onto the roads. A car, in general, is faster, bigger and heavier than the average wagon. It is not surprising to find that as more cars hit the roads, the number of fatal road accidents increased. Actually, it didn't grow: it exploded upwards. In just one decade - from 1910 to around 1920 - the number of fatal road accidents jumped tenfold[2].

As you can guess, the public did not take kindly to the matter. Private cars were still a type of amusement reserved only for the rich, and the rest of the common mortals were willing to tolerate them only up to a certain limit. That limit was at the point where the toys of the top decile started killing their children on the roads. The courts sided with the middle class at the time, relying on the rule of thumb that the heavier vehicle was responsible for the accident. This meant that a car driver could find himself on trial for manslaughter, just because he failed to brake when a child suddenly jumped out from under his wheels.

Vehicle manufacturers and sellers began to understand that they had to change the existing laws, along with the public mindset, if they wanted to increase sales. The first shot was fired in 1912, in Kansas City, where the legislators decided to prohibit pedestrians from crossing the roads except in well-defined places. The decision was received, as you can imagine, with disdain on the part of the residents and on the part of the journalists who covered it. After all, it was clear that the cities belonged to the humans. Why should the movement of the city's two-legged residents be criticized, instead of further restricting the movement of vehicles? [3]

For us, a hundred years after the fact, the answer is easy to understand. We know that without cars we would not be able to get from one end of the city to the other. The private cars and public transportation allow us to live on one side of the city - and work on the other side. Without trucks, which bring supplies and resources from all over the country, we would not be able to live comfortably in the city. Transportation is one of the factors that promote the economy to the greatest extent. Today's metropolises are built around roads for a good reason: they are the arteries through which the city's gasoline-rich blood flows.

All this is well known to us today. But a hundred years ago, no one was sure what the future of motorized vehicles would look like, especially within the city. You can think of modern drones as a comparison. Many are sure that in a decade we will already see a branch of commerce carried out using tens-of-thousands of drones above the roofs of houses. Unfortunately, the drones used for deliveries today make an unpleasant noise. Think how you would react if the municipality of Tel Aviv informed the residents that they must add a double layer of insulation to the windows of the houses, so that the drones moving above would not disturb their rest. Most likely the reaction was accompanied by a curse or two, or even - with a shudder - the opening of a petition. You would see no reason for placing the responsibility for silence on you, instead of it falling on the manufacturers and pilots of the drones.

The residents of the cities felt the same way when they saw the first laws against the right to walk freely in the street. And not only them, but also the judges, policemen and juries. Everyone was still fixated on the same strange notion that the city 'belongs' to the pedestrians who live in it, and not to the vehicles on the roads.

It was clear that the culture itself needed to be changed - a process that could require many generations. The car manufacturers were determined to implement it in just one generation.

How did they do that?

The industrialists appealed directly to the public's heart in three ways: ease, patronage and shame.

Industrialists, it must be remembered, had money. Money can make life much easier, and that was exactly the use it was intended for. The National Automobile Chamber of Commerce has launched a completely free service for journalists that has made their jobs much easier. The journalists were invited to inquire with the bureau about every case of a car accident - and in a short time they would receive a complete article that could have been printed the very next day. Journalists have ethics, of course, but they also have deadlines. Hard-pressed journalists often chose to rely on the Chamber of Commerce—and the result was that the auto industry dictated the tone of press coverage. You can guess who was blamed for the accident - the pedestrian or the car driver - in those articles.

The second way was through sponsoring campaigns against walking on the road. Schools hosted lecturers who warned the children not to step off the sidewalk lest they get run over, and countless activities illustrated to the children the danger that awaited them on the road.

Last but not least, the industry focused on shaming those citizens who refused to follow the law. Shaming, as the phenomenon is called nowadays. Advertisements in newspapers and posters on the walls presented the crossers as fools with a suicidal urge. Police officers were encouraged to shout loudly at pedestrians who did not cross the road properly, and clowns were hired to pretend in parades that they were run over by cars. In short, crossing the road illegally has become much worse than just "illegal". She became ridiculous.

It was already clear to the children of the next generation: roads are only crossed at crosswalks. For them, that's how things have always been. The social change is over and done with.

Throughout the story I presented the automobile industry as the great villains: those who initiated a comprehensive social and cultural change, while shaming and hurting thousands of people. The truth, naturally, is more complex. The Western world needed the motorized vehicles to jumpstart the economy - the same economy that ultimately improved everyone's lives. The vehicles would reach the roads anyway. The only question is when, and what price they would have exacted in human life, if the car manufacturers had not helped to engineer the public consciousness. Yes, children in Jesus - but their lives were saved. Yes, there was social engineering - but it was needed to prepare the ground for the new world.

All in all, sounds like a good deal to me.

The really important thing to understand in the story is that perceptions can change dramatically in just a decade or two. Sometimes this happens with a deliberate push from the capitalists. Sometimes from the government. Sometimes organically, from the people themselves, as happened (probably) with the fall of the Soviet Union. Things that seem obvious to us - that the road is ours - can change very quickly, to the point that our children will not understand at all that it is possible otherwise.

We are currently in a time of great transformation, which touches all areas of our lives. Our great-grandfather gave up thirty percent of the city, and received the modern world in return. What will we give up, what will we gain - and how will we ensure that our children and grandchildren even know about what we sacrificed?

The answers to all of these, as usual - in the future.

Oh, and also in my lecture at Tel Aviv University.

[1] https://www.history101.nyc/new-york-city-from-1900-to-1904

[2] https://www.vox.com/2015/1/15/7551873/jaywalking-history

[3] https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2014/11/jaywalkers-and-jayhawkers-pedestrian.html

More of the topic in Hayadan:

- Time travelers: 100 years since the death of Jules Verne: the future is here

- A senior scientist at Intel: "The car of the future does not require a huge IT investment to enable smart transportation"

- Future shock - 30 years later. Interview with Alvin Toffler

- Even without flying cars, the real future is much more interesting than the one predicted in the movie "Back to the Future 2"Introduction - predicting the next hundred years, from the book "The Physics of the Future" by Michio Kaku