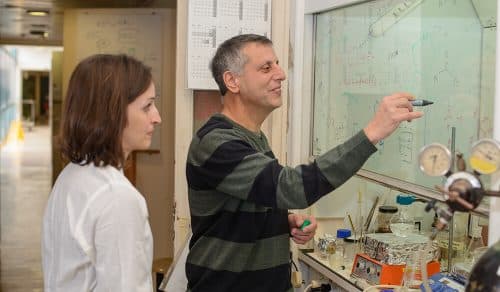

Prof. Dan Toufik from the Weizmann Institute of Science, who was killed in a climbing accident, was one of the senior researchers in the field of the development of artificial proteins and the study of the evolution of proteins

By Yahal Atzmon, Davidson Institute

Prof. Dan Tofik from the Weizmann Institute of Science was killed in an accident while climbing mountains in Croatia. Toufik, 66 years old, was a world-renowned researcher in the field of biochemistry and a pioneer in the study of the evolution of proteins. He was also the vice-chairman of the scientific council of the Weizmann Institute.

late start

Dan Tawfik was born in Jerusalem in 1955, and from a very young age he showed an interest in science, especially chemistry. "I did my first experiments even before the bar mitzvah," he said in a video produced on the occasion of his winning the AMT award for 2020. After he was released from permanent service in the IDF with the rank of major, he began studying at the Hebrew University for a bachelor's degree in chemistry and biochemistry, but interrupted The studies to work in the family construction company with his father and brother. He finished his bachelor's degree at a relatively late age, 33, and then went on to a master's degree in biotechnology at the Hebrew University. The next stop was the Weizmann Institute of Science, where he studied for a doctorate under the guidance of Michael Sela and Zelig Ashhar, and researched the use of antibodies against certain proteins. In 1995 he received a doctor's degree and went on to do post-doctoral training at the University of Cambridge in the UK. He was then appointed a faculty member. In 2001 he returned to Israel and joined as a researcher the Department of Biochemistry at the Weizmann Institute of Science, which is now called the Department of Biomolecular Sciences.

A short video about Dan Toufik on the occasion of receiving the AMT award, 2020:

Proteins that do not exist in nature

Tawfik's research deals with the evolution of proteins, and especially the evolution of enzymes, proteins that serve as catalysts for chemical reactions. Enzymes function in many cases as a kind of "biological machines" that maintain various life processes, from breaking down food in the intestines to replicating DNA in preparation for cell division. Without these catalysts, life as we know it could not exist.

In his first years at the Weizmann Institute, Toufik's research dealt with ways to develop artificial enzymes that would accelerate chemical processes that do not occur in nature. In an article in the journal Nature In 2008, Toufik and his partners, David Baker (Baker) from the University of Washington in Seattle, Orly Dym (Dym) and Shira Albeck (Albeck) from the Department of Structural Biology at the Weizmann Institute of Science, described the production of enzymes that catalyze the chemical reaction known as "Kemp elimination". They chose a reaction that in nature does not have enzymes that catalyze it, and with the help of computer programs they designed an "active site" in an enzyme that could catalyze it and a protein structure that could hold such a site. After that, they produced the proteins they designed in the laboratory and tested their effectiveness in speeding up the reaction. The new enzymes did have the desired activity, but did not show the efficiency of natural enzymes. To improve their effectiveness, the researchers subjected them to "evolution in a test tube": they introduced mutations in the genetic sequence responsible for the production of the artificial protein, thus causing small changes in the structure of the enzyme. By this method they obtained many versions of the artificial enzymes, each one slightly different from the other. From these they selected the most efficient enzymes in speeding up the reaction, and repeated the process over and over again. After seven cycles of in vitro evolution, the team had eight new enzymes, which caused the chemical reaction to occur at a million times faster rate than the same reaction without a catalyst.

The "evolution in vitro" method was also used In a study published in 2011 in Nature Chemical Biology, in which Tofik, together with his partner Yoel Sussman (Sussman) from the Department of Structural Biology at the Weizmann Institute of Science and with research colleague Moshe Goldsmith (Goldsmith), developed an enzyme that efficiently breaks down nerve gas. The enzyme is able to break down the gas inside the body of a living being, even before the gas is sufficient to damage the functioning of the nervous system. In this study, the in vitro evolution began with an existing enzyme, PON1, found naturally in the human body. PON1 accelerates decomposition processes of oxidation products of lipids that accumulate on the walls of blood vessels, thus helping to prevent arteriosclerosis. In addition to this activity, the PON1 enzyme also has a natural ability to catalyze the decomposition of nerve gas, but with a very low efficiency that does not allow it to be used as a defense against the gas. Using the methods of in vitro evolution, and causing mutations in the genetic sequence responsible for the production of the enzyme, the researchers were able to develop artificial enzymes that break down the nerve gas with high efficiency. In experiments in the laboratories of the United States Army, the researchers showed that the enzymes provide complete protection to animals if they are given as a preventive treatment before exposure to the nerve gas.

How were the first proteins formed?

After researching possibilities for the development of artificial enzymes, which would change the future of medicine, industry and research, Toufik turned to investigate the past. In an attempt to answer the question of how the first proteins were formed Tawfik's group investigated the possibility that modern proteins, which have a more or less spherical shape, arose from the duplication and attachment of a short initial protein segment. They examined a protein consisting of five units that are similar to each other, and by examining the differences between them and using computerized methods, they were able to reconstruct a relatively small protein that could be the "ancestor" from which all the units in the modern protein evolved. When Toufik and his team artificially produced the same ancient protein and put it through rapid evolution processes in vitro, they were able to show that the short segments can connect to each other following changes in the protein sequence, and assemble a protein with a contemporary structure made up of five units. Monitoring the process allowed the researchers to glimpse the forces that affect the production of an intact primary protein, and the required balances between these forces.

The complexity of the modern enzymes, and their great sensitivity to changes in the genetic sequence, made Tofik wonder how this great complexity was created through gradual evolution and what the initial enzymes were. To shed light on these questions, Taufik's research group combined protein comparison and computerized protein design to identify segments which have remained relatively conserved during evolution. These are similar segments that appear in proteins of the same family in different living things, even if they are evolutionarily far from each other. Thus, based on protein sequences that exist today in nature, the researchers were able to conclude that the earliest sequence in the family of proteins they examined is a short segment in the form of a loop, which binds the ATP molecule, which serves as the energy currency in the cell. Computer design of short proteins containing the ancient sequence, and their production in the laboratory, showed that these proteins, which may represent the ancient enzymes, bind not only ATP, but also RNA and single-stranded DNA. "Our findings indicate the possibility that the first proteins were a kind of 'helpers' for DNA and RNA", Toufik said To the Weizmann Institute of Science website. "They were probably multifunctional and relatively simple, and with the progress of evolution they developed into enzymes with increasing efficiency and uniqueness."

The proteins, which may represent the ancient enzymes, bind not only ATP but also RNA and single-stranded DNA, and are capable of self-assembly and the creation of distinct compartments. Fluorescence microscope image of the liquid droplets formed in the presence of the short proteins Weitzman Institution of Science

Awards and achievements

Toufik won many awards for his scientific work. Among other things, he was awarded Weizmann Prize for exact sciences (2007), The Eli Horowitz Excellence Award On behalf of Teva (2013) andA.M.T. Award (2020)

Next to the scientific research itself, Tofik saw the training of students for research work as a central part of his job. "My greatest source of pride is not publications or awards, but my students, students and post-doctoral students," said Toufik. "I managed to instill in them the love of science and specifically the love of enzymes and evolution. Today there are over fifteen of my former students who are professors all over the world. It is a tremendous source of satisfaction that I contributed to educating a generation of scientists."

Dan Toufik's lecture "Evolution, from the beginning of life and soon nowadays", Weizmann Institute of Science, 2016:

More of the topic in Hayadan: